- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

My Son and the Karkadann Page 3

My Son and the Karkadann Read online

Page 3

But poor Niloufar, flattening herself in vain against the elephant’s back, was knocked from her hold and hurled through the air. And the gods only know how badly she might have been hurt, if Heydari, my son, running as fast as though the karkadann were still behind him, had not managed to break her fall with his own body. She hit him broadside, just as Mojtaba had crashed into the karkadann, and they both went down together—both, I think, unconscious for at least a minute or two. Then they sat up in the high grass and looked at each other, and of course that was the real beginning. I know that, and I wasn’t even there.

Heydari said, “I thought I would never see you again. I kept hoping I would see your sheep grazing in the valley, but I never did.”

And Niloufar answered simply, “I have been here every day. I am a very good hider.”

“Do not hide from me again, please,” Heydari said, and Niloufar promised.

The karkadann was dead, but it took the children some time to call Mojtaba away from trampling the body. The elephant was trembling and whimpering—they are very emotional, comes with the sensitivity—and did not calm down until Heydari led him to the little hill stream and carefully washed the blood from his tusks. Then he went back and buried the karkadann near the cave. Niloufar helped, but it took a very long time, and Heydari insisted on marking the grave. As well as that girl understands him, I don’t think she knows to this day why he wanted to do that.

But I do. It was what he was trying to tell me, and what I hit him for, and likely still would, my duty as a father having nothing to do with understanding. The karkadann was magnificent, as he said, and utterly monstrous too, and he probably came as near to taming it as anyone ever has or ever will. And perhaps that was why it hated him so, in the end, because he had tempted it to violate its entire nature, and almost won. Or maybe not . . . talk to my idiot son, and you start thinking about things like that. You’ll see—I’ll seat you next to him at dinner.

No, we’ve never called them anything but karkadanns. Odd, a Roman fellow, a trader, he asked the same question a while back. Only other time I ever heard that word, unicorn.

About the Author

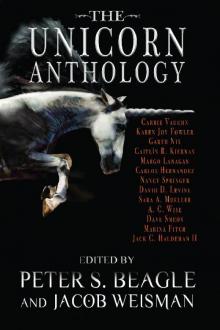

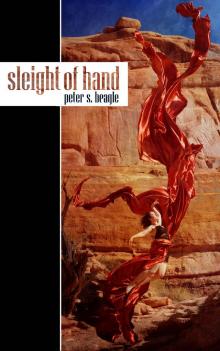

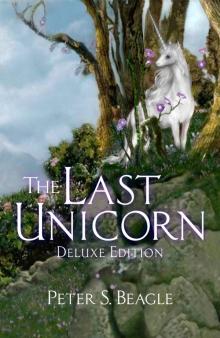

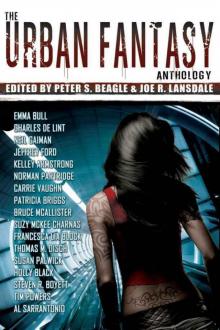

Peter Soyer Beagle is the internationally bestselling and much-beloved author of numerous classic fantasy novels and collections, including The Last Unicorn, Tamsin, The Line Between, Sleight of Hand, Summerlong, and In Calabria. He is the editor of The Secret History of Fantasy and the co-editor of The Urban Fantasy Anthology.

Born in Manhattan and raised in the Bronx, Beagle began to receive attention for his artistic ability even before he received a scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh. Exceeding his early promise, he published his first novel, A Fine & Private Place, at nineteen, while still completing his degree in creative writing. Beagle’s follow-up, The Last Unicorn, is widely considered one of the great works of fantasy. It has been made into a feature-length animated film, a stage play, and a graphic novel. Beagle went on to publish an extensive body of acclaimed works of fiction and nonfiction. He has written widely for both stage and screen, including the screenplay adaptations for The Last Unicorn and the animated film of The Lord of the Rings and the well-known “Sarek” episode of Star Trek.

As one of the fantasy genre’s most-lauded authors, Beagle is the recipient of the Hugo, Nebula, Mythopoeic, and Locus awards, as well as the Grand Prix de l’Imaginaire. He has also been honored with the World Fantasy Life Achievement Award and the Inkpot Award from Comic-Con, given for major contributions to fantasy and science fiction.

Beagle lives in Richmond, California, where he is working on too many projects to even begin to name.

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

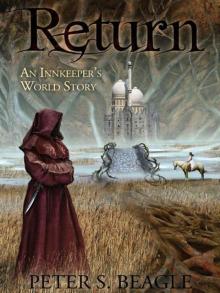

Sleight of Hand Return

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

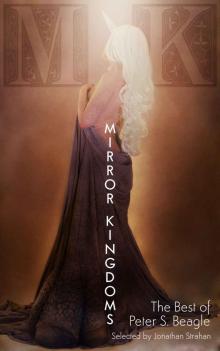

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

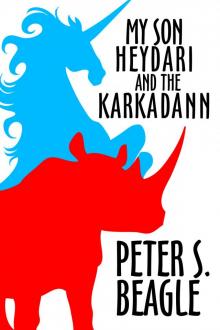

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

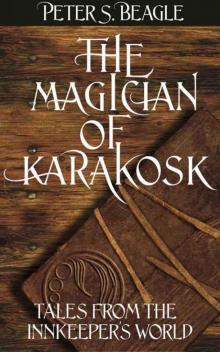

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song