- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

In Calabria Page 4

In Calabria Read online

Page 4

Speechless for a second time in a matter of minutes, Bianchi finally managed to grunt, “Welcome.” Giovanna said nothing further, and they walked in silence to the blue mail van. As she stepped into the cab, she reminded him, “I will call tonight. Just to ask about her.”

Bianchi nodded. He handed the three envelopes back to her, raising his eyebrows slightly. Giovanna said, “I will throw them away for you.”

Watching the van careen away down the steep road, he surprised and irritated himself by calling after her, “Be careful!” The child does not have a license, I am sure of it. Who would give such a little girl a driver’s license? Yet he stood where he was for a time, until he heard the cows calling to be brought into the barn and milked. I hope Romano has warned her about the curve near old Frascati’s farm. It can be dangerous going downhill, and she drives too fast.

Giovanna did telephone him that night, as she had said she would do. He told her shortly that there was nothing to tell her: the unicorn had not gone into labor, or anything like it, but had grazed periodically—most often in the company of Cherubino and one or two of the cats—and seemingly dozed in the hollow at times, but never for long. “I am not sure that she ever sleeps, not truly. It is all very strange, her being here. Writing the poems does not make it any less strange.”

“Romano has found a book at the library. There is a lot about unicorns in it. I will read it tonight. I am to drive the mail van on Fridays, so I will see you then.”

“I will look for you,” Bianchi said, but she had already hung up.

In the weeks that followed, the unicorn’s pregnancy became more evident—even someone who was not a farmer, like Romano, would have noticed the change—but her behavior altered not at all. She did spend more time resting in the hollow, nearly invisible in the shadow of the earthen overhang, but still capable of being up and gone in a soundless swirl of cloven hooves. Bianchi would watch her for long minutes and hours, immobile himself, and sometimes ask her aloud, “What can you be thinking? What do you remember, so graceful, so serene, gazing so far away, so far beyond my tired fields? What dreams come to you as you lie there open-eyed?” for she never closed them entirely while he was near. “Do you dream about the one who is coming—do you wonder about . . .” and he would invariably stop at that point, even in the poems. Even the poems never pursued that last question.

That urgency was left to Giovanna, who asked it early, and with increasing intensity as the days passed. “Where is the father, do you suppose? Where can he be, her mate?”

She was sitting on the ground close to the unicorn, closer than Bianchi himself was ever permitted, which always annoyed him. “Why do you ask me? What should I know about fathers?”

“Bianchi, a unicorn is not a cat, to go around mounting every female in season—if unicorns have seasons, the book is not clear. I am sure that her mate, her stallion, whatever you want to call him, knows, knows, that this child is to be born, and he is looking everywhere for her, to be there when it comes.” She had rarely spoken this much in any one burst, and she literally ran out of breath and suffered a small coughing fit. Bianchi patted her back gingerly until it stopped.

“No book will tell us what we want to know, Romano’s sister,” he told her. “It was only a little while ago that I could not imagine that there could be such a wonder in the world as what we look on together in this moment, you and I. Perhaps her mate will come for her and the child, and perhaps not—it will all be according to the ways of unicorns.”

He paused, uncomfortably aware of Giovanna’s green, listening eyes. There was a small heart-shaped birthmark at the corner of the left one. “But this much I do know. This I will tell you. Seeing her even one time would have changed the poetry forever, just as it happened to Dante, who saw Beatrice only once, at a May Day party when she was eight years old. I have seen her every day now for months—a magic, an enchantment, walking around my farm, eating weeds with my goat—and it has made me different. I cannot even say how different, different in what ways—only that I am.” He blinked rapidly, though Giovanna saw no tears in his eyes. He said, “When she is gone, then perhaps I will know.”

When Romano asked whether she had detected any signs of a woman appearing in Claudio Bianchi’s life, Giovanna would shrug with practiced disdain. “I am never in his house, what can I tell you? I do what you do—I drop off the mail and I go, punto e basta. As far as I can tell, he lives alone, as he has always done.” Sometimes, merely for the pleasure of teasing her brother, she might add, “Of course, he might have a friend who comes to visit now and again. That does happen, you know.”

Romano disapproved of the possibility. “He is an old man. He needs someone there, someone who will take care of him.”

Giovanna would most often shrug again. “Perhaps so. Me, I ask him no questions. Go away, I have studying to do.” Once or twice, to plague him further, she remarked lightly, “He is not quite as old as all that, you know.”

Spring comes earlier in Calabria than to anywhere else in Italy. The sunrise howling of the tramontane winds gradually decreases, and is most often followed by the warm, wet southwesterly flow of the sirocco that can bring flowers out of the ground before the weather is quite ready for them. Bianchi himself often felt a childlike desire to run around warning the new poppies and blossoming bergamot trees, “Not yet, not so soon, it is a trick! The cold rains will return and beat you back into the earth—stay down, stay down a while longer!” But this year there seemed no danger of such a betrayal: the days warmed steadily, the soft young grass was welcomed eagerly by cows grown weary of stale hay, the three cats roamed more widely, and even Garibaldi stayed outside on some nights without whining to be let in. Bianchi saw black storks going over, and heard the cries of northbound geese in the night.

The unicorn grew heavier and somewhat slower afoot, eating little, but drowsing often in the returning sun. The life within her was visibly more active, most often in the afternoon, and Giovanna made a point of timing her Friday mail deliveries accordingly. She never offered to take Romano’s route more than one day a week. “Because he will become suspicious, immediately. He is not nearly as stupid as he acts.”

Bianchi looked puzzled. Giovanna felt oddly embarrassed, and annoyed with herself for feeling so. “He will think I have a lover.”

“Oh,” Bianchi said. “Well, you don’t.” After a moment he added, “Do you?”

Giovanna raised one black eyebrow before she answered. “No fear. They are all too much like Romano around here, nervous if you roam too far away from the stove and the bed. I certainly hope his Tessa can cook for him when I graduate and run off with his mail van.”

Bianchi said nothing, not always being entirely certain when Giovanna was joking. They were standing together, watching the unicorn grazing alone in his vineyard, where he had first seen her. Neither spoke for some while—Giovanna was proving an almost distressingly comfortable person to be silent with—until she finally said, “It will be soon. The new one wants to be born.” She never referred to the coming infant in any other way.

“It will happen in the middle of the night,” Bianchi grumbled. “It always happens so with the pigs, always.”

“Bianchi, a unicorn is not a pig, any more than she is a cat. It will happen, I think, when she decides that it is time.” After a long, thoughtful moment, she added, “Perhaps it has to be born on your farm, for some reason we will never know. Chi lo sa? Perhaps she came from some other century, all the way across the ages, just so her child could take its first breath right here.”

She tugged at her hair, something she did only in moments of anxiety. “What troubles me is that I will not be here for the birth. Unless it is on a Friday.”

Bianchi was silent for a long time before he surprised himself by blurting out, “Then I hope it does happen on a Friday.” Giovanna turned her head to look at him. He said, “I would feel . . . better if you were here.”

After some while, Giovanna said, “Yes.” br />

They went on staring straight ahead, watching the unicorn nibbling on fallen grape leaves. Bianchi said presently, “I call her La Signora sometimes. Not for her to answer to, but just for me, inside.” Giovanna nodded without answering.

The birth did not come on a Friday, but on a Thursday, and it came on such a night of wind and rain as had not been seen for a month. The sirocco has no specific season, but blows as and where it chooses, at times almost as fiercely as the tramontane. Yet it was not the wind that awakened Bianchi, but Cherubino on his hind legs, butting at the bedroom’s single window with nose and horns. One look at the goat’s demonic, desperate face, and Bianchi was out of the house, barefoot, a raincoat thrown over his old-fashioned flannel nightshirt, stumbling toward the hollow where the unicorn lay on her side. Her eyes were open and clear, and she was breathing calmly, but Cherubino knew, and so did Bianchi. Without thinking, he crouched beside her—far closer than he had ever dared approach—and put his hand on her neck where it joined her body. He felt the immortal heartbeat against his palm, and for a moment he shut his eyes. He moved his hand to her belly and listened.

“The child is coming the wrong way, Signora,” he said, raising his voice against the wind. “I know what to do, but you will have to trust that I know.” The unicorn lay still under his hands. “Well, then. So.” Salt, soft against my eyes . . . the Doctor’s Wind, blowing home from the sea—that must surely be a good sign, surely . . .

The rain began as he was trying to find a courteous manner to keep the unicorn’s tail out of the way. She lay half-sheltered by the overhang of the hollow, with most of her body exposed to the increasing downpour. Bianchi grunted with distant annoyance, pulling off the ancient raincoat to throw over her. He held up his hands to the pounding rain—at least they would be as clean as possible—and went on talking to the unicorn, telling her and himself, “It will go well, we will go well, do not be afraid . . .” I must not let her be afraid—her or the little one. “It will go well, Signora—my beauty, my sweetheart . . .”

It did not go well, not in the beginning. The colt—as he had finally determined to think of it—was almost impossible to turn, and Bianchi could feel its terror all along his arm, no matter how comfortingly he spoke to it. Throwing all his strength into the effort, if I can get hold of that foreleg, the one folded up so tightly, but what if it breaks? he pushed blindly but what if it breaks? what if the little one is strangling in the cord right now just the way don’t think about it the same way don’t ever think about it . . . Then suddenly the small body began to come almost too easily, so that he was first alarmed at the possibility of the sharp tiny hooves hurting the mother—though La Signora remained as placid as he could have wished—and then of the colt having died before it had ever lived. O God, God, what will I do then, what will I say? Yet he kept sensing its living fear in his own body, that has to be a good sign, and tried to imagine what it would be like to see Giovanna running to the hollow in the morning.

Then a surge—a rush of watery blood—and the little head was free: damp, wild-eyed, gasping its first breath in the rain. The unicorn raised her own head, twisting her neck for a first sight of the newborn, but Bianchi said sharply, “Aspetta, Signora—wait, wait, lie still!” To his amazement—not then, but afterward—the unicorn obeyed, as he bit the cord in the oldest of ways, and slowly guided her child, slick and wriggly as a tadpole, into the screaming world, trying to shield it from the storm with his body. The horn is just a tiny bud, of course, it would hurt her otherwise. In a vague way, he noticed that the newborn’s coat shone as black, even through the rain, as its mother’s shone white. Like her hair . . .

When he brought the baby’s mouth to a distended nipple, the unicorn made the river-sound that he had heard before, so softly that he barely heard it under the wind. Soaked and frozen himself, strengthless, he huddled as close to her as her child did, and it seemed to him then that she provided sheltering warmth for the three of them. It seemed also that he heard, in his exhausted sleep, the weeping of the black-haired woman like broken glass in my heart her tears, and he buried his face against the unicorn’s belly until he could not hear the weeping anymore.

That was how Giovanna found them when she managed at last to coax and command the blue van up the hill road, spongy with rain and doubly treacherous even with the storm blown over and the sun shining. The black newborn was already trying to stand on shaky legs too long to manage, but the unicorn lay as patiently still as ever while Bianchi slept like the dead across her body. Indeed, Giovanna thought, for one heart-numbing moment, that he really might be dead, so motionless he lay. She had to kneel close before she heard him snoring gently; if she thanked God, she was quiet about it. One moment to disbelieve the wonder of a unicorn’s breath in her palm; then she was hauling Bianchi to his bare, muddy feet, tugging his arm across her shoulder, coaxing him. “Vieni . . . vieni, amico . . . come on, come on, my friend. Time to go home . . .”

Lurching the first few steps with him, she almost stumbled into what she took at first for a shallow depression, and then realized as a hoofprint, cloven as precisely as La Signora’s, but distinctly deeper and broader than those. When she turned her head, she could see them circling the hollow until they vanished—whether among a stand of olive trees or into the bright new sky, she could not tell, and there was no time to study them further.

Somehow she half-dragged Bianchi all the way back to his house, pulled his nightshirt off over his head, rubbed him dry unashamedly—Romano was not her only brother—then wrestled him into his bed, and poured coffee, liberally infused with grappa, into him until he coughed and waved it away. With his eyes closed, he said, “It was turned around . . . the little one . . . it did not know the way.” His voice was hoarse and slow. “I tried so hard . . . I am sorry . . .”

Giovanna stared at him. Bianchi put his hands over his face. He whispered a name that she did not catch. “I am sorry . . . I am so sorry . . .”

“Bianchi, they are both well,” Giovanna said. “The little one is almost standing. Do you hear me, Bianchi?” He did not answer her. She said, “Sleep. She can take care of it now.”

At the door, without turning, she said, “I was afraid for you.” She left without hearing Bianchi’s reply, which he missed himself, being asleep at the time.

“. . . wished you there.”

He slept late into the afternoon. On waking, he dressed himself, drank a great deal of water, and foraged absently in the refrigerator for a few remains of last evening’s dinner. He let the cows out, and then walked slowly to the hollow, accompanied by Cherubino and all three of the cats. The unicorns—mother and son, white and black—appeared to be waiting for him there, the colt notably firmer on its legs than he would have expected, La Signora as calmly elegant as though Bianchi had never had an entire hairy arm inside her, groping blindly in her darkness for her child.

For a moment she put her head lightly on Bianchi’s shoulder, and, as he had never done, he touched the horn. It felt smooth and harsh to his fingers at the same time: there were hard, slightly raised rings at regular intervals under the sleek spiral surface, ascending to the tip, as far as he could judge, having no mind to chance the gleaming tip. La Signora is a dangerous animal. La Signora is very dangerous.

“You must be careful,” he said to her. “You did well to choose this place when you knew he was coming, because so few people ever visit me, and your folk know everything about living unseen. But he changes things.” Bianchi could not tell whether or not the colt understood him as La Signora did, but the little one was watching him just as intently, out of the same deeply dark eyes. Simply by the way in which he braced his new legs, standing beside his mother, Bianchi would have known him for a male of any species.

“He changes things. You will not be able to travel until he can keep up with you, and meanwhile you are more visible together, even here. Children are—” he hesitated painfully, what can I know about children? I only know kittens, calves, po

ems—“children are curious, Signora, children want to go and see. You must make him understand . . .”

Here he stopped, this time for good, because the ludicrousness of admonishing an immortal creature to be careful was a little more than his sense of the absurd could tolerate. He reached out a hand to the colt, which promptly skittered away from him, as though they had not been intimately involved mere hours before; the gesture ended awkwardly on the cheek of La Signora. She regarded him out of a dark kindness that made his eyes ache, and he was the one who stepped back and lowered his gaze. “I will keep you safe. You and him.”

He had not been back in the house for ten minutes before Giovanna called him. She was crying.

“Forgive me . . . I didn’t mean . . .” It took Bianchi a few moments to recognize the nearly hysterical voice as hers, and longer to comprehend what she was telling him. “I didn’t mean to . . . but seeing her, seeing her and the little one, I came home on wings, on wings, and Romano . . . Romano took one look at me and he saw, and he asked, and he kept on, he kept asking . . . and I was, I was so happy, and so . . . forgive me, Claudio . . .”

He was too bewildered, and increasingly alarmed, to take in the fact that she had called him by his name for the first time. “I didn’t mean, it was just . . . I was so happy . . .”

“What?” he demanded. “Stop crying! What are you saying?” But he already knew.

“I told him!” Giovanna wailed. “It just came out—your Signora and her baby . . . everything, everything. And he will be driving up to see them the first thing tomorrow, even though it is not a mail day. I feel like dying—I am so ashamed . . .”

“Basta! Stop that bawling, woman!” He shouted it the second time, as harshly as he could, and was rewarded with startled silence, punctuated by sniffles. More quietly, he said, “It is my fault as much as yours. More—if I had been paying attention the first time you came, you would never have seen her, never known. Stop blubbering now, you are not someone who blubbers.” This provoked a startled, slightly hysterical giggle, equally as disquieting to Bianchi as her tears. “Listen to me. What happens now will be by her choice—in the end everything is by her choice, always has been. If she does not want Romano to see her—see them—then he will not see her, that is all there is to it. Wash your face and have your dinner, and go to bed. Buona notte.”

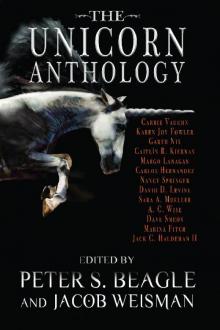

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

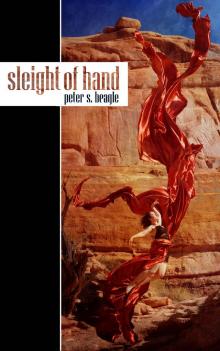

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

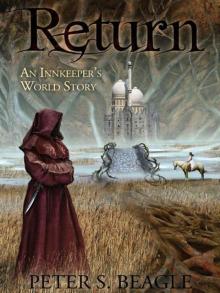

Sleight of Hand Return

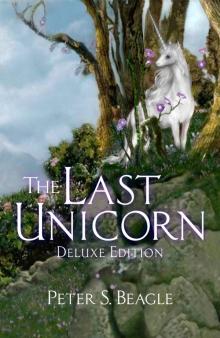

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

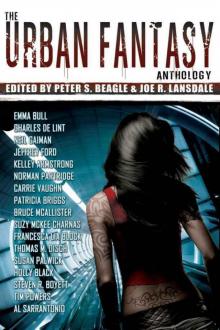

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

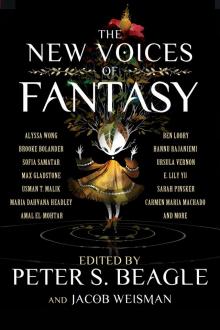

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song