- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

The Folk Of The Air Page 27

The Folk Of The Air Read online

Page 27

But the stair led down, and somehow sideways, as often as up, catwalk-narrow, alarmingly damp and skittery under his feet. He had given up trying to orient himself in relation to the house he knew; the one certain thing was that the disquieting sense of pressure was growing stronger, whether he climbed or descended. Beginning as a slow closeness in his head, it seemed now to be tightening on the house itself, clenching methodically, until Farrell could hardly move forward through the bell-jar silence. If he stood still for too long, Briseis came back for him, nudging and growling him along the stairway toward what looked at first like a distant street sign, then like the moon, and then like a door with light on the other side, which it was. It opened to Briseis’ gasping whine, and the two of them fell through it into afternoon and breath and the presence of Sia, who said, “Thank you, Briseis. You did very well.”

She sat in the middle of a pleasant, unexceptional room, in a chair that curled under and around her, its contours altering as she shifted her position. She wore a garment that he had never seen before; night-blue, night-silver, it drifted over her body like the shadow of a cloud, touching her as if it knew her. It flattered nothing, outlining her thick stomach and legs uncompromisingly, but Farrell bowed to her as he had bowed to Kannon herself. A voice that only long-senile Father Krone might have recognized said somewhere, “Great Queen of Heaven.”

“Don’t be stupid,” she answered him impatiently. “I am no queen—no more, never again—and there is no heaven, not the way you mean. And as for greatness—” When she smiled, her face appeared to break and flow with light. “—I sent Briseis to bring you here because I was lonely. Very tired, too, and very frightened, but mostly lonely. Do you think a great queen would do that?”

“I don’t know,” Farrell said. “I never knew any before.” The room might have been the parlor of a country inn, without the moose head and the piano; there were a couple of bookcases, a couple of dusty steel engravings, a worn but genuine Turkish rug, wallpaper patterned with sepia mermaids and gray sailors. Farrell asked, “What place is this? Where are we now?”

“This is a room where I was quite happy once,” she said. “Not the same room, of course, that one is gone, but I made it again, as well as I could, for myself. Sometimes this is all I have.”

“It’s not part of the house,” Farrell said.

Her quick headshake ended as a shrug. “Well, it is and then it isn’t. It is not exactly in the same place as my house, but it is as much a part of the house as anything else is. Only it is hard to find, even for me. I have spent weeks this last time trying to remember the way back. Briseis was really very clever, and you, too.”

“Has Ben ever been here?” She did not answer, and Farrell moved toward the two windows on either side of the still life of apples and wine bottles. Behind him, Sia said, “Be careful. Those windows are my eyes, in a way, and I cannot protect you from seeing what I see. Maybe you should not look out.”

There was a castle on the hot, shivering horizon, very far away across wide fields of barley and corn, bounded and traversed by yellow oxcart ruts. The castle was transparent at that distance and looked like sharp soap bubbles. Farrell stepped back, blinking, and the vision vanished, to be replaced by a flowering amber city whose structures made Farrell dizzy and cold to see; and in turn by a tiny three-cornered house tipped far out over a jungle river, where it shone and trembled before dawn. Fish swam through its walls.

“Oh,” he said. “How lovely.” As if his breath had scattered them, house, dawn, and river were gone, and once again he peered down on barley fields, footpaths and widecurving streams under a sky like a single pale-golden petal. He saw not castles this time, nor any great manors; and he might easily have overlooked the reed and turf thatches of the little mud-walled huts, except that, as he watched, these ruffled into fire, one after another, opening like waking birds. There were riders galloping past the huts, and men running between them with torches.

He widened his eyes until they hurt to make the scene disappear, but it became steadily more real. Where the riders had already passed, what he had taken for afternoon shadows were black and broken fields; rings of bright flowers resolved into the embers of homes; and everywhere the true shadows sheltered naked children cradling the split, spitted, riddled bodies of other children. Farrell saw a cow trudging in a widening circle of her own entrails, and he saw a woman gnawing eagerly on her arm, while an old man stared straight up into his face can he see me? with his mouth opening wider and wider. The old man turned deliberately, then dropped his breeches and bent over, exposing speckled, caved-in buttocks to Farrell’s gaze. Turning again, his mouth closed now, he gripped his penis in both hands and urinated shakily at the empty golden sky. The wind tossed the spray back at him, and it dribbled down his cheeks, mingling with his dirty tears.

Farrell whispered, “Make it stop,” and, blessedly, the vision began slowly to dissolve. His last sight of the country far below was of a fat woman running, carrying a cat and a feather bolster in her arms. The horseman coming after her was singing a song that Farrell knew.

“Who are you?” he cried out to Sia, and heard her answer inside himself.

“I am a black stone, the size of a kitchen stove. They wash me in the stream every summer and sing over me. I am skulls and cocks, spring rain and the blood of the bull. Virgins lie with strangers in my name, the young priests throw pieces of themselves at my stone feet. I am white corn, and the wind in the corn, and the earth whereof the corn stands up, and the blind worms rolled in an oozy ball of love at the corn’s roots. I am rut and flood and honeybees. Since you ask.”

The last words were spoken aloud, and, when Farrell could look at her, she was laughing, the Sia of the first morning, pumpkin-plump and cougar-quick, her gray eyes shining with ancient havoc. But this was not the first morning, and he demanded furiously, “Who are you? To show me that and laugh—I thought you were wonderful, I thought you were like her.” Her laughter moved in the parlor floor under Farrell’s feet.

“Like the Lady Kannon? Is that what you thought, that I was a goddess of mercy with a thousand arms, to save a world with each one? No, no, the Lady Kannon really is a queen, and I really am only a black stone. That was my first nature, and I have not changed so much.” But the mockery faded from her voice as she regarded him, and she added, “Not as much as perhaps I would have liked. I am stone that has washed dishes, slept in human beds, seen too many movies, but I am still stone. Stone can never be wonderful, I’m afraid.”

“Was it real, what I saw? Where was it real?” She did not bother to reply. “There was a woman running,” he said. “You could have helped her, anyway. There were so many children.”

“I told you, I am not Kannon.” The silver ring that held her hair stirred against her cheek, glinting like a tear. She said, “What I did for your friend I did because the thing that had happened to him was against certain laws, as what you saw from my window is not. And even for that, I needed help myself, and I could not have summoned it without that girl, your Julie. I have no power beyond this house—perhaps not beyond this room now.”

Briseis whimpered and skulked close to her, clearly not daring either to push for comfort or offer it, but collapsing again within comfort’s range, just in case. Farrell said, “Well. I wish I could have seen you when you were a black stone.”

“Oh, I was certainly something.” The tone was sardonic enough, but her voice was gentle in that moment. She said, “It was nice, I think, the flutes and the smoky prayers and the screaming—a long time ago, that must have been what pleased me. I intervened everywhere, absolutely everywhere, in everything, just to be doing it, just because I could.” Her bitter chuckle prickled his skin, as his own music did. “I would have been more use to those children if I had remained all stone.”

“I don’t understand,” he said. “I don’t understand how a goddess can lose her power.”

She drew back slightly, looking at him with a kind of dangerous wonder, be

fore she smiled. “Oh, very good. I never thought you would ever use that word. Well, with power it is the same for everyone—if you don’t want it quite enough, it just leaves you. Power always knows, you see. And gods always lose their power, because we lose our pleasure in it, we all come to want other things, sooner or later. This is where we are different from human beings.”

“What did you want?” Farrell asked. “What was it you wanted more than being a goddess?” Sia slipped the silver ring off and began slowly to unweave her thick, straggly braid, as she had done on the night she tried to bend the universe for Micah Willows. Farrell thought, It’s the opposite of that thing the Finnish sailors do. They tie up the winds with bits of string, they tie magic into knots. She’s turning it loose, and I’m watching her.

“Brush my hair, please,” she said, “Ben forgot last night. The brush is on that little table.

So Farrell stood behind her strange, flowing chair, in a room that did not exist, and he brushed her hair, as he had always wanted to do, feeling the black and gray sea-weight of it murmur and burn over his hands, feeling the freed winds stretching themselves like cats waking to hunt. Once, showing him how to use the brush correctly, she touched his face, and he remembered lying all one day in a summer meadow, watching a Monarch butterfly being born.

“I like it here,” she said softly. “Of all worlds, this one was made for me, with its silliness and its cruelty, and its fine trees. Nothing ever changes. For every understanding, a new terror—for each foolishness at last pulled down, three little new insanities sprouting. Such mess, such beauty, such hopelessness. I talk to my clients, but I can never know how they can get up in the morning, how any of you can even get out of bed. One day, nobody will bother.” She put her head further back, closing her eyes, as he continued brushing; and he saw how, with the small coquettish movement, the ruts and flutings of her throat at once softened and tautened, like stream beds under the first rain of the season. Her hair breathed calmly now between his hands.

“And still you desire one another,” she said. “And still you invent and reinvent yourselves, you manufacture entire universes, just as real and fatal as this one, all for an excuse to stumble against one another for a moment. I know gods who have come into existence only because two of you wanted there to be a reason for what they were about to do that afternoon. Listen, I tell you that on the stars they can smell your desire—there are ears of a shape you have no word for listening to your dreams and lies, tears and gruntings. There is nothing like you anywhere among all the stones in the sky, do you realize that? You are the wonder of the cosmos, possibly for embarrassing reasons, but anyway a wonder. You are the home of hunger and boredom, and I roll in you like a dog.”

Abruptly she turned, took hard hold of his shoulders, and kissed him on the mouth, pulling herself to her feet as she did so. Farrell, who had wondered often enough what that could be like and flinched slightly in his imagination from the muscular contact, dry as cast snakeskin, found that her breath was noisy and curious and full of flowers, and that kissing her was as shocking and undoing a revelation as the first chocolate he had ever tasted. The chair purred under them, pouring itself across the floor. Farrell sank through the night-colored gown to swim in Sia’s absolute welcome with the frightened ease and eagerness of the small fourhanded land creature that remembered the sea and became the grandfather of whales. Her breasts were as softly shapeless as he had supposed, her belly as mottled; and Farrell kissed and prowled her, laughing as she did in bedazzlement at such bounty until she put her arms around his neck and told him, “Now look at me, now don’t stop looking at me.” That became quickly hard to do, but they held tightly to each other, and Farrell never looked away from her, even when he saw the black stone and what lay before it. He only closed his eyes at the last, when her face became too beautiful and sorrowful to bear. But she smiled straight into his head like someone else, and all his bones went up in sunlight.

As soon as he could speak, he said, “Nicholas Bonner is your son.” They were still joined, still shivering, sprawled together like sacrifices; and she was silent for so long that he was dozing a little when she answered him. “Sleep with a mortal and lose your secrets. Ben wakes up each morning knowing one more thing that I did not tell him.”

“Oh, lord,” Farrell said. “Ben. Oh, Ben. Oh, no wonder he looks like that.”

He began touching his face and peering down along himself, while Sia laughed at him, saying “Don’t be an idiot.” Let me remember this, please, when everything else goes let me remember a goddess laughing after love. She said, “You have not changed. I am not a virus, you haven’t caught me. For that you would have to enter my life, as Ben has, you would have to be exposed.” She slipped away from him and sat up, hugging her knees. “Nicholas Bonner is my son, yes, or at least that was the idea. No, there is no father, none at all. Is there anything else you would like to know?”

“I would dearly like to know why you still have clothes on and I don’t.” The blue-and-silver garment had no buttons, no zippers, no least stain or rumple. He said, “I never saw you put that thing back on.”

“It was never off. Mortals should not see the gods naked, it’s very dangerous. No, you didn’t see me, Joe, you were overexcited. Be quiet and listen.” The chair stood up with her, dumping Farrell to the floor as he began gathering his clothes. He kissed her foot as it went by toward the windows. Briseis came and sniffed at him, neither wagging nor whining. He said to her, “We will talk about this later.”

Sia said, “I was lonely. It is an occupational hazard for us, and we deal with it in different ways. Some gods create worlds, entire galaxies, just to have someone intelligent and sympathetic to talk to. They are usually disappointed. Others go in for having children—they mate with each other, with humans, animals, trees, oceans, even with the elements. It is all very exhausting and takes up most of their time. But they do have the children in the end. Some of them have thousands.”

“And, would you believe it, not one of the little bastards ever writes?” Sia looked at him, and he said, “Sorry. I don’t know how Ben is at such moments, but I feel like Central Park, or a birdbath or something. So. You wanted a child.”

“I am not sure what I wanted anymore. It was long ago, and I was different. Your world existed, I remember that, but it was all fire and water then, nothing else. I had no idea that I would come to love it so much.” She paused for a moment. “We have no word for love, you know. Hunger, degrees of hunger, that is as close as we can come. If you were a god, we would have been making hunger together.”

“So you had Nicholas Bonner,” Farrell said gently. “Conceived in hunger, out of loneliness. Does he know he’s your son?”

“He knows I did not have him,” she said. “He knows I made him. Do you understand me?” Her voice was as sad and cruel as wind crawling around the corners of a house. “What he knows is that I made him in myself, by myself, not even really out of loneliness, but out of contempt, such contempt for mysteries, oracles, temples, all those warrens of little half-gods and quarter-gods, that helpless vampire need that illusions have for adoration. I was going to make a child who could exist without fraudulence, who would be a god if nothing in the universe ever worshiped him. Contempt and vanity, you see. Even for a goddess, I have always been vain.”

Farrell wanted to go to her as she stood at the window with her back to him, but, like Briseis, he dared not cross the border of her pain. He said only, “Well, he scares the pure hell out of me, but he’s not a god. Not if you are.”

“He is not anything. You cannot make anything useful out of contempt and vanity, no matter who you are. Nicholas Bonner is not a god, not human, not a spirit of power—he is nothing, nothing but immortal and eternally enraged at me. As he should be. Can you begin to imagine what I did to him?” She turned to look at Farrell, and her face was gray and small. “Can you imagine what it might be like to know certainly that you have no business existing anywhere—that there is no

possible place for you from one end of the universe to the other? Can you imagine how that would feel, Joe? Knowing that you can never even die and be free of this terrible not-life, never? That is what I did to my son, Nicholas Bonner.”

Farrell said, “You must have tried to—l don’t know—to unmake him. You were stronger then, you must have tried.”

Sia nodded impatiently. “I could not do it, I was never strong enough. I was exactly like your little witch, just playing with power for every wrong reason and stumbling onto something that would take a miracle to undo. The most I have ever been able to do is to send him very far away, to a place you might call limbo. I don’t want to talk about it. There is nothing to do there but try to sleep and wait for someone to summon you by mistake. Someone always does.” She chuckled suddenly, grimly, and added, “He always looks like that, by the way. My bodies all seem to be older and uglier each time, but Nicholas Bonner is fourteen years old forever.”

“He hates it there,” Farrell said, remembering that first long cry of terror in the redwood grove: Hither then, swiftly, for I’m cold, I’m cold. Sia nodded, looking away. Farrell said, “Something is squeezing this house like a nutcracker. I can’t feel it here, but everywhere else. What’s going on?”

“It has begun.” Her voice was placid, almost indifferent. “In time, maybe a few days, they will try again to come into my house, and he will try to make me go to that place where I have sent him before. I wonder if the girl is strong enough to enter this room. The house, yes, I think so, but perhaps not here.” She took Farrell’s hand between her square, stubby-fingered ones, smiling at him, but not drawing him across the invisible line. She said, “Joe, goodness, don’t look that way. There is nothing Nicholas Bonner can do but destroy me for the sake of some justice. The dreadful thing is that it is all he can do.”

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand Return

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

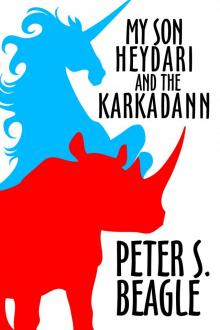

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

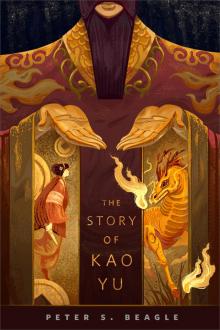

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

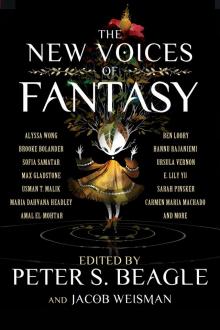

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

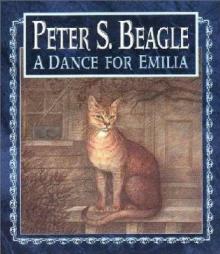

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song