- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

Innkeeper's Song Page 2

Innkeeper's Song Read online

Page 2

When they rode into my courtyard, I came out—I’d been polishing glass and crockery myself, since there’s no one else to trust with it around this place—took one good look at them and said, “We’re full up, stables, everything, sorry.” As I told you, I am neither brave nor greedy, merely a man who has kept house for strangers all his life.

The black one smiled at me. She said, “I an told otherwise.” I have heard such an accent before, very long ago, and there are two oceans between my door and the country where people speak like that. The boy slid down from her saddle, keeping the horse between us, as well he might. The black woman said, “We need only one room. We have money.”

I did not doubt that, journey-fouled and frayed as all three of them looked—any innkeeper worth his living knows such things without thinking, as he knows trouble when it comes asking to sleep under his roof and eat his mutton. Besides, the boy had made a liar of me, and I am a stubborn man. I said, “We have some empty rooms, yes, but they are unfit for you, the rains got into the walls last winter. Try the convent, or go on into town, you’ll have your choice of a dozen inns.” Whatever you think of me, hearing this, I was right to lie, and I would do it again.

But I would do it better a second time. The black woman still smiled, but her hands, as though twitching nervously, fidgeted at the long cane she carried across her saddle. Rosewood, very handsome, we make nothing like that in this country. The curved handle twisted a quarter-turn, and a quarter-inch of steel winked cheerfully at me. She never glanced down, saying only, “We will take whatever you have.”

Aye, and didn’t that prove true enough, though? The swordcane was the end of the matter, of course, but I tried once again; to save my honesty, in a way, though you won’t understand that. “The stables wouldn’t suit a sheknath,” I told her. “Leaky roof, damp straw. I’d be ashamed to put horses as fine as yours in those stalls.”

I cannot recall her answer—not that it makes the least difference—first, because I was looking hard at that boy, daring him to say other and second, because in the next moment the fox had wriggled out of the brown woman’s saddlebag, leaped to the ground and was on his way due north with a setting hen by the neck. I roared, imbecile dogs and servants came running, the boy gave chase as hotly as if he hadn’t personally brought that animal here to kill my chicken, and for the next few moments there was a great deal of useless dust and clamor raised in the courtyard. The white woman’s horse almost threw her, I remember that.

The boy had the stomach to come sneaking back, I’ll say that much for him. The brown woman said, “I am sorry about the hen. I will pay you.” Her voice was lighter than the black woman’s, smoother, with a glide and a sidestep to it. South-country, but not born there. I said, “You’re right about that. That was a young hen, worth twenty coppers in any market.” Too much by a third, but you have to do that, or they won’t respect a thing you own. Besides, I thought I saw a way out of this whole stupid business. I told her, “If I see that fox again, I’ll kill it. I don’t care if it’s a pet, so was my hen.” Well, Marinesha was fond of it, at least. They suited each other nicely, those two.

The brown woman looked flustered and angry, and I was hopeful that they might just throw those twenty coppers in my face and ride on, taking their dangers with them. But the black one said, still toying with that sword-cane without once looking at it, “You will not see it again, I promise you that. Now we would like to see our room.”

So there was nothing for it, after all. The boy led their horses away, and Gatti Jinni—Gatti Milk-Eye, the children call him that—my porter, he took in what baggage they had, and I led them to the second-floor room that I mainly keep for tanners and fur traders. I already knew I wouldn’t get away with it, and as soon as the black one raised an eyebrow I took them on to the room where what’s-her-name from Tazinara practiced her trade for a season. Contrast, you see; most people jump at it after that other one. Swear on your gods that you practice no such sleights, and that dinner’s a gift, fair enough?

Well, the black woman and the brown looked around the room and then looked at me, but what they had it in mind to say, I never knew, because by then the white one was at me—and I mean at me, you understand, like that fox after the broody hen. She hadn’t said a word since the three of them arrived, except to quiet that jumpy horse of hers. Up until then, I could have told you nothing about her but that she wore an emerald ring and sat her saddle as though she were far more used to riding bareback on a plowhorse. But now, quicker than that fox—at least I saw the fox move—she was a foot away from me, whispering like fire, saying, “There is death in this room, death and madness and death again. How dare you bring us here to sleep?” Her eyes were earth-brown, plain peasant eyes like my mother’s, like most of the eyes I ever saw. Very strange they always looked to me, that pale, pale face burning around them.

Mad as a durli in the whistling time, of course. I won’t say that I was frightened of her, exactly, but I certainly was afraid of what she knew and how she knew it. The Gaff and Slasher had a bad name before I bought it, just because of a killing in that same room—and another in the wine cellar, for the matter of that. And yes, there was some bad business when the woman from Tazinara had the room. One of her customers, a young soldier it was, went lunatic—came there lunatic, if you ask me—and tried to murder her with a crossbow. Missed her at point-blank range, jumped out the window and broke his idiot neck. Yes, of course, you know the story, like everyone else in three districts—how else could fat Karsh have bought the place so cheaply?—but this pale child’s voice came from the south, maybe Grannach Harbor, maybe not, and in any case she could not possibly have known which room it was. She could not have known the room.

“That was long ago,” I said back to her, “and the entire inn has been shriven and cleansed and shriven again since then.” Nor did I say it as obsequiously as I might have, thinking about the cost of those whining, shrilling priests. Took me a good two years to get the stink of all their rackety little gods out of the drapes and bedsheets. And if I had had the sense of a bedbug, I could likely have gotten rid of those women then, standing on my indignation and injury—but no, I said I was a stubborn man and it takes me in strange ways sometimes. I told them, “You can have my own room, if it pleases you. I can see that you are ladies accustomed to the best any lodging-house has to offer, and will not mind the higher price. I will sleep here, as I have often done before.”

Silly spite, that last—I dislike the room myself, and would sooner sleep with the potatoes or the firewood. But there, that is what I said. The white one might have spoken again, but the brown woman touched her arm gently, and the black woman said, “That will do, I am sure.” When I looked past her, I saw the boy in the doorway, gaping like a baby bird. I threw a candlestick at him— caught him, too—and chased him down the stairs.

TIKAT

On the ninth day, I began to starve. I had taken far too little food with me. How could I not have, sure as I was of catching up by first sunset and making that black woman give me back my Lukassa? Amazed I am to this day that I even thought to bring a blanket for the chill when we would be riding so happily home together. As long as she lay in the water, she will be frozen to her poor heart. That is all I was thinking, all, for nine days.

And of course I know now that it would have made no difference if I had stopped to steal a dozen horses—as though there were that many in the village—and load them to backbreak with food and water and clothing. For I never caught up with those two women, never drew within half a day’s ride, though my mare broke her own brave heart in trying. They were never closer than the horizon, never larger than my thumb, never any more solid than the chimney smoke from the towns they skirted. Now and then I crossed the remains of a campfire—carefully scattered—so they must have slept sometimes; but whether I rested or galloped all night, they were always far beyond my sight come dawn, and not before midday would I catch the least movement on the side of the furthest h

ill, the twitch of a shadow among stones so distant that they looked like water across the road. I have never been so lonely.

There’s this about starving, though, it takes your mind off things like loneliness and sorrow. It hurts very much at first, but soon you start to dream, and those are kind dreams, perhaps the sweetest I ever had They weren’t always about food and drink, either, as you’d suppose—most often I was old and home with my girl, children close and my arm so tight around her when the bridge railing broke that she still bore the mark all those years later. I dreamed about my father, too, and my teacher who was his teacher, and I dreamed I was little, sitting in a pile of sawdust and wood shavings, playing with a dead mouse. They were very dear dreams, all of them, and I tried harder and harder not to wake.

I don’t remember when I first noticed the tracks of the second horse. The ground was hard and stony, and growing worse and I often went a day or longer finding nothing but a hoofscratch or two on a displaced pebble But it must have been some little time after the dreams began, because I laughed and cried with pleasure to think that Lukassa would at last have a horse of her own to ride When we were children, she made me promise one day to buy her a real lady’s horse, none of your plough-beasts that might as well be oxen, but some dainty, dancy creature, as far beyond my reach then as now, and likely as useless in our life together as bangles on a hog. But I swore my word to her—so small a request it seemed, when she could have had my eyes for the asking. Seven we were, or eight, and I loved her even then.

If I had been in my right mind, surely I would have wondered where that second horse had come from in this empty country, and whether it truly bore Lukassa or another. A woman who had sung my girl up from the river bottom could summon a horse as easily, like enough; but why now, as far as they had come on the one, and tireless as he plainly was? But by then I was walking as much as riding, hanging on my mare’s sagging neck, pleading with her not to die, to live only a little longer, half a day, half a mile. You couldn’t have told which of us was dragging the other, and I couldn’t have told you, for I was swimming in the air, laughing at jokes the stones told me. Sometimes there were animals—great pale snakes, children with birds’ faces—sometimes not. Sometimes, when the black woman was not looking, Lukassa rode on my shoulders.

On the eleventh day, or the twelfth, or perhaps the fifteenth, my mare died under me. I felt her die, and managed to sprawl clear to keep from being crushed by her bones. If I had been strong enough to bury her, I would have done it; as it was, I tried to eat her, but I lacked even the strength to cut through her hide. So I thanked her, and asked her forgiveness, and the first bird that laid claw on her I fell on and strangled. It tasted like bloody dust, but I sat there beside her, chewing and growling in full sight of the other birds. They left her alone for a while, even after I walked away.

The bird sustained me for two more days, and cleared my mind enough at least to realize where I must be. The Northern Barrens, no desert, but almost as bad. As far as you can see, the land is broken to pieces, everything smashed or split or standing on edge. Here’s a toss of boulders blocking the way, the smallest bulking higher than a man on horseback; here’s a riverbed so long dry there are wrinkled little trees growing up out of it; there, all that tumble and ruin might have been a mountain once, before great claws ripped it down. No road, never so much as a cart track—if you have all your wits about you, you pick your way across this country, praying to the gods’ gods not to break a leg or fall in a hole forever. Starving mad like me, you stagger along singing, peaceful and fearless. I dreamed my death, and it kept me safe.

There was an old man in one of those dreams. He had bright gray eyes and a white mustache, curling into his mouth at the corners, and he wore a faded scarlet coat that might have been a soldier’s. In my dream he came galloping on a black horse, crouched so far forward that his cheek lay almost against the horse’s cheek, and I could hear him whispering to it. For a moment, as they flashed by me, the old man looked straight into my face. In his eyes I saw such laughter as I never expect to see again while I live. It woke me, that laughter, it brought me back to the pain of being about to die alone in the Barrens, without Lukassa, and I fell down weeping and screaming after that old man until I slept again, truly slept, on all fours like a baby. I dreamed that other horses passed, with great hounds riding them.

When I wakened, the sun was dropping low, the sky turning thick and soft, and the least breeze rising. The sleep and the hope of rain made me feel stronger, and I went on until I came to a place where the ground sloped down and in on all sides: not a valley, just a stony dimple with a stagnant pool at the bottom. They were down there, the hounds, and they had taken prey.

There were four of them, Mildasis by their daggers and their short hair. I had only seen Mildasis twice before— they come south but seldom, which is good. They had the old man in the scarlet coat between them and were buffeting him round and round, knocking him savagely from one to the other until his eyes rolled up in his head and he could not stand. Then they kicked him back and forth, like the ragged ball he rolled himself into, all the while cursing him and telling him there were worse pains waiting for a man insanely foolish enough to steal a Mildasi horse. Not that I know two words of Mildasi, but their gestures made things quite clear. The horse in question stood loose nearby, reins hanging, pawing for thistles among the stones. It was a shaggy little black, almost a pony, the kind the Mildasis say they have been breeding for a thousand years. They eat whatever grows, and keep running.

The Mildasis did not see me. I stood behind a rock, bracing myself against it, trying to think. I was sorry for the old man, but my pity seemed as quiet and faraway as all the rest of my feelings, even the hunger, even the understanding that I was dying. But my horse was already dead, and there were the four other Mildasi horses, waiting untethered like the black, and I did know that I needed one of those, because there was a place I had to go. I could not remember the place, or why I had to be there, but it was very important, more important than starving. So I made the best plan I could, watching the Mildasis and the old man and the setting sun.

I know about the Mildasis what everybody knows—that they roam and raid out of the barren lands, never surrender, and value their horses more than themselves—and perhaps one thing more, which my uncle Vyan told me. He had traveled with caravans when he was young, and he said that the Mildasis were a religious people in their way. They believe that the sun is a god, and they do not trust him to return every morning without a bribe of blood. Usually they sacrifice one of the beasts they raise for that purpose, but the god likes human blood much better, and they give it to him when they can. If my uncle was right, they would kill the old man just as the sun touched the furthest hills. I moved around the rock slowly, like a shadow stretching in the sun.

The horses watched me, but they made no sound, even when I was very close to them. I am not wise with horses, like some—I think it was my madness that made them take me for a friend, a cousin. Uncle Vyan said that Mildasi horses were more like dogs, loyal and sometimes fierce, not easy to frighten. I wanted to pray that he was wrong about that, but I had no room for prayer. The Mildasis had their backs to me, making ready for the sacrifice. They were not beating the old man anymore, or even mocking him—they seemed as serious as either of the priests in our village when they blessed a baby or begged for rain. First they smeared his cheeks with something yellow, then made marks in it with their fingers, so carefully. They made his mouth black with something else.

He stood quite still, not speaking, not struggling. One of the Mildasis was singing, a high, scraping song that quavered as though he were the one about to be killed. The same few notes, over and over. When he stopped singing, there was no more than a breath of wind between the sun and the hilltops.

The Mildasi who sang took a long knife from another one. He showed it to the old man, making him study it, pointing at the blade, handle, the blade again, like my teacher trying to make m

e understand the real life of a pattern. I would know that knife if I ever saw it again.

The horse I had chosen hours, days ago was gray, like a rabbit. He let me touch him. The Mildasi began to sing again, and I was up on the gray horse, shouting and waving my arms to terrify the others. They looked surprised, a little disappointed in me; they danced on their hind legs and glanced toward their masters, who were only now turning, gaping, as silently astonished as the horses, but two with their throwing axes already out. The Mildasis can bring down nightbirds with those, my uncle Vyan says.

It was the black horse who suddenly decided to be frightened, to rear and scream and bolt, knocking down the singing Mildasi and trampling the knife-man, who rushed in to help him. The two others jumped for the reins, but the black dashed past them, heading for the comfort of its friends. But now they caught the panic themselves, as though it were a torch bound to the black, setting their tails afire. My gray—the Rabbit, as I called him from that day—went up in the air, all four feet off the ground, and came down out of my control, running straight back toward the two Mildasis who barred the way, axes whirling red in their hands. I flattened myself along the Rabbit’s back, clutching him as I had held Lukassa in the river. I could not see the old man.

One axe sighed past my nose, taking nothing with it but a hank of gray mane. The second I never saw at all, but the poor Rabbit yelled to break your heart and shot away in a different course, as rabbits will do. The tip of his right ear was gone, blood spraying back on my hands.

I looked back once, in time to see all four Mildasis—two of them limping—scrambling madly after their horses, and those in no hurry at all to be sane and obedient ever again. Then, with my head still turned, a hand on the saddle, a hand in my belt, a grunt and a wheeze and me almost spilled to the ground, and the old man was up behind me, laughing like the wind. “Ride, boy,” he barked in my ear, “ride now!” and I felt him turn to shout back at the Mildasis, “Fools, imbecile children, to think you could kill me! Because I chose to play with you a while, to think you had me—” The Rabbit flew over a narrow ravine then, and the old man yelped and clung to me, never finished his brag, which suited me just as well. If he would only be silent, perhaps I could pretend that he was not really there.

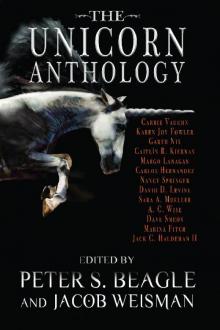

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

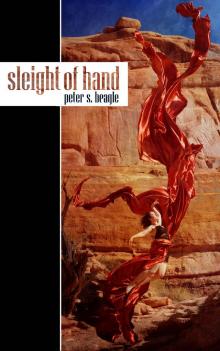

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

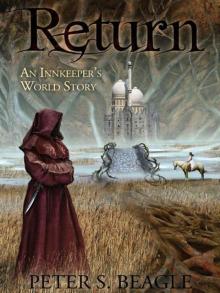

Sleight of Hand Return

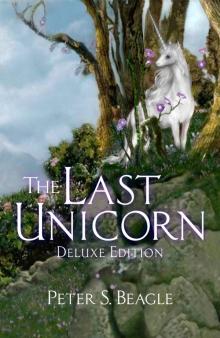

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

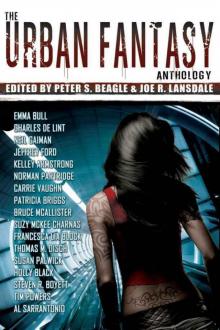

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

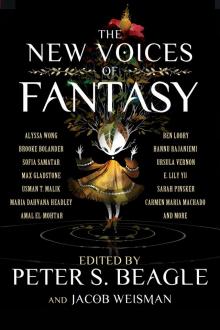

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song