- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

The Folk Of The Air Page 23

The Folk Of The Air Read online

Page 23

Julie said, “Please, will you try again? I’ll help you.”

“You help me?” Sia’s answer came so briskly and decisively that Farrell believed forever that she had had it ready before Micah Willows ever knocked on her door. “Child, no one can help me, no one except Briseis, and she can only do what she can do, You are incredibly stupid and selfish—and very brave—and you should go home now, this minute. For some things there is no help, you just go home.”

Julie’s voice trembled slightly when she replied, but her words were quick and clear. “You said that most people have at least a little magic. Mine comes from my grandmother, if I have any. She was born on an island called Hachijojima and she never learned English, but I spoke Japanese with her when I was small. I didn’t know it was Japanese, it was just the way Grandma and I talked. I remember she used to drive my parents crazy, because she’d tell me really scary stories about the different kinds of ghosts—shirei and muen-botoke and the hungry ghosts, the gaki. And ikiryo, they’re the worst, they’re the spirits of the living, and you can send them out to kill people if you’re wicked enough. I loved the ikiryo stories. They gave me such great nightmares.”

Sia was nodding, a drowsy old woman before a guttering fir. “And the goddesses—Marishiten, Sengen of Fujiyama. Did she tell you about Sengen, your grandmother?”

“Ko-no-hana-saku-ya-hime,” Julie chanted softly. “She said it meant that Sengen was radiant, like the flowers of the trees. And Yuki-Onna, the Lady of the Snow. I thought she was wonderful, even if she was Death.” She paused, but Sia said nothing, and Julie took a deep breath and added, “And Kannon. Especially Kannon.”

“Kuan-Yin,” Sia murmured. “Avalokitesvara. Elevenfaced, horse-headed, thousand-handed, Kannon the Merciful.”

“Yes,” Julie said. Briseis plopped her heavy head on Farrell’s knee, and he petted her, taking a sad, spiteful comfort in her need of him. Julie said, “I don’t remember this at all, any of it, but somehow my grandmother consecrated me to Kannon. A little private ceremony, just the two of us. My father walked in on it, and I guess he hit the roof. I don’t know. I couldn’t have been more than five or six.”

The black flames had gone out almost completely; the only light in the shadow-choked room seemed to emanate from the angry masks and, strangely, from Micah Willows’ wracked and scarred face. Julie went on, “All I’m sure about is that I didn’t get to be with Grandma so much after that age. I lost all my Japanese pretty fast; and I lost Grandma too. She died when I was eight. She’s buried on Hachijojima.”

Two shadows nipped Farrell’s ankles at once with icy little teeth that left no marks. He flailed them away, but others were moving in, shapelessly aggressive as Julie’s Japanese ghosts. Sia asked “Did you ever wonder why she did that, joining you and Kannon?”

“I don’t know. Maybe she was hoping I’d be a Buddhist nun.”

Sia was shaking her head again before Julie had finished. “Your grandmother was very wise. She had no idea what gift to give you for your life in this country that was already snatching you away from her, but she knew that human beings everywhere need mercy most of all.” She turned to look down at Micah Willows for a long moment, then said something almost inaudible to him in Arabic. Farrell had no doubt that she was repeating her last few words, mercy most of all.

“Well,” she said. In one remarkable movement she stood up, clapped her hands to drive the shadows back, snapped, “Oh, just be quiet!” to the masks—who paid her no attention whatsoever—and turned solemnly around three times, like Briseis bedding down. Farrell and Julie gaped, and she laughed at them.

“No magic, no miracle,” she said. “Only an old person trying to get her doddering self balanced properly. What we are going to do now is absolutely insane and insanely dangerous, and I think we should all get our feet well under us.”

Julie said, “Joe, you’d better go. You don’t have to be here.”

“Piss off, Jewel,” he answered, hurt and furious. His voice silenced the masks briefly, and Julie touched him and said, “I’m sorry.”

“Understand me,” the old woman said, and her own hoarse voice was suddenly so terrible that the room cleared of shadows instantly and Farrell glimpsed the distant, blessed outlines of chairs and chess pieces. Sia said, “I am not doing this for either of you, or even really for him—them—nor out of vanity, as I told you before. I am doing this out of shame, because I knew what had happened the moment it happened, and I did nothing. I did not dare to leave my house. I could have called him here to me, but I feared being destroyed if I tried and failed to free him. So I have done nothing at all for two years, until tonight.”

Farrell was never sure whether he had actually voiced his mild protest before she cut him off savagely. “Of course it was my responsibility! My responsibility is to see that certain laws are kept, certain gates are only allowed to swing one way. However tired or weak or frightened I am, this is still what I am for. If you insist on trying to help me, you do it out of ignorance, because you cannot possibly imagine what you risk. But I do this out of shame.”

Julie asked, “Do you think Kannon will come? What should I do? How should I call her?”

“Never mind Kannon,” Sia said. “Try calling your grandmother.”

She meant what she had said about balance, ordering Julie and Farrell to brace themselves in the dark room as carefully as if it were a moving subway car. She even propped Micah Willows against the fireplace as best she could before she turned and said, “Well,” a second time. The three of them ranged themselves around Micah Willows, with Briseis trembling next to him and Sia keeping one hand in the dog’s neck fur. Micah Willows hugged Briseis’s leg, looked up at them all and said, “Fucking doomed. Prester John knows.” Nothing else happened for a long time.

The starlight came back first, to Farrell’s great joy. He had intended to watch very closely this time, to see whether it was truly bound up in Sia’s hair or emanated from somewhere outside the room. But when it was there, it was simply there, making the room float on its foundation, and Farrell too happy to do anything but whisper a welcome and hold Julie’s hand. The scent of flowers grew warmer around them as the light spread—plumeria, the gods smell like Hawaiian plumeria—making him think of Sengen, beautiful as blossoming trees. Micah Willows, or the king within him, began to moan softly again with inconceivably fearful anticipation, and Farrell had a moment to wonder, is this how it is for Egil Eyvindsson, each time? Far above them all, Sia’s face was rising like the moon: golden and weary, battered into human beauty by endless stoning. Farrell could not bear to look to her.

Then she said something in a language like soap bubbles that could only have meant, no, damn it, damn it to hell, and, as if some celestial wrecking crew had gone to work, jagged pieces of night came plunging through the walls and ceiling of the living room. What Aiffe and Nicholas Bonner together had failed to accomplish seemed to happen in seconds now, as the room ripped itself to pieces like a torn kite in a gale. But the solid old houses and libertine gardens of Scotia Street and the Avicenna lights below had disappeared as well, leaving nothing beyond the shattered suggestion of Sia’s home but a sky fanged with strange, hurrying stars and a darkness that was also moving and that went on forever, past any hope of morning. It was the only vision Farrell was ever to have of raw, random space, and he could not keep his feet under him. He crouched down among the tumbling stars, covered his eyes and vomited, thinking absurdly, I’ll never finish sanding that old Essex now, never get home to finish that.

In a detached way, he was aware that Julie was crying out, somewhere nearby, “Kannon! Sho-Kannon, ju-ichi-men Kannon! Senju Kannon, ba-to Kannon, nyo-i-rin Kannon! Oh, Kannon, please be, Kannon, please! Sho-Kannon, senju Kannon!” She went on and on like that, and Farrell wanted to tell her to shut up because she was giving him a headache. But just then the goddess Kannon came to them, so he never did.

Julie said later that she had simply stepped through a hole in space

, pulling the endless, meaningless night apart with a hundred of her five hundred pairs of arms and letting it close behind her, but not before Julie had glimpsed the bluegreen shores of heaven and the dragons. But to Farrell, it seemed that she came slowly from a long way off and that she entered that place where they were through the one of Sia’s masks that had never sprung to nasty life, but was somehow hanging in perfect serenity on no wall, over no fireplace. It was a Kabuki mask, white as plaster; and as Farrell watched, it began gradually to stream with Kannon, dissolving over and over to flow into her round brown face, her flowering arms, cloudy robes, and long amber eyes. Her appearance pulsed and surged constantly, bordering always on forms and sizes and sexes beyond Farrell’s imagining or containing. Farrell saw her bow slightly to Julie, saluting and acknowledging her. When she looked at him, he wiped his mouth weakly, ashamed that she should see him so, but Kannon smiled. Farrell wept—not then, but later—because Kannon’s smile allowed him to, as it allowed him to forgive himself for several quite terrible things.

He always insisted that he had heard them talking together, Kannon and Sia, in the soap-bubble language, and that he had understood every word.

—Old friend—.

—Old friend—.

—I cannot help him. I am too tired—.

—I will help him—.

—You are younger than I and more powerful. You have many worshipers, I have none—.

—Illusion. We do not exist—.

—Perhaps. But the child called you, and you came—.

—Of course. How not? I know her grandmother—.

—Yes. Thank you, old friend—.

But Sia swore that they had never spoken at all, that there could be no need for speech between them; and Julie drove him wild by describing how Kannon had leaned down to Micah Willows and touched his eyes, actually touched them, and how he blinked and said, “Julie,” in a voice she remembered, and promptly fainted. Farrell missed that part altogether, having realized that Ben was hanging far off in the night like Sia’s Kabuki mask, peering drowsily across unhealed space at the scene below. Then Kannon bowed again to Julie—who was too busy with the still-unconscious Micah Willows to notice—and bowed low to Sia like the Northern Lights, and went away with the starlight, and Ben came on down restored stairs and crossed the creaky living room floor to Sia. He put his arms around her and held her as tightly as he could.

Micah Willows opened his eyes and said, “Julie? Man, who are these people?” Farrell stood quietly where he was, listening to the first birds, and to the sprinklers coming on at the house next door, and thinking entirely about Kannon’s smile.

Chapter 16

The war was not optional. Nearly every knight of the League, saving only the combat master John Erne and the King, was expected to take part in it, though the degree of a fighter’s activity was for him alone to choose. Farrell knew only that he belonged on Simon Widefarer’s side and that he would do something humane and encouraging on the home front. He asked Simon whether making hero sandwiches and teaming with Hamid ibn Shanfara to improvise morale-boosting songs for the troops entitled a man to noncombatant status. Simon guaranteed nothing, but recommended climbing a tree.

The rules of the war were simple and very few. The tangly thirteen-acre island in the middle of Lake Vallejo—a bay and a county away from Havelock—had been ceded annually to the League for the past several years, thanks to a combination of friends in moderate power and a lack of tourist interest in the poison-oak-ridden area. For a week preceding their dawn-to-dusk occupancy, the defending side was permitted to swarm over the island, constructing a web of plywood barbicans and outworks, as well as varyingly symbolic entrenchments, deadfalls, and mantraps, all centering on a primitive fortress, little more than a stockade atop a mound of earth. It was this castle that Garth de Montfaucon’s forces would have to take to win the war.

Combat was conducted as in any tourney, with the outcome being determined largely by honor and eight floating referees, four from each side. In the one departure from ordinary League procedures, each party was allowed the use of a weapon customarily forbidden. Simon Widefarer chose the longbow, Garth the morgenstern. In practice, as William the Dubious pointed out, it always came down to swords; but Simon’s choice committed the invaders to helmets and serious body armor, despite the special blunted arrows. “That adds up fast, on a hot day. They never write about it, but plain exhaustion must have accounted for as many armored knights as anything else, in the old wars. Look for them to start dropping around two o’clock, three maybe.”

“Can we hold them off that long?”

William beamed a bit muzzily. They had been helping to work on the wooden castle all afternoon, aided by a siegeworthy stock of Mexican beer. “Easiest part of it. The thing is, Joe, the defenders always have the edge. There are only three good places to land on this whole island—there used to be more, but Garth spent all week one year bringing in these huge rocks, and he dropped them around so they ripped the bottom out of anything that tried to beach. It’ll take them till noon just to get a foothold, and they’ll lose a lot of men doing it. They’ve only got till sundown, and we can keep them away from the castle till late afternoon sometime, with any luck at all.”

“Nice house odds,” Farrell said. He thought of adding, except for Aiffe, but instead he asked, “You’re really looking forward to this, aren’t you?”

William the Dubious nodded earnestly. “This will be my fifth. I just think it’s a great outlet for so much bad stuff—all your aggressions, your violence, phony behavior, the whole thing of choosing sides, winning. I think all wars will have to be like that pretty soon, like ours. Nobody can afford the real ones anymore, but people still have to have them.” He caught himself, laughed self-consciously and added, “Okay, men have to have them. See, I’m trained.”

On the evening before the war, Farrell went with Hamid to a meeting at William’s house to discuss plans for the War of the Witch, as it was already being called. Simon Widefarer and most of his strongest fighters were there, arguing like football fans about tourneys past and storied feats of arms in shattering mêlées; and, like connoisseurs of rugs or high fashion, about techniques of shield work and innovations in longaxe combat. There was mulled wine and homebrewed mead, and conversation slipped back and forth across the border between daily speech and the silly, haunting Ivanhoe language.

Farrell fell asleep and was nudged awake by Hamid when the gathering broke up. Drowsily he asked, “How’d it come out? Do we have a game plan?”

“Best game plan in the world,” Hamid said. “Pound ‘em on the head, stay out of the poison oak, and run like hell when Aiffe shows up. One slick game plan.”

Farrell had come to the meeting in League dress—tights, tunic and a laced vest that Julie had made for him—like everyone else except Hamid, who had arrived directly from his post office job, wearing tan slacks, a white short-sleeved shirt, and—in spite of the heat—a narrow red tie, elegant as a serpent. Passers-by turned completely around to stare at them as they walked down through the sweetly smothering night. Hamid said, “I got to stop drinking that damn mead of William’s. You could fly model airplanes on it.”

“I understand he’s catering the war,” Farrell said. “You still think Aiffe’s going to show? Simon kept swearing she’d promised the Nine Dukes or somebody—”

“Man, I know she is!” Hamid stopped walking. “Simon was just trying to keep their minds off that battle roster Garth sent over. We got them outnumbered damn near two to one. You think old Garth didn’t notice? You think he’d ever let the odds stack up like that if he didn’t have a little game plan of his own?” His voice rose and softened into the singing mumble of the St. Whale saga. “Oh, it is going to be a one-woman extravaganza, live from Las Vegas, and when it’s over there won’t be any more wondering, any uncertainty about just who is the star around this League. And there is to be a death.”

They were two blocks further along before F

arrell could believe Hamid’s last words enough to repeat them. Hamid blinked. “Did I say that? I told you, I have got to lay off the mead—it throws me right into my bard routine, and I don’t even notice.” He was silent for another block, and then he said quietly, “No, that’s not true. It just happens like that once in a while, with bards.”

“A death,” Farrell said. “Whose death? How?”

But Hamid walked on, striding out faster than Farrell had ever seen him, making the red tie lick backwards over his shoulder. “The voice just came out with it, it does that. Pay it no mind.”

He did not speak again until they were nearing the Parnell corner where Farrell would turn off toward Julie’s house. Then he said thoughtfully, “Word has it that a certain mutual royal friend is no longer on the street. Glad to hear it,” but there was a questioning tilt at the end.

Farrell said, “He’s in the hospital, getting over malnutrition, kidney trouble, a spot of anemia, and a couple of those things you get from living out of dumpsters. Also, he’s way past time for his regular dental checkup, and he’s under what they call observation because he has real trouble remembering who and when he is. But he’s doing fine.”

“Well, I’m sorry I didn’t tell you the truth about him,” Hamid said. “I’ll be honest, I had my doubts as to how much you could take in.” He cut short Farrell’s indignant response. “Yeah, I know what you and I saw Aiffe do, but you got to understand, I have also seen more than a hundred intelligent people steadily denying something she pulled off right in front of their eyes. Unmaking it, you hear what I’m saying? Changing him, changing Micah, to fit the story, I saw them doing it. Man, he helped found and organize this whole damn League, and two weeks, three weeks, he was just another crazy black man, gone AWOL, gone native, the way they got this unfortunate tendency to do.” His voice was shaking as badly as the hand that gripped Farrell’s forearm, the enviable, expected grace of being in sudden shreds. “You ever want to see the real witchcraft, you watch people protecting their comfort, their beliefs. That’s where it is.”

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand Return

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

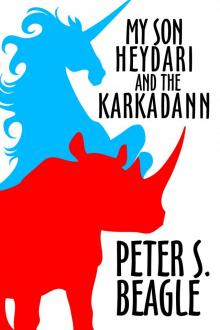

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

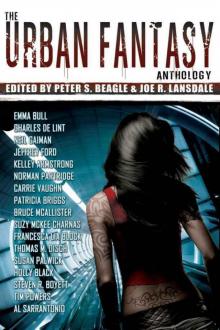

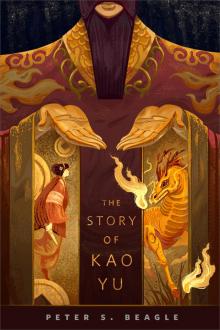

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

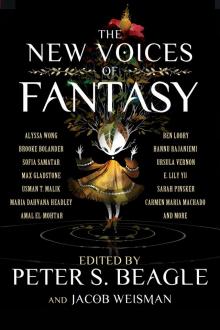

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

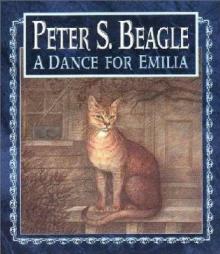

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song