- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

We Never Talk About My Brother Page 19

We Never Talk About My Brother Read online

Page 19

Farrell nodded. “Right away. She always finds stuff like this out, anyway—I might as well get points for candor. I think she might even be flattered, a bit. Not too flattered, but still. And she’ll feel sorry for him, sure as hell, I know the woman.” He sighed. “It’s as I said, Ben—the poor guy really did teach me something I didn’t want to know, and I do owe him, some way. Believe me, I’ve gotten used to way weirder stuff in my time, and so has Julie. Just so he’s quiet. Quiet, I can live with. And invisible. We’ll deal.”

Ben said, “I stay with you guys, I always hate to go home.”

“Oh, you’re much better off in Los Angeles. There’ve been times when it was all I could do not to go home with you. Julie too, probably. Things just keep happening here.” Another sigh; and then that bent, warped, crookedy smile that he had in the first grade. “Besides, you must never forget the immortal words of our Julia—the Goddess herself.”

“Which are?”

“‘Literary is a work very difficult to do.’”

“Amen and amen,” Ben said. He reached for the last bottle of Aventinus, but Farrell slapped his hand.

THE STICKBALL WITCH

Everything in this story is as real and true of my 1940s/1950s Bronx childhood as I can remember it. One of my two closest childhood friends has already assured his grown kids that it happened exactly as recounted; and the other one would cheerfully swear the same, if properly remunerated. This was written to be read aloud as the first of five season-themed podcasts for a delightful online magazine called The Green Man Review. It was my nod to spring.

I was a boy, and it was spring in the Bronx. School would be out in less than two months. My friend Phil’s folks had just gotten a television set, and he and I could watch Ralph Bellamy in Man Against Crime on Friday nights. There was a new war on in Korea, and red-haired Sandy Greenbaum was being even more insufferable than usual because her big brother Sam was some kind of aide to General Mark Clark, whose name she always pronounced in full, like an incantation. Or perhaps a prayer, I wonder now: who knows how frightened for Sam her family actually was? Maybe saying the general’s whole name was a way of not stepping on a crack, not breaking the charm that would bring her brother home whole himself? What did I know? I was eleven years old, and she was obnoxious and had freckles.

I was eleven, and it was spring. The dogwood was blossoming in the cemetery down the block; the park two blocks away in the other direction was bright with budding goldenrod, and would be brilliant with forsythia and ragweed in another week or so. My allergy shots had already begun; but so, one after another, also like wildflowers in their season, had rollerskates and bicycles, jacks and Double Dutch and hopscotch (which we called “potsy”) for the girls, catch and one-o’cat and schoolyard fights for the pure hell of fighting for the boys. And stickball. Between one day and the next, stickball again.

Stickball is—was, I guess; who plays it now?—street baseball, played with broomsticks and a specific kind of ball. It was manufactured by the Spalding Company—though I never heard it called anything but a Spaldeen—and was made of a particular kind of pink rubber, which emitted a flaky whitish powder when fresh, and smelled indescribably of... of spring, finally, and of laundry drying on apartment-building roofs and on lines strung between apartment windows, and sunlight lasting a little longer every day. In the Bronx in 1950, spring smelled like Spaldeens.

There were never enough players to make up two full teams; it was quite common for boys to play for both sides, as necessary. (Although choosing up sides, arguing over the fairness of which team got stuck with which fat or slow or stone-fingered kid, could easily take longer than the game itself.) As for the playing field, the ground rules literally varied with the parking along Tryon Avenue that afternoon. First and third bases were almost always cars, though we made do with bicycles or wagons when we had to; second and home were usually one manhole cover apart, though this might be affected by the spatial relationship of first and third. Since we were always short on fielders (if anyone actually had a glove, it usually wound up being a base), a hit that traveled as far as two manhole covers’ distance was an automatic double; so, also, was a ball hit into traffic, wedged under a car or carried away forever by Richie Williams’ damn dog. A three-manhole shot was a triple. Home runs... well, fat Stewie Hauser hit one once, far down the block toward the cemetery, and mean Joey Gonsalves hit one that he said was a homer, go argue with Joey Gonsalves. He had brothers.

Of course, we could have walked two blocks to the park and played on a real baseball diamond, but that was just the point of stickball. It had to be played with sticks, not real bats, balls and gloves; it had to be improvised, from equipment to the contours of the baselines to the constantly-evolving rules, which were quite likely to be significantly different over on Decatur Avenue, or DeKalb. You played baseball or softball in the park—stickball was for the street, only and always. Not all of life was that simple, even in 1950, even at the age of eleven, but stickball... oh, stickball, yes.

I wasn’t good at stickball; let’s have that clear. I wasn’t one of those chosen last, or forced on one team or the other like a handicap, but I was a lot closer to that social class than to the stars like Stewie Hauser, Miltie Mellinger or J.T. Jones. The only athletic gift I had was that I could run, which wasn’t much use in our game, since we didn’t have stolen bases, the way they played down on Rochambeau Avenue. If I actually connected, I’d make it home well before anybody ran the ball down, but it didn’t happen often. To this day, I remember every time that it did.

Today Tryon’s lined with condos on both sides, but back then there were still a lot of trees, and a lot of one-family houses: thirty, forty years old, older, most still occupied by the original owners, who had built and settled in when the Bronx was still largely farming country, and my mother would often meet a cow or a goat on her way to school. Fragments of those farms survived in my own school years: they were usually inhabited by half-mad hermits who threw stones at kids trying to cut through their overgrown fields and blighted orchards. All gone now, of course, all leveled and paved over by the end of that decade. I’m not nostalgic. I just remember.

Tryon Avenue had a witch. Many streets did; it was almost a necessity to local tradition, back when a single block, a single apartment building, was an entire country for a child, complete with history, royalty, a peasant class, endless threats from outsiders, and a rich and varied folklore. The designated witch was always some old lady living alone, quite often foreign-born and oddly dressed (by our highly Puritanical standards for adults); and known to us, beyond any reasonable doubt, as implacably menacing, whether or not she’d done anything at all to merit the verdict. Whatever else they had in common, the universal factor—going all the way back to the Brothers Grimm, and surely beyond—was that any ball hit into their front yards, or their ragged little gardens, stayed there forever. We were often surprisingly daring—foolhardy, even, looking back—but we weren’t crazy.

Mrs. Poliakov was our witch. She lived about halfway down the block, in a small gray house, which I keep seeing as stone, though I’m sure it wasn’t, no more than it could have been gingerbread. Mrs. Poliakov almost never left the gray house; such deliveries as she needed came to her, as was more common in those days. Since we hardly kept exact track of just who went into the house and who came out, we were happy to spread—and, by and by, absolutely believe—a rumor that Mrs. Poliakov sometimes ate deliverymen, or turned them into... things. Which would certainly account for the absence of a Mr. Poliakov, after all. We thought hard about stuff like that. We had discussions. We ruminated.

She was a tiny woman, really, gray and nondescript as her house, but we equipped her with fangs (if you looked closely, which nobody was about to do), and with what the Italian kids called the mal’occhio, and the Puerto Ricans the mal ojo—the evil eye. My memory has her backing carefully down her front steps when she did come out, usually wrapped in an old tweed overcoat, no matter the weather.

She always wore a man’s battered felt hat, and she limped a bit on her right leg.

Spaldeens hit into Mrs. Poliakov’s yard, as I’ve said, were lost balls, even though we could usually see them where they lay against her fence, often actually within reach through the wobbly, peeling slats. She never threw them back, of course, but she never got rid of them either, so there they lay like spoils of some mysterious war nobody but the participants remembered. We visualized her gloating over them, using them to cast spells, as we knew beyond question she did. For spite we threw other things into her yard at night—rotting garbage, dead animals, paper bags filled with patiently-collected dog and cat shit—and then ran like hell. I felt bad sometimes, thinking about it... but that’d teach her to be sitting up midnights, casting spells.

What changed everything—especially for me—was the day Chuck Golden dared me to go get the ball that I’d just fouled off into Mrs. Poliakov’s front yard. (Anything in the street, including parked cars and Schwartz’s fruit truck, was fair territory; the curbs were our foul lines.) Chuck Golden was a sawed-off loudmouth, but that Spaldeen happened to be our last one, and it was just wrong to quit playing on a Saturday, with the sun still high. Junius Dinkins, who usually had more sense, said, “You hit it, you oughta get it,” and Stewie Hauser—always the second guy to do or say anything, said he double-dared me. So there it was. You couldn’t walk away from a double-dare, even from a dumbshit like Stewie. I mean, you could, but the rest of your life wouldn’t ever be worth living after that. I knew that then. Not believed. Knew.

But I also knew absolutely that if I entered that yard, I’d never come back. Not as myself, anyway – maybe as some kind of monster, which was almost tempting when I thought of Joey Gonsalves and all his brothers. What if Mrs. Poliakov grabbed me in her claws and dragged me into her house—that house we’d spent hours peopling with every horror we’d ever seen in a movie or a comic book? Oh, sure, my mom and dad would call the cops. But what good would the police be if I’d already been eaten, or fed into a meat grinder, or turned into furniture? I wasn’t aware of it until later, but it was in that moment that I woke up to the realization that you couldn’t depend on your parents in a real crisis, any more than you could on the police. I never managed to unlearn that discovery, though I did try.

But when you’re eleven years old, there’s no such thing as a choice between being a witch’s afternoon snack or being a fink and a chickenshit. I made the best scene I could (having already seen A Tale of Two Cities) out of accepting my doom; and, rot them, the team played right back to me. They didn’t exactly ask for any last messages to my nearest and dearest, but J.T. Jones shook my hand hard, and Miltie gave me back the immie he’d won off me two weeks before. And I handed my broomstick to Richie Williams—as formally as if it were a sword or a custom-made pool cue—and I made my legs walk me straight across the street and into Mrs. Poliakov’s front yard.

I picked up the ball I’d hit, suddenly entertaining a mad notion of scooping up as many others as I could carry and racing back in triumph from behind enemy lines with an armload of trophies to flaunt, both at Chuck Golden and at Mrs. Poliakov. That vision lasted until I heard her voice, deep and rough as a man’s. “Boy! You!”

She was standing on her top step, beckoning to me with an appropriately clawlike forefinger. For once she wasn’t wearing that weird tweed topcoat, but a long dark wool skirt and blouse that made her look like our idea of a gypsy. The old fedora covered her scanty white hair, giving substance to our belief that she wore it even in bed. She said it a second time. “You!”

I’d never heard her voice before. None of us had, as far as I ever knew. As long as she’d lived in that gray house, she must have yelled at two or three generations of children to stay out of her yard. By the time we came along, it wasn’t necessary anymore: the fear had been passed down to us with the legend, and however much we might mock her in private, she didn’t have to say a word to scatter us when she wanted to. Our parents, when they noticed, teased us for scaredy-cats, but we knew what we knew.

Now I walked slowly toward her, feeling my friends’ terror behind me, but unable to turn my head. I stopped at the bottom of Mrs. Poliakov’s front steps. She looked at me out of eyes so gray they were almost black, eyes younger than the drooping, wrinkled lids under which they studied me. The grating, heavily-accented voice—Russian, I think now, but maybe Polish—said, “You ball, boy?”

“Uh,” I said. “Uh, yes. My ball. Our ball.”

“That game,” Mrs. Poliakov said. “What game? Lapta?”

Oddly enough, I knew about lapta, because my mother was born in the Ukraine. Lapta involves a bat and ball, and a lot of running back and forth, but it’s more like cricket than baseball. I said, “No, no lapta. Stickball. Steeck-boll.”

Mrs. Poliakov said, “Steeck....” and then “Sticks... ball,” and about got it right. I nodded eagerly, “Stickball, that’s it, we play it all the time. We don’t mean to hit the balls into your yard, we’re really sorry....” My own voice gradually dried up as I stared into those old, gray, relentlessly clear eyes. “Can we... could we have our ball back now? Ball, okay?” and I held the rescued Spaldeen up, so she’d understand what I was talking about. “Ball?”

Quicker than I can say this, she snatched that ball back from me, holding it over her head as though she expected me to jump for it. “No, nyet, no ball,” and she pointed toward the street with her free hand. I thought she was telling me to get the hell out of her yard, but that wasn’t it either, nor was she throwing me out when she grabbed my arm and started walking with me, saying, “Game, hanh? Show—show me sticksball. You show.”

And here we came, the two of us, marching as to war, back into the street where my friends were standing gaping at us, some of them backing away from a scary old neighborhood witch, none of them with a word to say. She was enjoying herself—you could actually see it in the glint of her eyes, and in the way she limped over to J.T. Jones and slapped the Spaldeen into his hand. “Sticksball, okay, hanh? Show.”

I wonder less about how she guessed that J.T. was our pitcher than how she knew that we used a pitcher at all. Most teams didn’t: no matter how much the rules vary, block to block, in the majority of stickball games the batter just tosses the ball up himself and times his swing to its descent. But we always had a real pitcher, even though that meant our taking turns at catcher; even if he had to pitch for both sides, as he mostly did. And J.T. was good, even throwing underhand, and he was honest as well; never took anything off his pitches when we were at bat, which pissed some guys off, but most of us were proud of him. He was a legend, at least in the North Bronx. At least on Tryon Avenue, and all the way to Jerome on one side, and down to Webster the other way. Down to White Plains Road, really.

We chose up sides again and started a new game; but who could keep his mind on playing, with that woman who’d terrified us all our lives standing there watching, her hands behind her back and a very slight smile on her whiskery old lips? J.T.’s hands were so sweaty the ball kept getting away from him, and Miltie Mellinger kept losing the broomstick when he swung, for the same reason—almost nailed me one time, the stick flew straight at my head. We hit, all right, so much that keeping score quickly became pointless. J.T. wasn’t up to anything but just laying it in there, and even the weakest hitters like Howie Stern and Marv Cooper were slamming it over the parked cars and the green trees for the rest of us to run down. Not me, though: I struck out three or four times and slunk off to lean against Howie’s father’s Packard, which was our dugout. For all the scoring, nobody talked or cheered much, I remember that.

Mrs. Poliakov said “Hanh,” again, loudly, like a whale coming up to blow. She said, “Sticksball. Give me. Give.” She held out her hand.

J.T. looked around at everyone before he put the Spaldeen into her hand. Stewie Hauser said, “Okay, relief pitcher coming in, pop that glove, bubbe,” and crouched down to catch. Bubbe is grandma, but nobody laughed. Mrs. Poliako

v adjusted her fedora and turned the rubber ball slowly between the swollen-knuckled fingers of both hands, studying the Spalding logo intently for minutes before she looked up and repeated, “Okay.” She gestured to Marv to stand in, even though he wasn’t due up yet. He didn’t argue. Mrs. Poliakov gave an arthritic little hop, clumsily imitating J.T.’s motion, and she pitched.

Marv never saw it. I’m not sure Stewie did, either, until he was yelling “Jesus Christ, sonofabitch!” and sucking his fingers as the ball bounced away from him toward the sidewalk. J.T.’s mouth was open, and Richie Williams was actually crossing himself. Junius Dinkins was just saying softly, “Naww, man,” over and over. And Mrs. Poliakov beckoned, as she had beckoned to me in her front yard, and the Spaldeen came back to her.

It rolled meekly then; later on, it came bouncing jauntily as though it knew the way better. Mrs. Poliakov was an awkward fielder; anyone who even made contact would easily have been on base by the time she picked the ball up. But none of us ever did—J.T. managed a couple of trickling fouls, but that was it. The Spaldeen either came in so impossibly fast and hard that after a little we were bailing out before she released it; or else the thing simply zigzagged, dodged our bats, curved around us, dropped literally out of sight, or changed its pink-rubber mind and backed up in mid-flight. Satchel Paige messed with batters’ heads by warning and half-convincing them that he could make a baseball do all those things. Mrs. Poliakov was doing it, and doing it with a toy you could get at Lapin’s corner store for twenty-five cents, with tax; cheaper, you buy a dozen. I will always believe—and so, I promise you, will anyone else who was there—that she could have done exactly the same thing with a pair of rolled-up gym socks.

Stewie Hauser hadn’t stopped saying “Jesus Christ!” from that first pitch, and Miltie Mellinger kept mumbling, “It’s a trick, she does something to the ball, a spin.” Chuck Golden, who always had to know more than you did, was explaining learnedly, “She’s throwing a spitball, that’s illegal. My dad told me about spitballs.” Some of the girls jumping rope and pushing doll carriages had stopped playing, and were staring from the sidewalk; there were even one or two adult onlookers, who could tell that something was going on. We ourselves would have quit, if we could, but Mrs. Poliakov wouldn’t let us, not until she was good and ready. We’d have to keep dragging our broomsticks up there all night, if she wanted; through all eternity, if she chose. That we knew without a word.

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand Return

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

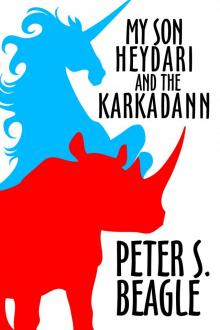

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

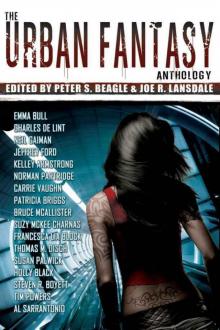

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

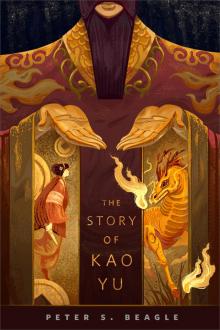

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

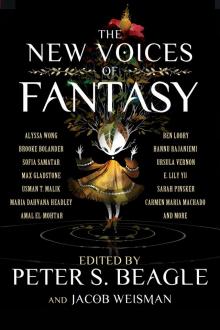

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

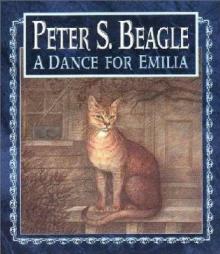

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song