- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

The Folk Of The Air Page 25

The Folk Of The Air Read online

Page 25

“Tantric sorcery. Sex magic. Really effective if you know what you’re doing, dynamite if it gets loose. Sort of like Leg-O’s—you can make all kinds of really unpleasant stuff with it. Sia said they’d be using that.”

“What else did she tell you?”

Ben shrugged, smiling wearily. “Hard to remember. I mean, she woke me up, dumped me out of bed, damn near dressed me, and shoved me into that van. She kept saying something terrible was going to happen, and I was to stay with you all day. And a pain in the ass it has been, I may add, trying to fight and watch over you at the same time. I haven’t been doing either one very well.”

Their voices sounded fragile and very far away to Farrell—spider-ghosts scurrying hand over hand up the dusty pillars of light. He told Ben about Hamid’s warning and the circumstances of it. “Is that what Sia was talking about? Look, just tell me.”

Ben did not answer for a while, long enough for Farrell to become aware that Julie’s mail shirt had chafed several raw places on his neck and shoulders. Ben said at last, “She’s not always right, you know. And sometimes when she is right, it’s not in any way you could have imagined. Who knows what Sia means by death?”

The first sending exploded into being as they were informing Simon Widefarer that Aiffe and Nicholas Bonner were on the island. It looked like a raw, bloody stomach with a crocodile’s head, and it flew at them on wings edged with tiny mouths. Ben, Farrell, and Simon screamed and fell to the ground, and the creature flashed stinking over them; wheeling back for another go, making the sound of sucking mud. It had ridiculously bright blue eyes.

Half of Simon’s forces had been drawn into the plywood castle by now; the remainder—Hamid among them—were either off scouting, skirmishing, or helping to shore up the fortress’s rickety outer walls, as Farrell and Ben had found Simon doing. The structure was actually a good deal more solid than it looked, a fact proved conclusively by the time the second and third monster—one half-toad, half-gamecock, the other something like a pulpy Nutcracker Suite mushroom with yellow human teeth and a snake’s tongue—were streaking and circling low above the castle. At that point, so many yelling knights of the League had jammed through the entranceway and the two sally-ports that the entire castle should have been as flat as a split milk carton; but the walls remained upright, conveniently for the sendings, who perched on them. More and more came banging into being: goat-legged viscera, fanged cacti, huge, houndfaced slugs, creatures like stuffed toys oozing sewage, creatures like tall skeletal birds with fire pulsing between their ribs. Without exception, they smelled of carnivores’ excrement; and they kept coming, inexhaustible nightmare hybrids, chattering like parakeets, snuffling like bears. They dive-bombed, those who fled; they swooped low to snap and jeer at hysterical knights rolling on the ground; they overran the red sundown, leaving just enough daylight to see them by. Aiffe’s children, Farrell thought, and thought that he laughed into the trampled brown grass.

Beside him, Ben grunted, “Fuck this,” and stood up, brushing sendings away from him like gnats. “Absolutely harmless,” he announced loudly. “Low-budget special effects, might as well be afraid of a slide show. Let’s get on with the war.” He walked briskly toward the castle, picking up a hammer and a handful of nails to work on the weakened frame. Farrell followed, shoving after him through hot clouds of hovering phantasms. He always swore that one of them lit on his shoulder for a moment, and that the stench lingered in the tunic ever afterward. He never wore the tunic again and finally burned it one night, years later, when he was drunk.

“She’s very good,” Ben said quietly. “If he hadn’t been pushing her a bit too hard, we’d have been in big trouble.”

“Those things aren’t real,” Farrell offered cautiously. Ben shook his head irritably, hammering in a corner support. “Not quite, not yet. They will be. Another month, another week. The least little bit overtrained, that’s all,” He might have been talking about a distance runner. “I certainly wonder what she’ll try now.”

The sendings kept at it a while longer, increasingly petulant rather than menacing, badgering Simon’s knights for attention as the men returned to the castle in shaky, shamefaced twos and threes. A veil was thickening between them and the day they had raided; and by the time Hamid ibn Shanfara drifted in, they had been reduced almost to misshapen pigeons cadging handouts around park benches. Abruptly they twitched out of existence all at once, as if a single switch had shut them down. The late light came back, turning shadows green and gold, showing a good hour yet to sunset. Ben said again, “Now what?”

“Ah, as to that,” Hamid murmured in his legend-voice. “As to that, perhaps someone espied two handsome children in the wood, not twenty minutes since, and perhaps one said to t’other, ‘Nay, but you’ll not do this thing, I forbid it, so.’ And meseems the little girl gave him the lie straight away, saying for answer, ‘Forbid yourself, turkey. This shit is boring, and I am about to lose the damn war, messing around like this and the sun going down. Behold and stand back, for I will get myself some real help right now.’ But t’other was wondrous wroth, and says he, ‘For your life, you dare not! This is nothing for you, this is more than you can yet hold, on my word, sweet sister, on my word.’ And it might be she laughed at him, and perhaps someone heard her say then, ‘You have no word, and I told you when I summoned you first that I can handle anything I can call. And so I can, Jack, with or without you, I got it down!’ And it is said that he railed further at her folly, but perhaps not. A bard must say only what he knows.” He bowed slightly to Ben and Farrell and began rewinding his turban, amazingly immaculate.

Simon Widefarer was inside the plywood castle, spacing his men thinly along the walls to meet the sunset attack. Farrell was startled to realize how greatly their numbers had been reduced; between losses in battle and a dozen suspicious injuries, Simon was captain only of some sixteen exhausted knights besides himself. At first, he would not part with even one when Ben and Farrell repeated Hamid’s tale to him and urged a scouting expedition. “Not if she were coming down on us with all of Charlemagne’s paladins. What use is the knowledge now?” But Ben pressed the need fiercely, and Simon finally yielded, saying, “Let him go then—” He pointed to Farrell. “—and him.” He indicated the Scots laird Crof Grant, plaided to the eyebrows and topped off by a bonnet like a Christmas fruitcake, sagging with red and green clan badges, erupting with plumes enough to reconstruct the whole ostrich. Simon said, “I cannot spare Egil Eyvindsson from the defense, but two such will leave us little weaker.” Farrell felt as if he had once again been chosen last at stickball.

Skulking through the brush with Crof Grant was a reasonably similar experience to the time Farrell had tried to smuggle a pool table out of a fourth-floor walk-up at midnight. In the first place, Grant’s costume refused entirely to skulk, but caught on anything that made a noise, including Farrell; in the second, the man himself never ceased to prattle, in a constant warm spatter of glottals and occlusives, of the countless Sassenach rogues fallen that day to his trusty claymore. Hushing him did no good at all, since he was talking louder than Farrell dared raise his own voice. He was in the middle of a singlehanded stand against three foes armed with morgensterns, armored in crushing youth—“Losh, laddie, gin ye add their years thegither, ye’d hae no mair than my ain”—when they came into a clearing and saw Garth’s men waiting silently for them.

To do Crof Grant justice, he said only, “Hoot-toot,” before he started running. Farrell lingered for a deadly instant, not out of surprise or paralysis, but because of the five men grouped close behind Aiffe where she stood with her father. At first glance there was little to tell them from the rest of Garth’s tattered forces, grim alike with weariness; but Farrell had seen the yellow-eyed man in Sia’s house, and he had understood Aiffe’s challenge to Nicholas Bonner. Oh, my lord, she does have it down. Then Aiffe saw him and laughed and pointed, and one of the strange knights bent a bow at him so fast that he never saw it happen. The arrow

sighed in his left ear, sinking itself out of sight in a juniper bush.

Farrell was running by then, half-crouched, hands guarding his face, struggling through blackberry, hemlock, and wild lilac, falling once and having to make sure that the lute was all right, and hearing himself making small noises like a garden hose or a steam radiator that has not been quite shut off. Away to one side, there was an immense crashing and stumbling that must surely be Crof Grant in flight, while behind him he heard only Aiffe’s whooping, shuddering laughter. But he knew who was pursuing him as clearly as he had suddenly known who they were: the real thing, genuine gunslingers out of the genuine Middle Ages, out of the Crusades, the Spanish Netherlands, the Wars of the Roses. Unpretentious, unwashed, unmerciful—the real thing, ready for bear. Lady Kannon, pity now. At that point, he dodged around one tree cheek-first into another and spun back to the first tree, slipping down against it, still reaching to shield the lute.

He lost color for a little while. When he could stand, three gray people were almost on him. The one closest might have been a pilgrim turned mercenary or a Norman invader of Sicily. Under a steel cap, he had a square, windburned face with flat cheekbones and tufty eyebrows, and his look was so peaceful and humorous as to be called insane. Farrell picked up a dead branch, watching with numb, patient curiosity as the man came on, noting equally the slight bend of the knee, the seemingly loose grip on the sword, and the flakes of dandruff in the pale eyebrows and mustache. The sword had a raw, winking notch near the tip, and the unbound pommel looked like an old brass doorknob. Farrell wondered whether the light reflected into his own face came from the setting sun of Avicenna or Palestine.

He held up his branch as the sword started back. It moved unnaturally slowly, the knight’s lips wrinkling with the same deliberation, his body setting itself for a sidearm blow. Then Crof Grant was trundling between them, grappling fearlessly for the sword and rumbling out, “Fye na, haud ye’er brand for sair shame. Tis a naked museecian, man—would ye harm a sleekit, cow’rin, tim’rous minstrel?” The dreadful bonnet was gone, and his white hair kept falling into his eyes. The knight growled very softly and stepped away from him, moving up on Farrell from another angle. Grant was after him again, partially interposing his slow, shrouded body, “Nay, I say ye shanna‘! I say haud! Dinna ye ken League rules, man?”

The sword melted into the side of his throat, and he slapped vaguely at the wound before he stumbled down. Color came back with his blood.

Farrell never remembered how he reached the castle; only that he was not followed, and that he was crying when he got there. Ben held him on his feet and almost literally translated his near-hysterical report to Simon Widefarer, but no one else, except Hamid, seemed to take any of it seriously. He was reassured on all sides that Crof Grant could not possibly be really dead, that metal swords were never allowed in League combat, and that neither captain would even consider enlisting new fighters, once a war was under way. As for Aiffe’s monstrous sendings, the minority willing to discuss them at all favored mass hallucinations brought on by uniform minor sunstrokes, such as had been happening all afternoon. Meanwhile there was a last stand to prepare for, and a serious need of heartening music. Hamid looked down at him from a teetery catwalk, saying nothing.

The attack came no more than twenty minutes before sunset. There was no attempt at surprise; rather, the surviving knights of Garth de Montfaucon’s party—still fewer than Simon’s forces, and looking even more spent—approached the castle boldly, stepping with a slow, menacing rhythm and chanting grim burdens to keep time. Garth himself swaggered in the lead, but Aiffe and Nicholas Bonner walked unobtrusively to one side in their anonymous squires’ dress, followed by the five men she had summoned to her. On the catwalk, Farrell said to Hamid, “That’s the one. Second on the left, the short guy.” He thought that Aiffe looked anxious and subdued. Hamid said without expression, “I don’t want him to be dead. I don’t want to predict anyone’s death.”

“He’s dead, all right,” Farrell said.

Garth drew his troops up before the outer wall and stood forward, calling, “Now stand well away, of your kindness, for we’d see none injured when the walls come down.” Farrell knew that a battering-ram entry was as much a tradition of League wars as ransoms and victory feasts, but no ram was visible among the attackers. Nevertheless, there were knights on the wall who began to back away.

“Steady all,” Simon shouted, “Give them no heed, but look to your bowstrings.”

Aiffe kissed both of her hands loudly and blew the kisses toward the castle, spreading her arms to wave them on their way. The inner and outer gates fell down flat, and Garth’s men swarmed in through the rising dust.

Simon Widefarer and his archers fired frantically into the first rush, dropping a few as they scrambled over the gates. After that there was no free play, even for the morgensterns, and no room for referees. The castle seethed and rocked like a subway car at rush hour; fighting knights were hurled apart, unable to find their combat again, or stumbled together straight through someone else’s mêlée, and were cut down by their comrades, as likely as not. For those who fell, there was a very real danger of being badly trampled, and Farrell and Hamid hauled several such as far out of range as they could. They were huddled in a rear corner, Farrell curled protectively around the lute, Hamid jauntily crosslegged, still taking notes aloud. The dust went up elegantly, orange and gray, poising just over the scene like the fighter’s breath.

“Here they are,” Hamid said softly, and Farrell looked up to see Aiffe’s five summonings passing through the ragged gateways, three abreast, two following singly, moving into the battle as delicately as cats stalking a birdbath. Farrell was fascinated to see how much like any costumed bank managers they looked, even knowing what he knew. Hamid said, “All more or less from the same time period. I make it one Norman, one Venetian free-lance, two early Crusaders, and I don’t know what your boy there is, except nasty.” They both stood up as he want on musing. “Wonder how she handled the shock factor. They look pretty cool, considering they surely had other plans for the afternoon.”

At the top of his lungs, Farrell shouted the first word that came to him. “Realies!” Hamid burst out laughing, but no one else paid the least attention. Farrell yelled, “Real swords, ringers, look out, they’ve got real swords!” The five men spread out, choosing their targets. The Venetian went for Simon Widefarer, and the one who had killed Crof Grant came straight toward Farrell and Hamid.

Hamid said, “Some day we got to talk about whether it was really necessary for you to do that.” The Norman caught William the Dubious with a side cut that doubled him over, then aimed a finishing blow meant to shatter his helmet. The man who had killed Crof Grant blocked Farrell’s view. He looked happy and zestful, as if he were meeting dear friends at the airport.

As the sword began to come up, Hamid chanted loudly, “Hate to talk about your mama, she’s a good old soul,” and danced away to Farrell’s left. The sword flickered involuntarily to follow him, and Farrell shoved the lute into the man’s face, knocking the steel cap sideways. Everything in him screamed against the idea of using the instrument as a weapon; but he thought about vain, rumbling, ridiculous Crof Grant trying to protect him, and he hit his killer in the head with the lute as hard as he could. The beautiful elliptical back caved in as the man wandered to his knees. Farrell hit the man a second time before Hamid yanked him away from there.

The battle had traveled at least two stops beyond chaos. Whether or not Aiffe had ever understood that her summonings could not be controlled to the point of pretending to kill, that pretending was not in them, it was clear that she had never considered their effect on Garth’s own men. Some of his mightiest fighters were plainly distracted with fear of them and seemed positively grateful to be taken early out of the action. Others were astonishingly outraged, turning on their terrifying allies to defend Simon Widefarer’s knights from any assaults but their own. Aiffe’s summonings struck back

without hesitation, and the real swords drew real blood, leaving men on both sides staggering halfblind with scalp wounds, useless sword arms and badly slashed legs from attempts at hamstringing. Farrell himself took a blow across the chest that drove Julie’s chain mail deep into his flesh, leaving the ring-pattern visible—and breathing an activity not to be engaged in lightly—for more than a week. The five of them could kill us all.

Later, he and Hamid agreed that John Erne would have been proud of his combat students, and that they in turn owed him their lives, though most of them never knew it. Impossibly overmatched as they were against twelfth-century professionals, the moves and defenses he had taught them saved them at least from being instantly hacked down where they stood. Farrell saw a plump boy, his straggly blond mustache thick with blood, fake the Norman off-balance with hip movements as slick as a basketball player’s; and he saw one of the Crusaders launch an overhead cut at the Ronin Benkei which would have split a wooden shield and the body behind it as well. But the Ronin Benkei sidestepped and brought his round steel shield up so hard that it slammed the sword out of the Crusader’s hand, sending it tumbling all the way to the flattened inner gate. He never did get it back, but made wicked do with a dagger after that. Farrell was always sure that Garth de Montfaucon kept the sword.

There was an immense shouting going on somewhere now, carving a name over and over into the dusty twilight: “Eyvindsson! Eyvindsson!” Ben was standing near the gate, roaring and swinging an axe as long as one of the great twohanded swords. His face was the way Farrell had seen it once before, blazing pale, bent with another man’s rage out of time and with a delight in rage for which Farrell knew a few dead words. The longaxe whipped around his head, making a sound like a big animal panting, and Ben howled the name as if in awful mourning for himself. “Eyvindsson! Eyvindsson! Eyvindsson!”

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand Return

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

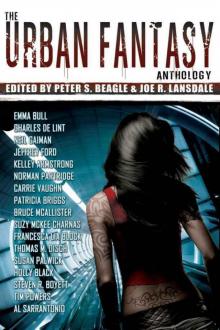

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song