- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

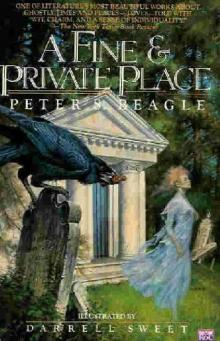

A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Read online

A Fine and Private Place

Peter S Beagle

Now available in a handsome trade paperback edition, this timeless classic of a romance between two ghosts who must fight to remain cognizant of what life and love once were--and still are--is a love story that transcends all love stories and a ghost story that transcends all ghost stories. Funny and heartwarming, it's perfect for young readers and adults alike.

A Fine and Private Place

Peter S. Beagle

This first one

for my parents, Simon and Rebecca,

and for my brother Daniel,

and, as it must be,

for Edwin Peterson

The grave's a fine and private place,

But none, I think, do there embrace.

-Andrew Marvell

"To His Coy Mistress"

Chapter 1

The baloney weighed the raven down, and the shopkeeper almost caught him as he whisked out the delicatessen door. Frantically he beat his wings to gain altitude, looking like a small black electric fan. An updraft caught him and threw him into the sky. He circled twice, to get his bearings, and began to fly north.

Below, the shopkeeper stood with his hands on his hips, looking up at the diminishing cinder in the sky. Presently he shrugged and went back into his delicatessen. He was not without philosophy, this shopkeeper, and he knew that if a raven comes into your delicatessen and steals a whole baloney it is either an act of God or it isn't, and in either case there isn't very much you can do about it.

The raven flew lazily over New York, letting the early sun warm his feathers. A water truck waddled along Jerome Avenue, leaving the street dark and glittering behind it. A few taxicabs cruised around Fordham like well-fed sharks. Two couples came out of the subway and walked slowly, the girls leaning against the men. The raven flew on.

It had been a hot night, and the raven saw people waking on the roofs of the city. The gray rats that come out just before dawn were all back in their cellars because the cats were out, stepping along the curbs. The morning pigeons had scattered to the rooftops and window ledges when the cats came, which the raven thought was a pity. He could have done with a few less pigeons.

The usual early fog was over Yorkchester, and the raven dropped under it. Yorkchester had been built largely by an insurance company, and it looked like one pink brick building reflected in a hundred mirrors. The houses of Yorkchester were all fourteen stories tall, and they all had stucco sailors playing accordions over the front entrances. The rear entrances all had sailors playing mandolins. The sailors were all left-handed, and they had stucco pom-poms on their hats. There was a shopping center, and there were three movie theaters, and there was a small square park.

There was also a cemetery, and it was over this that the raven swooped. It was a very large cemetery, about half the size of Central Park, and thick with trees. It was laid out carefully, with winding streets named Fairview Avenue, and Central Avenue, and Oakland Avenue, and Larch Street, and Chestnut Street, and Elm Street. One street led to the Italian section of the cemetery, another to the German section, a third to the Polish, and so on, for the Yorkchester Cemetery was nonsectarian but nervous.

The raven had come in the back way, and so he flew down Central Avenue, holding the baloney in his claws. The stretch of more or less simple headstones gradually began to give way to Old Rugged Crosses; the crosses in turn gave way to angels, the angels to weeping angels, and these finally to mausoleums. They reared like icy watchdogs over the family plots and said, "Look! Something of importance has left the world," to one another. They were aggressively Greek, with white marble pillars and domed roofs. They might not have looked Greek to a Greek, but they looked Greek to Yorkchester.

One mausoleum was set away from the others by a short path. It was an old building, not as big as some of the others, nor as white. Its pillars were cracked and chipped at their bases, and the glass was gone from one of the barred grates over the front door. But the two heavy door-rings were held in the mouths of two lions, and if you looked through the window in front you could see the stained-glass angel on the back wall.

The front door itself was open, and on the steps there sat a small man in slippers. He waved at the raven as the bird swept down, and said, "Good morning, good morning," as he landed in front of him. The raven dropped the baloney, and the small man reached forward eagerly and picked it up. "A whole baloney!" he said. "Thank you very much."

The raven was puffing for breath a little and he looked at the small man rather bitterly. "Corn flakes weren't good enough," he said hoarsely. "Bernard Baruch eats corn flakes, but you have to have baloney."

"Did you have trouble bringing it?" asked the small man, whose name was Jonathan Rebeck.

"Damn near ruptured myself." The raven grunted.

"Birds don't get ruptured," said Mr. Rebeck a little uncertainly.

"Hell of an ornithologist you'd make."

Mr. Rebeck began to eat the baloney. "Delicious," he said presently. "Very tender. Won't you have some?"

"Don't mind," said the raven. He accepted a piece of baloney from Mr. Rebeck's fingers.

"Is it nice out?" Mr. Rebeck asked after a moment.

"Nice," the raven said. "Blue sky, shining sun. The world stinks with summer."

Mr. Rebeck smiled a little. "Don't you like summer?"

The raven lifted his wings slightly. "Why should I? It's all right."

"I like summer," Mr. Rebeck said. He took a bite of his baloney and said with his mouth full, "It's the only season you can taste when you breathe."

"Jesus," the raven said. "Not so early in the morning. Incidentally, you better get rid of all those old paper bags. I can see them from outside."

"I'll drop them in the wastebasket in the men's room," Mr. Rebeck said.

"No you won't. I'll fly them out. People start wondering, you know. They see paper bags in a cemetery, they don't think the Girl Scouts are having a picnic. Besides, you hang around there too much. They're going to start remembering you."

"I like it," Mr. Rebeck said. "I'm very fond of that lavatory. I wash my clothes there." He locked his hands around his knees. "You know, people say the world is run by materialists and machines. It isn't, though. New York isn't, anyway. A city that would put a men's room in a cemetery is a city of poets." He liked the phrase. "A city of poets," he said again.

"It's for the children," the raven said. "The mothers bring the kids to see the graves of their great-uncles. The mothers cry and put flowers on the grave. The kids gotta go. Sooner or later. So they put in a big can. What else could they do?"

Mr. Rebeck laughed. "You never change," he said to the raven.

"How can I? You've changed, though. Nineteen years ago you'd have been sloppily thankful for a pretzel. Now you want me to bring you steaks. Give me another hunk of baloney."

Mr. Rebeck gave him one. "I still think you could do it. A small steak doesn't weigh so much."

"It does," said the raven, "when there's a cop hanging on one end of it. I damn near didn't get off the ground today. Besides, all the butchers on this last frontier of civilization know me now. I'm going to have to start raiding Washington Heights pretty soon. Another twenty years, if we live that long, I'll have to ferry it across from Jersey."

"You don't have to bring me food, you know," Mr. Rebeck said. He felt a little hurt, and oddly guilty. It was such a small raven, after all. "I can manage myself."

"Balls," said the raven. "You'd panic as soon as you got outside the gate. And the city's changed a lot in nineteen years."

"Pretty much?"

"Very damn much."

"Oh," said Mr. Rebeck. He put the rest of the baloney aside, wrapping it

carefully. "Do you mind," he said hesitantly, "bringing me food? I mean, is it inconvenient?" He felt silly asking, but he did want to know.

The raven stared at him out of eyes like frozen gold. "Once a year," he said hoarsely. "Once a year you get worried. You start wondering how come the airborne Gristede's. You ask yourself, What's he getting out of it? You say, 'Nothing for nothing. Nobody does anybody any favors.'"

"That isn't so," Mr. Rebeck said. "That isn't so at all."

"Ha," said the raven. "All right. Your conscience starts to bother you. Your cold cuts don't taste right." He looked straight at Mr. Rebeck. "Of course it's a trouble. Of course it's inconvenient. You're damn right it's out of my way. Feel better? Any other questions?"

"Yes," said Mr. Rebeck. "Why do you do it, then?"

The raven made a dive at a hurrying caterpillar and missed. He spoke slowly, without looking at Mr. Rebeck. "There are people," he said, "who give, and there are people who take. There are people who create, people who destroy, and people who don't do anything and drive the other two kinds crazy. It's born in you, whether you give or take, and that's the way you are. Ravens bring things to people. We're like that. It's our nature. We don't like it. We'd much rather be eagles, or swans, or even one of those moronic robins, but we're ravens and there you are. Ravens don't feel right without somebody to bring things to, and when we do find somebody we realize what a silly business it was in the first place." He made a sound between a chuckle and a cough. "Ravens are pretty neurotic birds. We're closer to people than any other bird, and we're bound to them all our lives, but we don't have to like them. You think we brought Elijah food because we liked him? He was an old man with a dirty beard."

He fell silent, scratching aimlessly in the dust with his beak. Mr. Rebeck said nothing. Presently he reached out a tentative hand to smooth the raven's plumage.

"Don't do that," said the bird.

"I'm sorry."

"It makes me nervous."

"I'm sorry," Mr. Rebeck said again. He stared out over the neat family plots with their mossy headstones. "I hope some more people come soon," he said. "It gets lonesome in the summer."

"You wanted company," the bird said, "you should have joined the Y."

"I do have company, most of the time," Mr. Rebeck said. "But they forget so soon, and so easily. It's best when they've just arrived." He got up and leaned against a pillar. "Sometimes I think I'm dead," he said. The raven made a sputtering sound of derision. "I do. I forget things too. The sun shines in my eyes sometimes and I don't even notice it. Once I sat with an old man, and we tried to remember how pistachio nuts tasted, and neither of us could."

"I'll bring you some," the raven said. "There's a candy store near Tremont that sells them. It's a bookie joint too."

"That would be nice," Mr. Rebeck said. He turned to look at the stained-glass angel.

"They accept me more easily now," he said with his back to the raven. "They used to be dreadfully frightened. Now we sit and talk and play games, and I think, Maybe now, maybe this time, maybe really. Then I ask them, and they say no."

"They'd know," the raven said.

"Yes," Mr. Rebeck said, turning back, "but if life is the only distinction between the living and the dead—I don't think I'm alive. Not really."

"You're alive," the raven said. "You hide behind gravestones, but it follows you. You ran away from it nineteen years ago, and it follows you like a skip-tracer." He cackled softly. "Life must love you very much."

"I don't want to be loved," Mr. Rebeck cried. "It's a burden on me."

"Well, that's your affair," the raven said. "I got my own problems." His black wings beat in a small thunder. "I gotta get moving. Let's have the bags and stuff."

Mr. Rebeck went into the mausoleum and came out a few moments later with five empty paper bags and an empty milk container. The raven took the bags in his claws and waved aside the container. "I'll pick that up later. Carry it now and I'll have to walk home." He sprang into the air and flapped slowly away over Central Avenue.

"Good-by," Mr. Rebeck called after him.

"See you," the raven croaked and disappeared behind a huge elm. Mr. Rebeck stretched himself, sat down again on the steps, and watched the sun climb. He felt a bit disconcerted. Usually, the raven brought him food twice a day, they exchanged some backchat, and that was that. Sometimes they didn't even talk. I don't know that bird at all, he thought, and it's been all these years. I know ghosts better than I know that small bird. He drew his knees up to his chin and thought about that. It was a new thought, and Mr. Rebeck treasured new thoughts. He hadn't had too many lately, and he knew it was his fault. The cemetery wasn't conducive to new thoughts; the environment wasn't right. It was a place for counting over the old, stored thoughts, stroking them lovingly and carefully, as if they were fine glassware, wondering if they could be thought any other way, and knowing deeply and securely that this way was the best. So he examined the new thought closely but gingerly, stood close to it to get the details and then away from it for perspective; he stretched it, thinned it, patted it into different shapes, gradually molding it to fit the contours of his mind.

A rush of wings made him look up. The raven was circling ten or fifteen feet above him, calling to him. "Forget something?" Mr. Rebeck called up to him.

"Saw something on the way out," the bird said. "There's a funeral procession coming in the front gate—not a very big one, but it's coming this way. You better either hide in a hurry or change your pants, either one. They may think you're a reception committee."

"Oh, my goodness!" Mr. Rebeck exclaimed. He sprang to his feet. "Thank you, thank you very much. Can't afford to get careless. Thank you for telling me."

"Don't I always?" the raven said wearily. He flew away again with easy, powerful wing strokes. And Mr. Rebeck hurried inside the mausoleum, closed the door, and lay down on the floor, listening to his heart beat in the sudden darkness.

Chapter 2

It was a rather small funeral procession, but it had dignity. A priest walked in front, with two young boys at his right and left. The coffin came next, carried by five pallbearers. Four of them were each carrying a corner of the coffin, and the fifth was looking slightly embarrassed. Behind them, dressed in somber and oddly graceful black, came Sandra Morgan, who had been the wife of Michael Morgan. Bringing up the rear came three variously sad people. One of them had roomed with Michael Morgan in college. Another had taught history with him at Ingersoll University. The third had drunk and played cards with him and rather liked him.

Michael would have liked his own funeral if he could have seen it. It was small and quiet, and really not at all pompous, as Michael had feared it might be. "The dead," he had said once, "need nothing from the living, and the living can give nothing to the dead." At twenty-two, it had sounded precocious; at thirty-four, it sounded mature, and this pleased Michael very much. He had liked being mature and reasonable. He disliked ritual and pomposity, routine and false emotion, rhetoric and sweeping gestures. Crowds made him nervous. Pageantry offended him. Essentially a romantic, he had put away the trappings of romance, although he had loved them deeply and never known.

The procession wound its quiet way through Yorkchester Cemetery, and the priest mused upon the transience of the world, and Sandra Morgan wept for her husband and looked hauntingly lovely, and the friends made the little necessary readjustments in their lives, and the boys' feet hurt. And in the coffin, Michael Morgan beat on the lid and howled.

Michael had died rather suddenly and very definitely, and when consciousness came back to him he knew where he was. The coffin swayed and tilted on four shoulders, and his body banged against the narrow walls. He lay quietly at first, because there was always the possibility that he might be dreaming. But he heard the priest chanting close by and the gravel slipping under the feet of the pallbearers, and a tinkling sound that must have been Sandra weeping, and he knew better.

Either he really was dead, he thought, or he had be

en pronounced so by mistake. That had happened to other people, he knew, and it was entirely possible—not to say fitting—that it had happened to Michael Morgan. Then a great fear of the choking earth seized him, and he pounded on the coffin lid with his fists and screamed. But no sound came from his lips, and the lid was silent under his hammering.

Frantically he called his wife's name and cursed her when she continued her ivory weeping. The priest intoned his liturgy and looked warningly at the boys when they dragged their feet; the pallbearers shifted the coffin on their shoulders; and Michael Morgan wept silently for his silence.

And then suddenly he was calm. Frenzy spent, he lay quietly in his coffin and knew himself dead.

So there you are, Morgan, he said to himself. Thirty-four years of one thing and another, and here is where it ends. Back to the earth—or back to the sea, he added, because he could never remember where it was that all protoplasm eventually wound up. His consciousness did not startle him too much. He had always been willing to concede the faint possibility of an afterlife, and this, he supposed, was the first stage. Lie back, Morgan, he thought, and take it easy. Sing a spiritual or something. He wondered again if there might not have been some mistake, but he didn't really believe it.

A pallbearer slipped and nearly dropped his end of the coffin, but Michael did not feel the jolt. "I don't feel particularly dead," he said to the coffin lid, "but I'm just a layman. My opinion would be valueless in any court in the land. Don't butt in, Morgan. It was a perfectly nice funeral till you started causing trouble." He closed his eyes and lay still, wondering absently about rigor mortis.

The procession stopped suddenly, and the priest's voice became louder and firmer. He was chanting in Latin, and Michael listened appreciatively. He had always detested funerals and avoided them as much as possible. But it's different, he thought, when it's your own funeral. You feel it's one of those occasions that shouldn't be missed.

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand Return

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

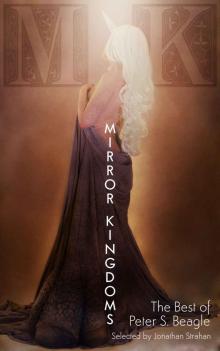

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

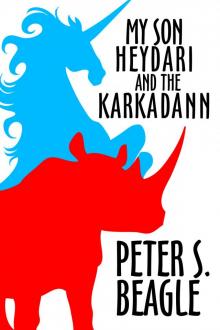

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

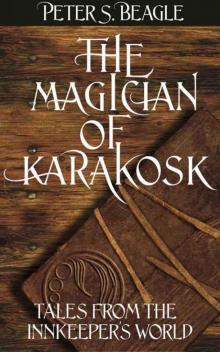

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

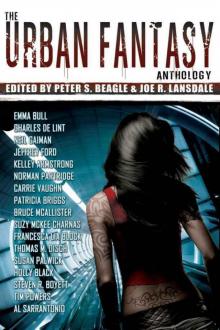

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

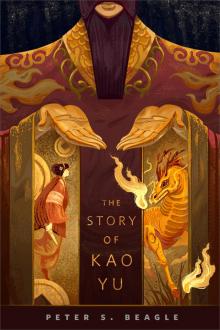

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

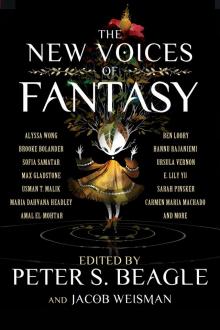

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song