- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

We Never Talk About My Brother Page 13

We Never Talk About My Brother Read online

Page 13

He took Yukiyasa’s elbow respectfully, and they walked slowly away from the river in the fading light. Junko asked, “You will rest here for a few days? It is a long road home. I know.”

The priest nodded agreement. “You will not return with me.” It was not a question, but he added, “Lord Kuroda has not long, and he has missed you.”

“And I him. Tell him I will forget my own name before I forget his kindness.” A sudden whisper of a laugh. “Though I am Toru now, and no one will ever call me Junko again, I think.”

“Junko-san,” Yukiyasa corrected him. “Even now, he always asks after Junko-san.”

Neither spoke again until they had entered the village, and muddy children were clinging to Junko’s legs, dragging him toward a hut further on. Then the priest said quietly, “She really believed she was human. She might never have known.” Junko bowed his head. “Did you believe it yourself, truly? I have wondered.”

The answer was almost drowned out by the children’s yelps of happiness and hunger. “As much as I ever believed I was Junko-san.”

KING PELLES THE SURE

My old friend, the novelist Darryl Brock, has described this as the best anti-war story he has ever read. My vote would probably go to William March’s Company K, which I read at seventeen and have never since gotten out of my head, though I wish I could. Whatever the comparative ranking, I’m proud of this one.

Once there was a king who dreamed of war. His name was Pelles.

He was a gentle and kindly monarch, who ruled over a small but wealthy and completely tranquil kingdom, beloved alike by noble and peasant, despite the fact that he had no queen, and so no heir except a brother to ensure an orderly succession. Even so, he was the envy of mightier kings, whose days were so full of putting down uprisings, fighting off one another’s invasions, and wiping out rebellious villages that they never knew a single moment of comfort or security. King Pelles—and his people, and his land—knew nothing else.

But the king dreamed of war.

“Nobody is ever remembered for living out a dull, placid, uneventful life,” he would say to his Grand Vizier, whom he daily compelled to play at toy soldiers with him on the parlor floor. “Peace is all very well—a fine thing, certainly—but do you ever hear ballads about King Herman the Peaceful? Do you ever listen to bards chanting the deeds of King Leslie the Calm, or read great national epics about King James the Docile, King William the Diplomatic? You do not!”

“There was Ethelred the Unready,” suggested the Grand Vizier, whose back hurt from crouching over the carpet battlefield every afternoon. “Meaning unready for conflict or crusade, unwilling to slaughter needlessly. And King Charles the Good—”

“But it is Charles the Hammer who lives in legend,” King Pelles retorted. “William the Conqueror—Erik Bloodaxe—Alfonso the Avenger—Selim the Valiant—Ivan the Terrible. Our own schoolchildren know those names... and why not,” he added bitterly, “since we don’t have any heroes of our own. How can we, when nobody ever even raids us, or bothers to challenge us over land or resources, or attempts to annex us, to swallow our little realm whole, as has happened to so many such lands in our time? Sometimes I feel as though I should send out a dozen heralds to proclaim our need of an enemy. I do, Vizier.”

“No, sire,” said the Grand Vizier earnestly. “No, truly, you don’t want to do anything like that. I promise you, you don’t.” He straightened up, rubbing his back and smoothing out his robe of office. He said, “Sire, Majesty, if I may humbly suggest it, you would do well—as would every soul dwelling on this soil that we call home—to appreciate what you see as our insignificance. There is an old saying that there is no country as unhappy as one that needs heroes. Trust me when I say in my turn that our land’s happiness is your greatest victory in this life, and that you will never know another to equal it. Nor should you try, for that would show you both greedy and ungrateful, and offend the gods. I urge you to leave well enough alone.”

Having spoken so, the Grand Vizier braced himself for an angry response, or at least a petulant one, being a man in late middle age who had served other kings. He was both astonished and alarmed to realize that King Pelles had hardly heard him, so caught up was he in romantic visions of battle. “It would have to be in self-defense, of course,” the king was saying dreamily. “We have no interest in others’ treasure or territory—we’re not that sort of nation. If someone would only try to invade us by crafty wiles, such as filling a wooden horse with armed soldiers and leaving it invitingly outside the gates of our capital city. Then we could set it afire and roast them all—”

He caught sight of the horrified expression on the Grand Vizier’s face, and added hurriedly, “Not that we ever would, of course, certainly not, I was just speculating.”

“Of course, sire,” murmured the Grand Vizier. But his breath was turning increasingly short and painful as King Pelles went on.

“Or if they should come by sea, slipping into our port on a foggy night, we would be ready with a corps of young men trained to swim out with braces and augurs and sink their ships. And if they struck by air, perhaps dropping silently from the sky in dark balloons, our archers could shoot all them down with fire-arrows. Or if we could induce them to tunnel under the castle walls—oh, that would be good, if they tunneled—then we could....”

The Grand Vizier coughed, as delicately as he could manage it, given the panicky constriction of his throat. He said, “Your Highness, meaning absolutely no disrespect, you have never seen war—”

“Exactly, exactly!” King Pelles broke in. “How can one know the true meaning of peace, who has no experience of its undoubtedly horrid counterpart? Can you answer me that, Vizier?”

“Majesty, I have known that experience,” the Grand Vizier replied quietly. “It was far from here, in a land I traveled to as a boy. I shared it with many brave and dear and young friends, who are all dead now—as I should have been, but for the courtesy of the gods, and the enemy’s poor aim. You have missed nothing, my lord.”

He seemed to have grown older as he spoke, and the king—who may have been foolish, but who was not a fool—saw, and answered him equally gently. “I understand what you are telling me, good Vizier. But this would be only a little war, truly—no more enduring or consuming than one of our delightful carpet clashes. A manageable war—a demonstration, one might say, just to let our rivals see that our people are not to be trifled with. In case they were thinking about trifling. Do you see the difference, Vizier? Between this war and yours?”

With another king, the Grand Vizier would have considered long and carefully before risking the truth. With King Pelles, he had no such fears, but he also knew his man well enough to recognize when hearing the truth would make no smallest difference to what the king decided to do. So he said only, “Well, well, be sure to employ great precision in choosing your foe—”

“Our foe,” King Pelles corrected him. “Our nation’s foe.”

“Our foe,” the Grand Vizier agreed. “We must, whatever else we do, select the weakest enemy available—”

“But that would be dishonorable!” the king protested. “Ignoble! Unsporting!” He was decidedly upset.

The Grand Vizier was firm in this. “We are hardly a nation at all; we are more like a shire or a county with an army. A distinctly small army. A more powerful adversary would destroy us—that is simply a fact, my king. You cannot manage a war without attention to facts.”

He was hoping that his sardonic emphasis on the notion of managing such a capricious thing as war might deter King Pelles from the whole fancy, but it did not. After a silence, the king finally sighed and said, “Well. If that is what a war is, so be it. Consider our choices, Vizier, and make your recommendation.” He added then, rather quickly, “But do arrange for a gracious war, if you possibly can. Something... something a little tidy. With songs in it, you know.”

The Grand Vizier said, “I will do what I can.”

As it turned out, he di

d tragically better than he meant. Perhaps because King Pelles had never wanted to know it, he truly had no notion of how deeply his land was hated for its prosperity on the one hand and coveted on the other. The Grand Vizier had hoped to engineer a very brief war for the king, quickly over, with minimum damage, disruption or inconvenience to everyone involved, and easily succeeded in tempting their little country’s nearest neighbor to invade (in the traditional style, as it happens, by marching across borders). But his plan went completely out of control in a matter of hours. Wise enough to lure a weaker country into a foolish attack, he was as innocent, in his own way, as his king, never having considered that other lands might be utterly delighted to join with the lone aggressor he had bargained for. An alliance of territories which normally despised each other formed swiftly, and King Pelles’s land came under siege from all sides.

Actually, it was no war at all, but a massacre, a butchery. There was a good deal of death, which was something else the king had never seen. He was still shaking and crying from the horror of it, and the pity, and his terrible shame, when the Grand Vizier disguised them both as peasant women and set them scurrying out the back way as the flaming castle came down, seeming to melt and dissolve like so much pink candy floss. King Pelles looked back and wept anew for his home, and for his country; and the Grand Vizier remembered the words of Boabdil’s mother when the Moorish king looked back in tears from the mountain pass at lost Spain behind him. “Weep not like a woman for the kingdom you could not defend like a man.” But then he thought that defending things like men was what had gotten them into this catastrophe in the first place, and decided to say nothing.

The king and his Grand Vizier scrambled day on wretched day across the trampled, smoking land, handicapped somewhat by their long skirts and heavy muddy boots, but running like a pair of aging thieves all the same. No one stopped them, or even looked at them closely, although there were mighty rewards posted everywhere for their heads, and they really looked very little like peasant women, even on their best days. But the country was in such havoc, with so many others—displaced, homeless, penniless, mad with terror and loss—fleeing in every direction, that no one had the time or the inclination to concern themselves with the identities of their poor companions on the road. The soldiers of the alliance were too busy looting and burning, and those whose homes were being looted and burned were too busy not being in them. King Pelles and the Grand Vizier were never once recognized.

One evening, dazed as a child abruptly awakened from a happy dream, the king finally asked where they were bound.

“I have relatives in the south country beyond those hills you see,” the Grand Vizier told him. “A cousin and her husband—they have a farm. It has been a long time since I last saw them, and I cannot entirely remember where they live. But they will take us in, I am sure of it.”

King Pelles sighed like the great Moor. “Better your family than mine. My cousins—my own brother—would demand a bribe, and then turn us over to the conquerors anyway. They are bad people, the lot of them.” He huddled deeper into his ragged blanket, shrugging himself closer to their tiny fire. “But I am the worst by far,” he added, “the worst, there is no comparison. I deserve whatever becomes of me.”

“You did not know, sire,” the Grand Vizier offered in attempted solace. “That is the worst that can be said of you, that you did not know.”

“But you did, you did, and you tried to warn me, and I refused to listen to you. And you obeyed my orders, and now you share my fate, and my people’s innocent lives lie in ruins, and it is my doing, and there is no atoning for it.” The king rocked back and forth, then stretched on the ground in his blanket, as though he were trying to bury himself where he lay, whimpering again and again, “No atoning, no atoning.” He hurt himself doing this, for the ground was shingly and rock-strewn. The Grand Vizier knew he would see the bruises in the morning.

“You were a good king,” the Vizier said. “You meant well.”

“No!” The word came out as a scream of agony. “I never meant well! I meant glory for myself—nothing less or more than that. And I knew it, I knew it, I knew it at the time, and still I had to go ahead, had to play out my toy battle with soft, breakable human bodies, breakable human souls. No atoning....”

There was nothing for the Grand Vizier then, but to say, as to a child, “Go to sleep, Your Majesty. What’s done is done, and one of us is as guilty as the other. And even so, we must sleep.”

But he himself slept poorly—perhaps even worse than King Pelles—in the barns and the empty cattle byres and the caves; and the king’s piteous murmurings as he dreamed were hardly of any help. There was always the smell of smoke, from one direction or another; at times there would come noises in the night, which might as easily have been restless cows as pursuing spies or soldiers, but there was never any way for the Vizier to make certain of either. All he allowed himself to think about was the need to guide the king safely to shelter from one night to the next—further than that, his imagining dared not go, if he meant to sleep at all. And even if we find my cousin—what was her husband’s name again?—even if we do find their farm, what then?

By great good fortune, they did find the Grand Vizier’s cousin, whose name was Nerissa—her husband’s name was Antonio—and were welcomed as though they had last visited only days ago, or a week at most. The little farm was a crowded place, since Nerissa and Antonio, with no children of their own, had gladly taken in their widowed friend Clara and her four, who ranged in age from six to seventeen years. Nevertheless, they received King Pelles and the Grand Vizier unhesitatingly: as Antonio said, “No farm was ever the worse for more hands in the fields, nor more faces around the dinner table. And whoever noticed the smudged and sunburned face of a farmworker who wasn’t one himself? Have no fear—you are safe with us. In these times, there is no safety but family.”

So it was that he who had been the king of all the land and he who had been its most powerful dignitary became nothing more than hands in the fields, and were grateful. Neither was young, but they worked hard and long all the same, and proudly kept even with Antonio and the others when it came time to bring the harvest home. And every evening, King Pelles told stories about wise animals and clever magicians to Clara’s children, and later the Grand Vizier conducted an informal history lesson for the older ones, in which their mother often joined. Still an attractive woman, she had clear brown skin and dark, amused eyes which were increasingly attentive, as time passed, to whatever the Vizier said or did. Antonio and Nerissa saw this, and were glad of it, as was the king. “Your cousin has wasted his life on my foolishness,” he said to Nerissa. “I am so happy that she will give it back to him.”

When the Grand Vizier could do it without feeling intrusive, he listened—with the back of his head, perhaps, or the back of his mind—to the king’s fairytales. They were not like any he had ever heard, and they fascinated and alarmed him at the same time. Few had what he would have considered happy endings, especially as a child—the gallant prince frequently failed to arrive in time to rescue the princess from the dragon, more often than not the poison was not counteracted, the talking cat could not always preserve his master from his own stupidity. Endings changed, as well, with each telling, and characters wandered from one story into a different one, often changing their natures as they did so. On occasion grief flowed into overwhelming joy, though that outcome was never something you might want to bet on. The Grand Vizier constantly expected the children to become frightened or upset, but they listened in obvious absorption, the younger ones crowding each other on the king’s lap, and all four nodding silently from time to time, as children do to express trust in the tale.

Maybe it is the way he tells them, the Grand Vizier thought more than once, for King Pelles always had a special voice at those times, different than the way he spoke in the fields or at evening table. It was a low voice, with a calmness in it that—as the Vizier knew—had grown directly from suffering

and remorse, and seemed to draw the children’s confidence whether or not the words were understood.

Yet content as King Pelles was in his new life, fond of Clara’s children as he was, warmed far deeper than his bones by being a true part of a family for the first time... even so, he still wept in his sleep, whispering brokenly, “No atoning....” The Grand Vizier heard him every night.

Winter was always hard in that kingdom, even in the south country, but the Grand Vizier was profoundly glad of it. The snow and mud closed the roads, for one thing: there would be no further pursuit of the king for a time, and who knew what might happen, or have happened, by spring?

What news reached the farm suggested that a group of the king’s former advisors had banded together to install a ruler of their choosing, and thus restore at least their notion of order to the kingdom, but the Vizier could not discover his name, nor learn any further details of the story. But he allowed himself to be somewhat hopeful, to imagine that perhaps—just perhaps—the hunt might have dwindled away, and that the king’s existence might have become completely unimportant to the new regime. For the first time in his long career of service, the Grand Vizier dreamed a small dream for himself.

But with the thawing of the roads, with the tinkling dissolution of the icicles that had fringed the farmhouse’s gables for many months, with the first tentative sounds of the frogs who had slept in the deep beds of the frozen streams all winter... the soldiers came marching. With the first storks, they came.

Martine, Clara’s younger daughter, was playing by the awakening pond one afternoon, and heard their boots and the rattle of their mail before they had rounded the bend in the road. She, like all the others, had been told over and over that if she ever saw even one soldier she must run straight to the house and warn her mother’s special friend, and the other one as well, the storyteller. She never waited to see these, but was up and away at the first sound, and through the front door in a muddy flash, crying, “They’re here! They’re here!”

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand Return

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

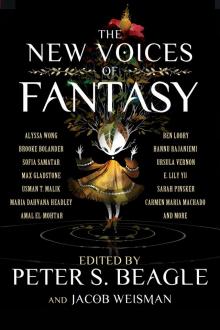

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song