- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

The Folk Of The Air Page 3

The Folk Of The Air Read online

Page 3

“Ah, it’s just a scratch,” he said. “I always wanted a chance to say that.” But Sia was beside him, rolling up his sleeve, although he protested earnestly, “Farrell’s Fifth Law: If you don’t look at it, it doesn’t hurt as much.” The wound was a long, shallow gouge, clean and uncomplicated, looking like nothing but what it was. He told her about Pierce/Harlow, carefully spinning the whole unlikely event into a harmless, idiotic tall tale, while she washed his arm and then drew the cut closed with butterfly bandages. The more he tried to make her laugh, the more tense and abrupt her hands became on him; whether with sympathy, apprehension or only contempt for his foolishness, he could not tell. He chattered on, helplessly compulsive, until she finished and stood up, muttering to herself like any ruinous ragbag lost in a doorway. Farrell thought at first that she was speaking in Greek.

“What?” he asked. “Should have known what?” When she turned to face him he realized in bewilderment that she was furious at herself, this odd, sly, squat woman, as intensely and unforgivingly as though Pierce/Harlow were her personal responsibility, the holdup all her own absentminded doing. The gray eyes had darkened to the color of asphalt, and the airy morning kitchen smelled like a distant storm. She said, “It is my house. I should have known.”

“Known what?” he demanded again. “That I’d shove my arm onto some preppy bandit’s knife? I didn’t know it myself, how could you?” But she stood shaking her head, looking down at Briseis, who crouched and whined. “Not outside,” she said to the dog. “No more, that is gone. But this is my house.” The first words had fallen as softly as leaves; the last hissed like sleet. “This is my house,” she said.

Farrell said, “We were talking about Ben. About his really being older than you. We were just talking about that.” It seemed to him that he could feel her anger crowding the silence, see it piling up around them both in great drifts and ranges of static electricity. She stared at him, squinting as though he were drawing steadily away from her, and finally showed small white teeth in a cold sigh of laughter.

“He likes me to be old and wicked and clever,” she said. “He likes that. But I feel sometimes like a—what?—like a witch, like a troll queen, one who has enchanted a young knight to be her lover, but he must never hear a certain word spoken. It is nothing magic, just a word out of the kitchen or the stables—but if he hears it, it is all up, he will leave her. Think how she would guard him, not from magicians, but from horseboys, not from beautiful princesses, but from cooks. And what could she do? And whatever she did, how long could it be? Someone would come along and say straw or dishrag to him sooner or later. And what could she do?”

Farrell flexed his arm cautiously and reached a second time to touch his lute. “Not much. I suppose she’d just have to go on being a queen. There’s a shortage of queens these days, trolls or any other kind. People are complaining about it.”

She laughed so that he could hear it then, the slow, disheveled laugh of a human woman in the morning; and suddenly they were only themselves at the table, and nothing in the kitchen but sunlight and a dog and the smell of cinnamon coffee. “Play for me,” she said, and he played a little, sitting there: some Dowland, some Rosseter. Then she wanted to know about his wanderings, and they talked quietly of freighters and fishing boats, markets and carnivals, languages and police. He had lived in more places than Sia, but never as long; he had been to Syros, the island of her birth, that she had not seen since girlhood. She said, “You were Ben’s legend for a long time, you know. You acted things out for him.”

“Oh, everybody has one of those,” he answered. “People’s dreams dovetail like that. My own legend was running around Malaysia on a bicycle, the last I heard of her.”

The mischief flared again in Sia’s eyes. “But what a strange sort of Odysseus you are,” she said. “You keep having the same adventure over and over.” Farrell blinked at her uneasily. Sia said, “I have read your letters to Ben. Wherever you wake up and find yourself, you take some stupid job, you make a few very colorful acquaintances, you play your music, and sometimes, for one letter, there is a woman. And then you wake up somewhere else, and it all begins again. Do you like such a life?”

In time he learned almost to take it for granted, that moment in a conversation with Sia when the ground under his feet was gently gone, like a missed stair or curbstone, and he invariably lurched off-balance, as violently as when he twitched out of a falling dream. But just then he felt himself blushing, saying with hot flatness, “I do what I do. It suits me.”

“Yes? How sad.” She got up to put the dishes in the sink. She was still laughing to herself. “I think you allow yourself only the crusts of your experiences,” she said, “only the shadows. You always leave the good part.”

The lute breathed like a creature waking slowly as he picked it up. “This is the good part,” he said. He began to play a Narvaez pavane that he was vastly proud of having transcribed for the lute. The translucent chords fell slowly, shivering and sliding away through his fingers. Ben came in while he was playing, and they nodded at each other, but Farrell went on with the pavane until it ended abruptly in a gentle broken arpeggio. Then he put the lute down, and he got up and hugged Ben.

“Spanish baroque,” he said. “I’ve been playing a lot of it, the last year or so.” Ben put his hands on Farrell’s shoulders and shook him slowly but hard. Farrell said, “You look different.”

“You don’t look any different at all,” Ben said. “Except the eyes.” Sia sat watching them, one hand closed in Briseis’ fur.

“That’s funny,” Farrell said softly. “Your eyes haven’t changed.” He stared, wary and fascinated and truly alarmed. The Ben Kassoy with whom he had waited for buses in the New York morning snow had looked very much like a dolphin and moved as sweetly and frivolously as any dolphin through the acrid waters of the high-school pool. On land he had tripped over things, tall and slouching, nearsighted, stranded in this stingy, unkind element. But he carried himself with Sia’s fierce containment now, and the glassy skin had weathered to the hard opacity of sailcloth, the round, blinking face—dolphin-browed, dolphin-beaky, dolphin-naked of shadows—grown as rough and solitary and rich with darknesses as a Crusader castle. Farrell had been casually prepared, after seven years, for a cleared-up complexion and the first gray hairs; but he would have passed this face in the street, turning a block later to look after it in wonder and disbelief. Then Ben knuckled his mouth with his left forefinger in the old study-hall habit, and Farrell said automatically, “Don’t do that. Your mother hates that.”

“As long as you crack your toes in class, I can chew my finger,” Ben said. Sia came silently to stand beside him, and Ben put an arm around her shoulders. He said to her, “This is my friend Joe. He takes his shoes off under the desk and does terrible things with his feet.” Then he looked at Farrell and kissed her, and she moved against him.

Later she went to get dressed, and Farrell began to tell Ben about Pierce/Harlow and the green convertible; but it kept getting scrambled, because Farrell had not really slept for thirty-six hours, and they had all suddenly caught up with him at once. Halfway up the stairs to the spare bedroom he remembered that he had wanted Ben to hear the two Luys Milan pieces he had just learned, but Ben said it could wait. “I’ve got a nine o’clock class and office hours. Sleep till I get back, then you can play all night for us.”

“Which one is the nine o’clock?” Farrell had curled up in his clothes and a quilt, listening to Ben’s voice with his eyes closed.

“My all-purpose monster. It’s an introduction to the Eddas, but I get in a little Old Norse etymology, a little Scandinavian folklore, a little history, related literature, and a key to the Scriptures. The Classic Comics version of Snorri Sturlesson.” His voice was unchanged—slow for New York, and light, but broken as erratically as an adolescent’s by a deep, random jag of harshness, strangely like interference on a long-distance call. When you hear somebody talking to Wyoming or Minnesota, just fo

r a moment.

Farrell fell asleep then—and woke promptly with Briseis washing his face. Ben turned quickly to call the dog away, and his words came out in a soft sidelong rush. “So what do you think of her?”

“Overdemonstrative,” Farrell grunted, “but very nice. I think she’s got worms.” He opened his eyes and grinned at Ben. “What can I tell you? Living with her has given you cheekbones. You never used to have cheekbones before, I never could figure out what was holding your face on. Will that do?”

“No,” Ben said. The kind, brown, dolphin gaze regarded Farrell almost without recognition, admitting to no shared subways, no Lewisohn Stadium all-Gershwin concerts, no silent old jokes and passwords. “Try again, Joe. That won’t do at all.”

Farrell said, “I was doing my old charming bit, and she pulled me up so short I think I ruptured my debonair. Remarkable woman. We may take a while.” His arm had begun to throb, and he blamed Sia for not leaving it alone. He said, “Also, I’m sorry, I can’t imagine you together. I just can’t, Ben.”

Ben’s expression did not change. Farrell noticed the scar under his left eye for the first time—dim and thin, but as ragged as if it had been made with the lid of a tin can. He said flatly, “Don’t worry about it. Nobody can.”

Downstairs the doorbell rang. Three-quarters asleep, Farrell felt Sia move to answer it, the heavy steps trudging in the bed. He mumbled, “Piss on you, Kassoy. Stand around like a junior high school girl full of secrets. I don’t know what you want me to say.”

Ben laughed shortly, which startled Farrell as much as anything that had happened so far that morning. When they were children, Ben had seemed most often to be straining on the edge of laughter, digging in his heels against the terror of finding everything funny. Farrell had seen the ghosts of murdered giggles burning along the perimeter of Ben’s body, like St. Elmo’s fire. “I don’t really know either. Get some sleep, we’ll talk later.” He patted Farrell’s foot through the quilt and started out of the room.

“Can you put me up for a bit?”

Ben turned back, leaning in the doorway. What is he listening for, what is it that has all his attention? “Since when do you ask?”

“Since it’s been seven years, and unemployed company with no plans is not a good thing. I’ll start looking for a job tomorrow, see about a place to live. Take me a few days.”

“It’ll take longer than that. You better bring all your stuff inside.”

“Jobs and parking spaces, remember?” Farrell said. “I always find something. Canneries, fry cook, hospital work, tend bar. Check out the zoo up in Barton Park. Fix motorcycles. Lay linoleum. Did I write you about that, how I got into the union? Ben, the people you let in your house to lay down your linoleum!”

Ben said, “I could probably get you a guitar class at the university in the fall. Not a master class or anything, but not Skip to My Lou either. It couldn’t be any worse than teaching out of the Happy Chicken Bodega on Avenue A.”

Farrell held out a hand to Briseis, who came and plopped her head in it and went to sleep herself. “I don’t even have a guitar anymore.”

“The Fernandez?” The Ben he remembered stared at him for just a moment, unprotected, always a little startled, and endlessly, maddeningly honest.

He said, “I traded it to the guy who made the lute for me. I had to be sure I was serious.”

“So you actually did something irrevocable.” Ben spoke softly, the fortress face expressionless again. Farrell heard Sia’s voice on the stairs, and under it a younger voice, muddy and sexless with pain.

“Suzy,” Ben said. “One of Sia’s clients, pays her by doing housework. Married to a surfing thug who thinks cancer’s contagious.”

“Is she really a psychiatrist, Sia?”

“Counselor. She has to call herself a counselor in this country.” The voices went into another room, and a door closed. Farrell asked, “Is that how you met? You never exactly said.”

Ben shrugged in the old lopsided way, ducking his head crookedly, like a fishing bird. He began to say something; but Sia was talking to the woman, and the slow, near-wordless pulse of her voice in the other room was beginning to wash Farrell gently back and forth, here and gone and here. With each lulling swing across the darkness, something he almost knew about her left him, the stone woman with the dog’s head last of all. Ben was saying, “So I thought you might as well be working at something you enjoyed.”

Farrell sat up and said with urgent clarity, “No, teeth. A purple in the back seat with teeth.” Then he blinked at Ben and asked abruptly, “What makes you think I enjoy teaching?” Ben did not answer. Farrell said, “I mean, I don’t not enjoy it. I dig anything I do well enough. All that stuff, those stupid little jobs, I just don’t want to start liking any of them more than enough. I like them stupid.”

Then Ben smiled suddenly and lingeringly, the comforting phosphorescence of suppressed delight flaring around him once more. Farrell said, “Now you’re thinking about my goddamn hat with the earflaps.”

“No, I’m thinking about your goddamn briefcase, and your goddamn incredible looseleaf notebook. And I’m thinking about how you could play, even then. I never did understand how that notebook could go with that music.”

“Didn’t you?” Farrell asked. “Funny.” He turned on his side, to Briseis’ considerable distress, and burrowed down in the quilt, resting his head on his arm. “Ah, lord, Ben, the music was the only thing that ever came naturally. Everything else I had to learn.”

Chapter 3

Nothing in Farrell’s considerable experience of frying eggs and hashbrowns had quite prepared him for Thumper’s. His work here was the opposite, the denial, the absolute negation of cooking: it consisted almost entirely of reheating dormant fruit pies, periodically adding water to the stewing vats of coffee, chili, and something orange, and filling red plastic baskets with sandy gobbets of fried rabbit, prepared in Fullerton in accordance with a secret recipe and delivered by truck twice a week. He also had the responsibility of steeping the chunks, either in Thumper’s Meadow Magic Sauce, which smelled like hot blacktop, or in Thumper’s Forest Flavoring, which Farrell had renamed “Twilight in the Everglades.” For the rest, he mopped the floors, scoured the ovens and the deep fryer, and, before he left in the evening, pulled the switch that lit up the grinning, eyerolling, foot-flapping bunny on the roof. The bunny was supposed to be holding a Big Bear Bucket of Cottontail Crispies, or it might have been Jackrabbit Joints or Hare Pieces. Farrell was entitled to one Big Bear Bucket a day, but he took his meals at a Japanese restaurant around the corner.

So did Mr. McIntire, the manager of Thumper’s. A hulking, silent man with a red face and hair as gray and sticky as old soap, he winced visibly to serve Wabbit Wieners and pushed the bright baskets of Bunny Buns across the counter with his fingertips. Farrell felt sorry for Mr. McIntire and made an omelette for him his fifth day on the job. It was a Basque piperade, with onions, two kinds of peppers, tomatoes, and ham. Farrell added a special blend of herbs and spices, acquired from a Bolivian lawyer in exchange for the lyrics of Ode to Billie Joe, and served the omelette to Mr. McIntire on a paper plate with pink and blue rabbit tracks printed all over it.

Mr. McIntire ate half of the omelette and abruptly put the plate aside, saying nothing, twitching his shoulders. But he tagged after Farrell all that afternoon, talking to him in a dry, mournful susurrus about mushroom and chicken-liver souffles. “I never meant to wind up running a place like this,” he confided. “I used to know how to cook burgundy beef, caramel baked beans. Bubble-and-squeak. Remind me, I’ll show you how to make bubble-and-squeak. It’s English. I used to go with this English girl, in Portsmouth, in the war. I was gonna open a restaurant in Portsmouth, but we broke up.”

“My famous mistake,” Farrell said to Ben and Sia that evening. “Stirring up the natives. He’s already talking about messing with the menu, trying to sneak some real cooking in among the Thumper Thighs before Disney sues the whole wret

ched outfit right into Bankruptcyland. No more omelettes for Mr. McIntire.”

He had been tuning the lute to play for them, and now he began on a Holborne galliard; but Sia’s silence made him fumble the first measures and stop. When he turned to look at her, she said, “But you might like that. To work for a man who is still discontent, who cannot quite resign himself to garbage. What’s better, if you have to work for someone?”

“Nope,” Farrell said. “Not me. When I’m a fry cook, I’m a fry cook, and when I’m a chef, that’s another thing altogether. I don’t mind giving, but I like to know exactly what I’m expected to give. Otherwise it gets confusing, and I have to think about it, and it troubles the music.”

Sia stood up with a movement so decisive that it wiped out all memory of her ever having been sitting. Her voice remained low and amused, but Farrell knew after a week that Sia only moved quickly when she was angry. “Cockteaser,” she said. She took herself out of the room then, and Farrell more than half expected to see the lamps, the rugs, and the stereo go bobbing after her, the piano spinning slowly in the backwash. The strings of his lute were all out of tune again.

Farrell sat with the lute in his lap, wondering if there could conceivably be a Greek word that sounded like the one he had heard. He was going to ask Ben; but then he looked across the room at shaking shoulders inadequately concealed behind an oversized art book and, instead, he retuned the lute once more and launched into Lachrimae Antiquae. His attack was a bit harsh in the opening bars, but after that it was all right. Sia’s living room was very good for pavanes.

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand Return

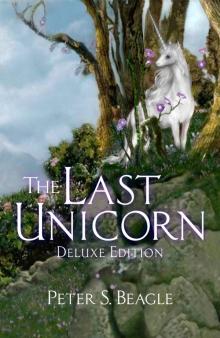

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

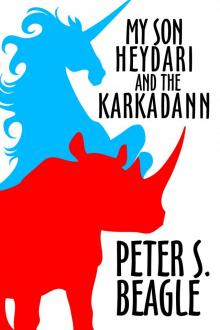

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

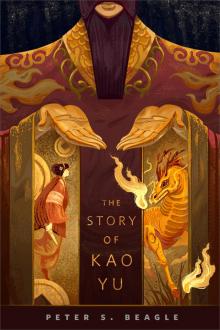

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

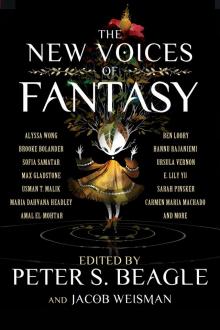

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

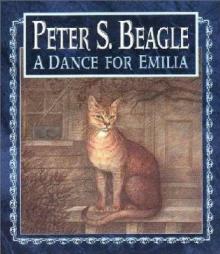

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song