- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

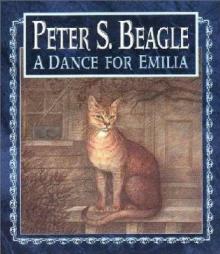

A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia Read online

A Dance for Emilia

Peter S Beagle

Even lifelong friendships can't outlast death...or can they?

Award-winning author Peter S. Beagle presents a deeply personal story of dreams abandoned and recovered, friends loved and lost, and the strength it takes to let go....

A Dance for Emilia

by Peter S. Beagle

For Nancy, Peter and Jessa,

And for Joe

First published as a small stand-alone gift book several years ago, I am pleased to see "A Dance for Emilia" in wider circulation at last. This is the story within these pages that means the most to me. It's fiction, certainly, and very much a fantasy in its nature; but it's also as autobiographical as anything I've ever written, and it was born out of mourning for my closest friend, who died in 1994. His name was Joe Mazo, and we did meet in a high-school drama class, as Jake, the narrator, and his friend Sam do. But Joe was a frustrated actor, not a dancer (just as l'm a writer who, like most writers, would love to be a performer), and who became in fact a well-known dance critic and the author of three highly respected and influential books on modern dance. Jake and Sam's daily lives are as different from Joe's and mine as they were meant to be; but the relationship between them is as close to the way things were as I could write it. As for the original of Emilia, I couldn't really do justice to her, and her love for Joe, but I tried my best.

The Cat. The cat is doing what?

Believe me, it's no good to tell you. You have to see.

Emilia, she's old. Old cats get really weird sometimes.

Not like this. You have to see, that's all.

You're serious. You're going to put Millamant in a box, a case, and bring her all the way to California, just for me to ... When are you coming?

I thought Tuesday. I'm due ten days'sick leave...

No. This isn't how you do it. This isn't how you talk about Sam and Emilia and yourself. And Millamant. You've got hold of the wrong end, same as usual. Start from the beginning. For your own sake, tell it, just write it down the way it was, as far as you'll ever know. Start with the answering machine. That much you're sure about, anyway...

The machine was twinkling at me when I came home from the Pacific Rep's last-but-one performance of The Iceman Cometh. I ignored it. You can live with things like computers, answering gadgets, fax machines, even email, but they have to know their place. I hung up my coat, checked the mail, made myself a drink, took it and the newspaper over to the one comfortable chair I've got, sank down in it, drank my usual toast to our lead—who is undoubtedly off playing Hickey in Alaska today, feeding wrong cues to a cast of polar bears—and finally hit the play button.

"Jacob, it's Marianne. In New York." I only hear from Marianne Hooper at Christmas these days, but we've known each other a long time, in the odd, offhand way of theater people, and there's no mistaking that husky, incredibly world-weary sound—she's been making a fortune doing voice-overs for the last twenty years. There was a pause. Marianne could always get more mileage out of a well-timed pause than Jack Benny. I raised my glass to the answering machine.

"Jacob, I'm so sorry, I hate to be the one to tell you. Sam was found dead in his apartment last night. I'm so sorry."

It didn't mean anything. It bounced off me—it didn't mean anything. Marianne went on. "People at the magazine got worried when he didn't come in to work, didn't answer the phone for two days. They finally broke into the apartment." The famous anonymous voice was trembling now. "Jacob, I'm so terribly ... Jacob, I can't do this anymore, on a machine. Please call me." She left her number and hung up.

I sat there. I put my drink down, but otherwise I didn't move. I sat very still where I was, and I thought, There's been a mistake. It's his turn to call me on Saturday, I called last week. Marianne's made a mistake. I thought, Oh, Christ, the cat, Millamant—who's feeding Millamant? Those two, back and forth, over and over.

I don't know how late it was when I finally got up and phoned Marianne, but I know I woke her. She said, "I called you last. I called his parents before I could make myself call you."

"He was just here," I said. "In July, for God's sake. He was fine." I had to heave the words up one at a time, like prying stones out of a wall. "We went for walks."

"It was his heart." Marianne's voice was so toneless and uninflected that she sounded like someone else. "He was in the bathroom—he must have just come home from Lincoln Center—"

"The Schonberg. He was going to review that concert Moses and Aron—"

"He was still wearing his gangster suit, the one he always wore to openings—"

I was with him when he bought that stupid, enviable suit. I said, "The Italian silk thing. I remember."

Marianne said, "As far as they—the police—as far as anyone can figure, he came home, fed the cat, kicked off his shoes, went into the bathroom and—and died." She was crying now, in a hiccupy, totally unprofessional way. "Jacob, they think it was instant. I mean, they don't think he suffered at all."

I heard myself say, "I never knew he had a heart condition. Secretive little fink, he never told me."

Marianne managed a kind of laugh. "I don't think he ever told anyone. Even his mother and father didn't know."

"The cigarettes," I said. "The goddamn cigarettes. He was here last summer, trying to cut down—he said his doctor had scared the hell out of him. I just thought, lung cancer, he's afraid of getting cancer. I never thought about his heart, I'm such an idiot. Oh, God, I have to call them, Mike and Sarah."

"Not tonight, don't call them tonight." She'd been getting the voice back under control, but now it went again. "They're in shock; I did it to them, don't you. Wait till morning. Call them in the morning."

My mouth and throat were so dry they hurt, but I couldn't pick up my drink again. I said, "What's being done? You have to notify people, the police. I don't even know if he had a will. Where's the—where is he now?"

"The police have the body, and the apartment's closed. Sealed—it's what they do when somebody dies without a witness. I don't know what happens next. Jacob, can you please come?"

"Thursday," I said. "Day after tomorrow. I'll catch the redeye right after the last performance."

"Come to my place. I've moved, there's a guest room." She managed to give me an East Eighties address before the tears came again. "I'm sorry, I'm sorry, I've been fine all day. I guess it's just caught up with me now."

"I'm not quite sure why," I said. I heard Marianne draw in her breath, and I went on, "Marianne, I'm sorry, I know how cold that sounds, but you and Sam haven't been an item for—what?—twelve years? Fifteen? I mean, this is me, Marianne. You can't be the grieving widow, it's just not your role."

I've always said things to Marianne that I'd never say to anyone else—it's the only way to get her full attention. Besides, it made her indignant, which beat the hell out of maudlin. She said, "We always stayed friends, you know that. We'd go out for dinner, he took me to plays—he must have told you. We were always friends, Jacob."

Sam cried over her. It was the only time that I ever saw Sam cry. "Thursday morning, then. It'll be good to see you." Words, thanks, sniffles. We hung up.

I couldn't stay sitting. I got up and walked around the room. "Oh, you little bastard," I said aloud. "Kagan, you miserable, miserable twit, who said you could just leave? We had plans, we were going to be old together, you forgot about that?" I was shouting, bumping into things. "We were going to be these terrible, totally irresponsible old men, so elegant and mannerly nobody would ever believe we just peed in the potted palm. We were going to learn karate, enter the Poker World Series, moon our fiftieth high school reunion, sit in the sun at spring-training baseball camps—we had stuff to do! What the hell we

re you thinking of, walking out in the middle of the movie? You think I'm about to do all that crap alone?"

I don't know how long I kept it up, but I know I was still yelling while I packed. I didn't have another show lined up after Iceman until the Rep's Christmas Carol went into rehearsal in two months, with Bob Cratchit paying my rent one more time. No pets to feed, no babies crying, no excuses to make to anyone ... there's something to be said for being fifty-six, twice divorced and increasingly set in my ways. I'm a good actor, with a fairly wide range for someone who looks quite a bit like Mister Ed, but I've got no more ambition than I have star quality. Which may be a large part of the reason why Sam Kagan and I were so close for so long.

We met in high school, in a drama class. I already knew that I was going to be an actor—though of course it was Olivier back then, not Mister Ed. The teacher was choosing students at random to read various scenes, and we, sitting at neighboring desks, got picked for a dialogue from Major Barbara. I was Adolphus Cusins, Barbara's Salvation Army fiance; Sam played Undershaft, the arms manufacturer. He wasn't familiar with the play, but I was, and with Rex Harrison, who'd played Cusins in the movie, and whose every vocal mannerism I had down cold. Yet when we faced off over Barbara's ultimate allegiance and Sam proclaimed, in an outrageously fragrant British accent, Undershaft's gospel of "money and gunpowder—freedom and power—command of life and command of death," there wasn't an eye in that classroom resting anywhere but on him. I may have known the play better than he, but he knew that it was a play. It was the first real acting lesson I ever had.

I told him so in the hall after class. He looked honestly surprised. "Oh, good night, Undershaft's easy, he's all one thing—in that scene, anyway." The astonishing accent was even riper than before. "Now Cusins is bloody tricky, Cusins is much harder to play." He grinned at me—God, were the cigarettes already starting to stain his teeth then?—and added, "You do a great early Harrison, though. Did you ever see St. Martin's Lane? They're running it at the Thalia all next week."

He was the first person I had ever met in my life who talked like me. What I mean by that is that both of us much preferred theatrical dialogue to ordinary Brooklyn conversation, theatrical structure and action to life as it had been laid out for us. It makes for an awkward childhood—I'm sure that's one reason I got into acting so young—and people like us learn about protective coloration earlier than most. And we tend to recognize each other.

Sam. He was short—notably shorter than I, and I'm not tall—with dark eyes and dark, wavy hair, the transparent skin and soft mouth of a child, and a perpetual look of being just about to laugh. Yet even that early on, he kept his deep places apart: when he did laugh or smile, it was always quick and mischievous and gone. The eyes were warm, but that child's mouth held fast—to what, I don't think I ever knew.

He was a much better student than I—if it hadn't been for his help in half my subjects, I'd still be in high school. Like me, he was completely uninterested in anything beyond literature and drama; quite unlike me, he accepted the existence of geometry, chemistry, and push-ups, where I never believed in their reality for a minute. "Think of it as a role," he used to tell me. "Right now you're playing a student, you're learning the periodic table like dialogue. Some day, good night, you might have to play a math teacher, a coach, a mad scientist. Everything has to come in useful to an actor, sooner or later."

He called me Jake, as only one other person ever has. He was a gracious loser at card and board games, but a terrible winner, who could gloat for two days over a gin rummy triumph. He was the only soul I ever told about my stillborn older brother, whose name was Elias. I knew where he was buried—though I had not been told—and I took Sam there once. He was outraged when he learned that we never spoke of Elias at home, and made me promise that I'd celebrate Elias's birthday every year. Because of Sam, I've been giving my brother a private birthday party for more than forty years. I've only missed twice.

Sam had surprisingly large hands, but his feet were so tiny that I used to tease him, referring to them as "ankles with toes." It was a sure way to rile him, as nothing else would do. Those small feet mattered terribly to Sam.

He was a dance student, most often going directly from last-period math to classes downtown. Wanting to dance wasn't something boys admitted to easily then—certainly not in our Brooklyn high school, where being interested in anything besides football, fighting, and very large breasts could get you called a faggot. I was the one person who knew about those classes; and we were seniors, with a lot of operas, Dodgers games, and old Universal horror movies behind us, before I actually saw him dance.

There was a program at the shabby East Village studio where he was taking classes three times a week by then. Two pianos, folding chairs, and a sequence of presentations by students doing solo bits or pas de deux from the classic ballets. Sam's parents were there, sitting quietly in the very last row. I knew them, of course, as well as any kid who comes over to visit a friend for an afternoon ever knows the grown-ups floating around in the background. Mike was a lawyer, fragile-looking Sarah an elementary school teacher; beyond that, all I could have said about them—or can say now—was that they so plainly thought their only child was the entire purpose of evolution that it touched even my hard adolescent heart. I can still see them on those splintery, rickety chairs: holding hands, except when they tolerantly applauded the fragments of Swan Lake and Giselle, waiting patiently for Sam to come onstage.

He was next to last on the program—the traditional starring slot in vaudeville—performing his own choreography to the music of Borodin's In the Steppes of Central Asia. And what his dance was like I cannot tell you now, and I couldn't have told you then, dumbly enthralled as I was by the sight of my lunchroom friend hurling himself about the stage with an explosive ferocity that I'd never seen or imagined in him. Some dancers cut their shapes in the air; some burn them; but Sam tore and clawed his, and seemed literally to leave the air bleeding behind him. I can't even say whether he was good or not, as the word is used—though he was unquestionably the best: in that school, and more people than his parents were on their feet when he finished. What I did somehow understand, bright and blind as I was, was that he was dancing for his life.

When I went backstage, he was sitting alone on a bench in his sweat-blackened leotard, head bowed into his hands. He didn't look up until I said, "Boy, that was something else. You are something else." The phrase was fairly new then, in our circles at least.

He looked old when he raised his head. I don't mean older; I mean old. The glass-clear skin was gray, pebbled with beard stubble—I hadn't thought he shaved—and the dark eyes appeared too heavy for his face to bear. He said slowly, "Sometimes I'm good, Jake. Sometimes I really think I might make it."

I said something I hadn't at all thought to say. "You have to make it. I don't think there's a damn thing else you're fit for."

Sam laughed. Really laughed, so that some color came back into his face and his eyes became his age again. "Good night, let's just hope I never have to find out." He got dressed and we went out front to meet Mike and Sarah.

He didn't have to find out for some time. We graduated, and I went off to Carnegie Tech in Pittsburgh on a genuine theater scholarship, while Sam stayed home, attending CCNY to please his parents, and literally spending all the rest of his time at Garrett-Klieman, a dance school whose top prospects seemed to be funneled directly into the New York City Ballet. I'd see him on holidays and over the summer, and we'd do everything we'd always done together: going to plays and baseball games, hitting the secondhand bookstores on Fourth Avenue, drinking beer and debating whether the internal rhymes in the songs we were always trying to write were as clever and crackling as Noel Coward's. On Friday nights, we usually played poker with a mixed bag of other would-be actors and dancers. As far as either of us was willing to acknowledge, nothing at all had changed.

But while I talked about plays I'd been in, about Artaud, Brecht, the Living Th

eatre, the Method, improv workshops and sense memories, Sam avoided almost all mention of his own career. If he danced in any of the Garrett-Klieman showcases, he never told me—it was all I could do to persuade him to let me sit in on a couple of his choreography classes. As before, I couldn't look away from him for a moment; but I was already beginning to learn that some dancers, actors, musicians simply have that. It doesn't have a thing to do with talent or craft—it just is, like blue eyes or being able to touch your nose with your tongue. I don't have it.

We were eating lunch at the Automat on Forty-second and Sixth the day he told me abruptly, "They haven't recommended me. Not to City Ballet, not to anybody. It's over."

I gaped at him over my crusty brown cup of baked beans. I said, "What over? This is crazy. You're the best dancer I ever knew."

"You don't know any dancers," Sam said. Which was perfectly true—I still don't know many; I'm not in a lot of musicals—but irritating under the circumstances. Sam went on, "They didn't tell me it was over. I knew. I'm not good enough."

I was properly outraged, not only at Garrett-Klieman, but also at him, for acceding so docilely to their decision. I said, "Well, the hell with them. What the hell do they know?"

Sam shook his head. "Jake, I'm not good enough. It's that simple."

"Nothing's that simple. You've been dancing all your life, you've been the best everywhere you've gone—"

"I was never the best!" The Noel Coward accent had dropped away for the first time in my memory, and Sam's voice was all aching Brooklyn. "You remember that story you told me about Queen Elizabeth—the real one—that thing she said when she was old. 'No, I was never beautiful, but I had the name for it.' It was like that with me. I can be dazzling—I worked on it, I about killed myself learning to be dazzling—but there isn't a move in me that I didn't copy from d'Arnboise or Bruhn or Eddie Villella or someone. And these people aren't fools, Jake. They know the difference between dazzling and dancing. So do I."

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand Return

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

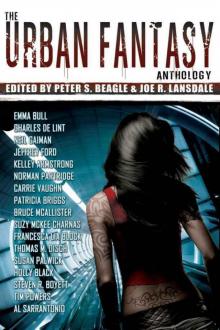

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song