- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

We Never Talk About My Brother Page 17

We Never Talk About My Brother Read online

Page 17

Another vast, sweaty shrug, another mouthful of lox. “I don’t do exorcisms. They’re messy, and they only work on demons, anyway. This one’s just an aggrieved householder with an obsession. Misguided, but one could sympathize. And after all, he can’t really hurt you. In any significant way.”

Farrell growled at him. Andy Mac considered, pulling at his lower lip, which made Ben feel slightly seasick. “Well, there’s one thing....” Another dramatic pause, lasting so long that Ben put his hand on Farrell’s shoulder, in case of accidents. He was confident that Farrell hadn’t murdered the Spook, but he wasn’t a bit sure about his intentions toward Andy Mac. But Farrell only said two words, both of them through his teeth. “What? Talk.”

“What happened to those teacakes?” The phone rang as Ben was bringing them over, but no one even looked toward it. Andy Mac grabbed a fistful of the cookies and said, “Let’s see what he wants. He knows he can’t have the revenge he craves, but I’ll bet he’s got something in mind. Ghosts have agendas, like everybody else, and agendas go last.”

The Spook dived at Farrell again, who shot back into the closet with a wail of despair, “Damn it, this shit has got to stop!” The ghost swerved away from the door once again and hung in the air, chittering like a pissed-off squirrel. Andy Mac heaved himself up and out of the armchair, cocking his head sideways, listening as intently as though the Spook were reciting Tonight’s Seafood Specials. Then he started to laugh.

Andy Mac’s laugh was rare, but legendary among his acquaintances. Julie had once compared it to a volcanic mud slide she had seen in the Philippines. He shook, and he coughed, and he rumbled and gurgled, and he twitched all over, and the corners of his mouth got wet. Even the Spook stopped carrying on to stare at him—eyeless and faceless as it was—and Andy Mac just kept laughing.

When he did stop, on an inhale that sounded like a moose pulling its feet out of a swamp, he yelled, “Farrell! Get out here!”

From the closet, Farrell answered, “Not a chance. I’m running cable in here and sending out for Chinese.”

“Get out here,” Andy Mac repeated. “Walter won’t attack you.” To the Spook, he added, “You don’t mind me calling you Walter?”

The answer appeared to be in the affirmative. Farrell returned, slowly and cautiously, making sure to keep an escape route clear. The Spook’s shrill snarl rose higher, but it stayed where it was. Andy Mac said, “Farrell, this is the late Walter Smith—at least, he thinks that might have been his name. Walter, meet Joe Farrell.” He might have been introducing them at a faculty cocktail party.

“Tell him I didn’t kill him,” Farrell demanded. “I mean, I wouldn’t mind killing him now, but I didn’t do it then. Tell him!”

“Won’t do any good. Doesn’t even register.” Andy Mac crunched down the last of the Russian teacakes and wiped his sugary hands on his pants. “Anyway. Walter is challenging you to a duel.”

It was as though Farrell had been expecting something like this: Ben’s memory afterward was that he himself was the one who protested “This is crazy!” while Farrell mostly looked back and forth between Andy Mac and Walter the Spook, while the phone rang unanswered again, and Ben went on making loud noises. Finally he said the obvious. “But what’s the point of it? Even if he could hold a weapon, he can’t hurt me—so what’s in it for him? What kind of a revenge is that?”

“There are other weapons than swords and pistols,” Andy Mac replied, “and other stakes than life and death. You can’t hurt him either, obviously, and you get to choose the armaments, because you’re the challenged party. But he gets to set the terms.” He smiled like an oil spill. “If you win, Walter will never bother you again. Period. No strings, no small print. He’ll be here, because he lives here, but you’ll never see him. Fair enough?”

Farrell nodded. “And if he wins?”

“Ah,” Andy Mac said. “Well. It appears that our Walter has conceived something of a tendresse for the absent Ms. Tanikawa. He gets a bit incoherent here, but he certainly thinks that she’s much too good for the man who murdered him.”

“Damn it, I didn’t—” Farrell began, but then he stopped himself and said only, “Julie’s not part of the deal. That is not negotiable.”

Andy Mac shrugged. “If you lose, you leave. Nothing to do with your lady. You make what excuse you like—you even tell her the truth, if that’s your idea of a good time—and you’re permanently off the premises by dinnertime tomorrow, before Ms. Tanikawa returns on the following day. That simple.”

“Not really,” Farrell said. “If I tell Julie why I’m having to move—and yes, I will—she’ll walk right out with me, like a shot, I promise you. Julie rather hates being manipulated.” He grinned tauntingly up at the Spook fluttering overhead. “Where’s your tendresse then, Walter, old buddy?”

The oil spill smile spread, and Andy Mac answered him. “Walter has listened often to Ms. Tanikawa expressing her own tendresse for this loft. He’s willing to chance it.”

Ben glanced anxiously at Farrell, remembering their morning’s conversation. Julie wouldn’t ever leave this loft, not even for Farrell, nor would he have expected her to. He’d been bluffing, and it hadn’t worked. But Ben saw him recouping, gathering his psychic feet under him, bracing himself for whatever came next. He took a long, slow breath.

“All right,” Farrell said. “All right, then. The duel will take place precisely at dawn tomorrow. I’ll choose the weapons then. Right now, it’s late, and I’ll require a peaceful night and morning to make my decision. I trust that won’t be a problem?”

“No problem at all,” Andy Mac answered for the Spook. “Just so the combat doesn’t turn on manual dexterity.”

“Me? Hardly.” Farrell turned to Ben. “You’ll be my second?”

“Like I’ve got a choice. What’s a second expected to do?”

Farrell was brisk. “Oh, you check out the weapons, and you carry my body home if I lose, and you tell Julie I died bravely. The usual. You’ve seen the movie.”

Andy Mac said that he’d second the Spook, out of fairness and necessity. “Like a public defender, backbone of our system.” The phone rang once more, and this time Farrell picked it up. It was Julie, as the other two calls had been, letting Farrell know the time and number of her flight from Seattle. Andy Mac left, and Ben went to haul out the air mattress and sleeping bag he always used staying over with Farrell and Julie. When he came back, the phone call was finished, and Farrell was lying on his bed with his hands behind his head, staring at the ceiling. And where Walter the Spook spent the night, neither of them had the least idea.

Farrell didn’t move or speak while Ben undressed and crawled into the sleeping bag; but then he murmured thoughtfully, more to himself, “I wonder who did kill old Walter Smith, all that time ago. Aggravating, never to know.”

“Well, if he was anything like the way he is now, they could have sold tickets. Held a raffle.” Farrell chuckled softly. Ben said, “About why Andy Mac hates you.”

“I told you... long story.”

“You also told me he went for the gig on the chance of getting even. What did you do to him, for God’s sake?” Farrell did not answer. Ben said, “I really hate to call in old markers, but you remember that paper on Moby-Dick? You remember your grade? I do.”

“You’re a very hard man,” Farrell said after a further silence. “You were a very hard five-year-old.” He sighed. “It’s not as long a story as all that, I just don’t come out of it looking very good. Andy Mac’s a snob and a showoff, but he’s not a monster, not even a bad guy, really. He’s got a whole lot to show off, lord knows, but it’s not enough, it’s never enough. And he has to be right, has to—it’s that important to him. Anyway, some time back, years, there was this party, and he was working on impressing Julie—”

“Julie? I never thought Andy Mac liked girls that way.”

“I don’t think he really likes anybody that way. But he dearly likes making an impression, subject doesn’t

matter. So he was lecturing her about James Joyce and Finnegans Wake—and maybe I got jealous, maybe the devil made me do it, but I butted in and started talking about this Romanian linguistics professor, whom I made up on the spot, and how he had this big theory that Joyce was actually... what did I say, a Mason? No, I said the Romanian guy proved beyond doubt that Joyce was a Rosicrucian, and I quoted whole passages from his well-known book on Joyce—”

“Which, of course, Andy Mac knew by heart. Oh, lord, I see where this is going—”

“Right, he was great, really. Improvised better than I did—explained to Julie how Finnegan’s Wake was absolutely transparent, once you understood the code. And she looked at him, and then she looked at me, and people were listening... and I sort of wandered off—”

“And by and by, the word got back to him.... Oh, you’re bad, Farrell. That was a terrible thing to do. I’m ashamed of you.”

“What can I tell you? I was younger then.”

“And you think he’s still carrying a grudge about that?”

“I know he is.”

Ben slept fitfully, and Farrell not at all, so both were up well before dawn. The Spook was still invisible, and Andy Mac wasn’t due till showtime, so Ben made Eggs Benjamin, as requested—notorious on two continents or not—plus a pot of equally notorious coffee, and went for a walk in the still-misty streets to keep himself from staring and pacing and offering helpful suggestions. They had seen each other through other dawns, and other duels.

He had left his cell phone on, which was a good thing, because Farrell called halfway through his fourth time around the block. “Come on back—I need you to look up some stuff for me! Hurry!”

Ben ran up the two flights, sounding exactly like Andy Mac when he lurched through the door, and sat down at Julie’s computer to look up stuff. He printed it out as he came across it, and Farrell sat there reading and reading; and for a few hours it was like the old times of studying together, trying to write dates and formulas all over shirt cuffs, and even fingernails. Farrell had always had the better memory, and if Ben had envied it then, he was glad of it now. They spoke very little.

They stayed at it until they heard Andy Mac at the door, which Ben opened before he could knock. It seemed to annoy him. He was dressed for opening night at the opera: evening clothes, white tie, gorgeous red-and-gold cravat, lacking only the silk hat. He looked surprised to see Ben in everyday street clothes, and more than a bit contemptuous as well. He said, “I understood that proper seconds wore proper clothing to a duel of honor.”

“Well, I’m an improper second.”

Farrell looked up for a moment and waved languidly before he went back to reading. Ben said, “Hey, this isn’t the Bois de Boulogne. We’ll be ready come sunrise.”

Andy Mac had to leave it at that, and leave it with no snacks this time, no Johnnie Walker Black to occupy him until the hour of the duel. Ben could watch him getting more and more annoyed, and couldn’t help sympathizing: here he’d gotten totally, uncharacteristically, involved in an affair that not only wouldn’t feed him, but was most likely going to turn out too weird even to dine out on. He said finally, “You know, it wouldn’t hurt you to see the man’s point of view.”

Farrell didn’t bother to look up this time. “He has no point of view. What he has is a thing about my girlfriend, and he’ll make our lives hell if I don’t get out and give her up. I’m sorry, but that’s not a point of view. That’s a hissy fit.”

“But he was murdered!” Andy Mac bellowed.

Farrell shrugged, long and slow, and very deliberate. “That’s not a point of view either. I didn’t do it, and I’m tired of him saying I did. In this century, in this country, that’s considered slander. I may very well sue.”

“After all, you’ve only got his word for it,” Ben added. “And we already know about him.” To his own surprise, he was actually starting to enjoy this—especially watching the dampness spreading under Andy Mac’s tuxedoed armpits. “Old Walter might be amusing himself, attacking Farrell and spinning all this shit out for you, just because he’s bored out of his mind. It’s not exactly much of a life he’s got, is it?”

He swept his arm up toward the ceiling in a dramatic gesture, and that was when he saw Walter the Spook perched up in the rafters. To be accurate, not having anything to perch with, he was hovering, as hummingbirds do, and definitely vibrating like a hummingbird, ready for the duel, ready for his close-up. Probably the most exciting thing that’s happened to him in the last hundred years. Ben couldn’t help wondering what weapon he might have chosen if Farrell had been the challenger. Maybe he did have hands—though there had been no sign of any—maybe he could be hiding a couple of Derringers up in those empty, floppy scarlet sleeves. Is a ghost simply what you always were, inside? What does it tell us that he’s this?

Andy Mac looked at his watch and said, “Sunrise in five minutes. I think we might get started.”

“Dawn,” Farrell said firmly. So they waited out the last five minutes, with Walter the Spook plainly struggling with a profound and passionate need to start diving at Farrell again, and Farrell peacefully ignoring everybody, looking through papers and making a few notes, as though he were prepping for a final. Ben stood by, waiting for instructions, as previously agreed. Farrell unplugged the phone.

“Okay,” he said. “Now.”

He said nothing more, but only sat there, smiling a little bit at nothing in particular. What seemed like another five minutes went by before Andy Mac finally said, “Now what?”

“Now I name the weapons,” Farrell said. “And the terms.” The smile broadened, but this time it was aimed directly at the Spook above their heads. Farrell said, “Bad poetry at twenty paces. To the death.”

In the silence that followed, he added, “Really bad poetry,” just before Andy Mac went up in smoke.

“What the hell are you talking about? You can’t fight a duel with poetry!”

“You can with these,” Farrell replied happily. “Trust me, it’ll be like dueling with cobras, crocodiles.” He was as purry and sleepy-eyed as a kitten serenely attached to a nipple. “Wait till you hear a couple of sparkling stanzas from Julia A. Moore... Margaret Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle... J. B. Smiley. Oh, your boy is toast already, Andy, burned toast. Honestly, I’d tell him to hang it up now, in the first round.”

Whether or not Walter the Spook was capable, at this point in his career, of fully comprehending human speech, Ben had no idea, but he never doubted that the ghost got the gist. He was squalling like a buggered banshee before Farrell was half through; but instead of going for him, he flew down straight to Andy Mac, looking a bit like an old-fashioned ear trumpet as he yammered to him. Andy Mac was all attention, listening so intently that the listening was visible: Ben felt he could actually see the translation going on in his head, the frontal lobes and cerebellum wringing meaning out of angry gibberish. He couldn’t help wondering whether Walter the Spook had originally spoken Estonian.

“Well,” Andy Mac finally announced. “Speaking as Mr. Smith’s second, I must immediately register a formal protest. It’s shameful and immoral to force a person to fight with a weapon with which he is completely unacquainted, and with which you—I’m quite certain—are an expert.” Farrell inclined his head modestly. “And for my own curiosity, how can such a duel possibly be considered a combat to the death? It may be absurd, and even humiliating, but there’s nothing lethal about even the worst poetry.”

Farrell didn’t answer immediately. When he did, his voice was quiet and reflective, and not at all mocking. He said, “You know, Andy, in a way I owe your little red buddy something very important. Something I might never have realized without his intervention. Tell him I’m really grateful.”

Andy Mac very clearly did not want to ask the question, but there was just as clearly no way not to. “Grateful for what?”

“For teaching me that I want to stay where I am,” Farrell said. “It never used to matter to me.

One place, one job, one pleasant, convenient other... it’s always been like any other place, any other person, you know? But not now, some way. Not now.” He stood up, again addressing himself to Walter the Spook. “Even if I moved out tomorrow, you still wouldn’t have a chance with Julie. I’d find a place of my own—there’s a neat little two-bedroom right by the restaurant—and she’d likely be over there when she wasn’t working here. That’s the way we’ve always lived, all these years—except sometimes over there was in another time zone, or another country. Or maybe here was, depending. A lot of years like that.”

Andy Mac started to say something, but Farrell cut him off. “But not now. It’s a funny thing,”—he hesitated for a long moment—“but now I think that leaving this particular dump actually would mean some kind of death for me. So there’s a certain lethal incentive, you could say, right?”

The Spook chattered furiously, but Andy Mac paid no heed. Farrell continued, “And as for what’s at risk for the good Walter... well, I’m not just talking about sentimental Hallmark cards. I’m talking poetry so bad that a wise man would listen to it through smoked glass. Poetry that sets the blood cringing backwards in your veins—poetry from which one’s very kidneys shrink, poetry that curdles the lymph glands and makes the teeth whine like dogs.” His voice had acquired the half-taunting urgency of a carnival pitchman. “Poetry so horrid, the brain will simply refuse to recognize it as English, let alone verse. Be warned—oh, be warned—it’s deadly stuff, toxic as the East River.” He smacked his hands together, grinning a werewolf grin. “Let’s go!”

He began stepping off twenty paces, while Walter the Spook dithered shrilly, and Andy Mac said, “You know I’m going to have to speak for him, translate for him. That’s only fair.”

“You’re his second,” Farrell said calmly, still counting, with his back to the others. “I want him to have every proper advantage.” He turned at the far wall, where Julie habitually hung paintings and drawings she had doubts about and wanted to live with for a while—she called it the “Parole Wall”—and said, “I’ll even give him the first shot. Fair?”

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand Return

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

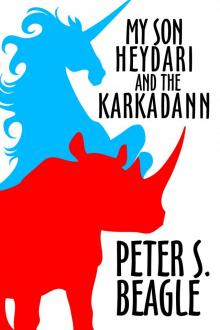

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

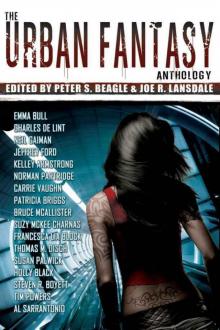

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

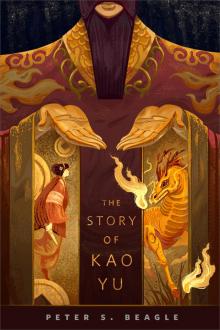

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

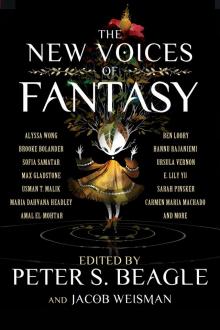

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

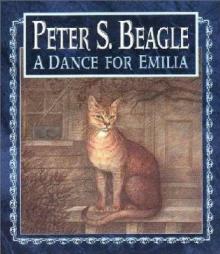

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song