- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

Return Page 4

Return Read online

Page 4

I have, from time to time since, seriously considered taking another name, to be rid of the sound of his voice speaking this one. His smile widened, but the blue eyes…no, there is no comparison for those eyes, no declaring that those eyes were like anything else. They were just what they were, and I see them still. He spoke softly, with that upward, questioning lilt they all have, always. He said, “Fool?”

I shook my head—not to deny his judgment, the gods know—but to clear it as best I could, and to focus on that face I had last seen when I was shoveling earth on it with my hands and my unstrung bow. He repeated, “Foolish Soukyan? Foolish.” And his smile gobbled me up—I could truly feel myself sliding down his throat: whole, headfirst. The Hunter said, “Tricked. All the way.”

“Yes,” I said slowly. “Yes, I see that now. Not a mark on you beyond that forearm scratch, and still I took you for dead. I knew you were dead. No breath, no heartbeat.” I shook my head again. Obviously he did not need these things in the normal fashion or degree. I said, “Fool, yes. You tricked me into coming here. From the beginning.”

“From the beginning.” The Hunter laughed fully then, and actually slapped his thigh. I had never seen such a thing before. He said again, “All the way. Never a moment out of Masters’ sight. Not riding, not sleeping—not even when you…when the woman-face came.” Hunters are strangely prudish about women: that was the best even he could manage in reference to the guise he was now telling me had made no difference. “Deceived nobody. Not Brother Laska, not Master Caldrea, nobody. Welcome home, Soukyan. Good to see Soukyan. Never leave us again, Soukyan. Never leave again.”

He sat down beside me, and said, softly, “All my brothers? So many, I can only kill you once? Unjust.” He did seem a bit depressed as he set to his work.

We think of torture as a matter of instruments: racks, heated irons, pincers, crushers, knives, razor-edged flails. The Hunters, however, take great pride in their skill, and this one produced only a small silver knife very similar to the one with which Master Caldrea had peeled the sulyak pear during our dinner. It may well have been the same knife, for all I know—I recall that the tip was daintily divided for a little way along the blade, and I certainly remember for what purpose. It is not quite so efficient on flesh; after awhile he tossed it aside with an irritable grunt. I hear that sound in the middle of the most pleasant dreams, often, even now.

After that he went at me like an insane masseur, like a butcher tenderizing a tough slab of meat—no, better, say rather a fisherman working over the giant shellfish that South Island folk call shamokin, but coast people name marlouk. The belief common to both is that the creature must die in a state of relaxation, or it will become almost unchewable in minutes, no matter how long you pound it. I braced myself in every way I knew against the ceaseless, merciless storm of hand-edge hammer-blows to my gut and groin and face (blood there, a good deal of it, spoiling his record); to my neck and throat as well; to every vulnerable ligament, muscle and tendon in my body, and even to my hair, which he would grab to haul me back to pain each time I lost consciousness. Looking up into his blue eyes as he slapped my head back and forth, grabbing my jaw, my whole mouth, between his thumb and fingers, I could feel through my bones how badly he wanted to kill me, and I would grin my red grin in his face, because I knew it would not be allowed. Then he would hit me harder, because he knew it too, and I would go away again, and so it went, world without end.

But there are a few ways of dealing with even the worst agony—of absenting oneself from it—that the man who laughs taught me long ago, and I employed them to their fullest extent, as I had prepared myself to do the instant I looked into the third Hunter’s mad blue eyes. For three different purposes were crowded into my cell that day, and I kept reminding myself that I needed to stay present, so I could pay attention to all of them. This is difficult when you keep being beaten to the brink of death by someone who knows how to do it, and has every intention of doing it once for each of his cohorts you have killed. I know this, because the Hunter told me so. Each time.

The Masters themselves obviously wanted something from me, some information that I must eventually yield up to them to stop the beating. And I would yield it to them in time, but not until I focused more clearly on exactly what they were saying to one another as they watched the Hunter taking out his fury on me. Because I wanted something too. If I had been lured back to that place by a false death and other possible deceptions, that did not mean that there was no greater truth to be found. If I could only hold onto consciousness long enough—the periods of coherent awareness were definitely becoming shorter—and if the Hunter could only be kept from going over the brink himself and taking me with him, what I was enduring might yet turn out to be worthwhile.

Finally he hit me hard enough that I actually skidded across the cell floor on my back, coming to rest with my head almost between one Master’s foot and what I recognized as Master Caldrea’s fine sheknath-leather sandals. I felt his voice in the stone under me, rather than hearing it. “That will be enough for now. Enough! When he comes to himself, I will question him.”

I kept my eyes tightly closed, feeling the Hunter’s breath on my face. But he did not touch me. I heard the other Master say pettishly, “I would like it to be recorded that I have found this entire affair distasteful in the extreme. If the man had anything of value to tell us, he would surely have babbled it all at least an hour ago.”

“So noted,” murmured Master Caldrea. “But you do not know him as I do. He is Soukyan, and he has killed more Hunters than you, Jedrath, have had your wine glass refilled. It would be more than worth our time to learn how he became our nemesis, even if we had nothing more than that to concern us. Even if the Tree were not dying.”

It took more will than surviving the Hunter’s best efforts not to pop my eyes open and demand details. There was a Tree then, and it was somehow intimately connected with the existence of the Hunters, the Masters, and that place itself. I knew that this, finally, was the reason I had been lured back here—though I could not yet see the purpose.

The Master named Jedrath asked, somewhat hesitantly, “That is certain, then? There is no saving the Tree?”

“There is now,” Master Caldrea said.

The Hunter growled, “He wakes.” I gave up pretense and opened my eyes just as he reached for me. Master Caldrea made a small sound, and the Hunter confined himself to dragging me abruptly into a more or less seated position. The cell spun in and out for a few moments, and I would have vomited, but I had already done that two or three times. The Masters quite kindly waited for me to find my equilibrium before questioning me. Master Jedrath even tossed me a rag to wipe away the blood from my nose and mouth.

I spoke first, thinking to take them all perhaps a little off-balance. I said thickly, “I presume you have questions for me. Ask them, and I will answer if I can.” I peered at them through fast-closing eyes. “Or was all this activity merely for my amusement?”

Master Caldrea said, “Hardly that. We have been speculating for years—almost since you left us, really—on just how you acquired the skills that let you evade and kill our Hunters, time on time.” He shrugged, slowly and gracefully. “We felt it necessary to inquire directly.”

I suddenly felt very tired, and not entirely from the Hunter’s work. I said, “No. That makes no sense at all. All this effort to bring me here, tricking me into believing that it was my own will…all for some absurd course in combat strategy? Even with my mind still bouncing between the walls of my skull, I would know better than to believe a single breath of that. Please, ask what questions you will, but make them real ones. I should like to take a nap before dinner.” The blood from my nose had stopped flowing, but I knew it was broken. It has happened before, and since.

Jedrath whispered loudly to Master Caldrea, “Ask him what he knows of the Tree.”

Master Caldrea gave him a cold, disgusted look. Possessed on the instant of a small and ridiculous demon, I

croaked, “The Tree, yes…I have come to destroy the Tree. I will cut it down and tear up the roots, so no one will ever know where it grew.” I said that last part two or three times, because I liked the way it sounded. I don’t think I was yet quite back in my right mind.

“He knows nothing,” Master Caldrea said. Exactly as courteously as though he were bowing himself out of my rooms after another pleasant dinner, he said, “I’m sure we will be speaking again in the near future.”

“I look forward to it,” I said. I believe I even bowed where I sat, as much as my ribs would let me.

The Hunter stayed briefly after they had gone. He put his face so close to mine that I could smell the odd faint oiliness of his laughter, warm in my ear. He whispered—no question-cadence in his voice now—“Nothing you do harm the Tree, never. No axe you swing ever touch the Tree, no spade of you ever dig into, no poison you put to the Tree ever bite—no fire, no fire you set…”

And he stopped. Just for a moment, no more, before patting my cheek, almost caressing it with a certain awful tenderness. He stood up and said, “We wait for you at the Tree soon,” and I looked again into those blue eyes, and I nodded. With that he left, and I crawled into one corner of the cell, where I ambled in and out of sentience for the next several hours.

I was left alone for the next several days, during which I mainly slept. I ate so little, in fact, that Master Caldrea clearly came to fear that I might be a little too damaged to recover, or had spitefully determined to fast, to starve myself to death. I had no such plan, but I did enjoy watching him worry—he was an anxious man, under the coolly knowledgeable exterior—and I especially savored his one diffident apology. “I assure you, I took no pleasure in what was being done. It was not something I would have chosen to do, of my own will. But the Hunters…the Hunters are born obsessed with you, and had I forbidden it.…” A single graceful shrug, a quick gesture of both open hands, and that was the end of it.

Still, he came every day, until he was satisfied that I was fully recovered from my ordeal. And he brought me plain new garments, to replace the bloodied, soiled tatters I was wearing. I hesitate to say that he felt any least guilt or shame—such emotions are completely foreign in that place—but I suppose it could have been so. I will never know now. What I did know, lying there, was pitifully little: that there was indeed a Tree, that it was irremediably close to death before I came, and that my blue-eyed torturer fully expected to meet me again there soon. As for what purpose, I felt reasonably certain that it could not be something enjoyable. Not for me, anyway.

“The moon is the moon.” I came back to that more often than I revisited anything else that Master Caldrea had told me. In my experience—and even then, I had more of it than I liked—anything involving the moon usually takes place at its fullest, or when it stands at zero, vanished altogether for two or three days. Immured in this windowless cell, I had no way of knowing the phases of the moon, or day from night. But when I felt strong enough I knew in all my battered bones that it was time for me to go. Now. That moment. Literally.

And I knew a way to do it, a way that I had always known. A way that I had never wanted to take, and never had, and did not want to take now. But there was no choice.

The man who laughs taught it to me. Separately he had taken both of us in, Lal and me, many years before we finally met, and he taught us each exactly what we needed to know, even though neither of us could have imagined it at the time. In Lal’s case he gave her an emerald ring to ease the nightmares born of a slave’s childhood, and a little gardener’s charm as well, one that would raise the dead as easily as a cabbage. He also introduced her to the deep sea, which claimed her heart the moment she set foot on a battered, pitching old fishing boat. She will die there, at sea, like enough, though not while I can prevent it. Even as much as I hate boats.

For myself, he gave me the woman-shape, which made absolutely no sense to me at the time, but which had more than once preserved the strange life he knew was marked out for me. There was another gift too—one that came at a cost. They all do, really, but most often you don’t know it until the gift has been employed and the price is at your door. With this one I knew the price well in advance.

At first I was not even sure I recalled its workings. I did know that it involved certain incantations and certain…other spells, if you will, which would have been difficult to conceal in the limited privacy of my previous cell. Here, alone in the dark, I managed surprisingly well, saying the right words at the right moment and feeling my way through the few other things you have to do, just as the man who laughs had shown me, over and over, so very long ago. I was quite proud of myself, and liked to think that he would have been, too.

But how do you tell, in utter darkness, whether or not you have become invisible?

You go on bumping into things, of course, and you can’t see your hand before your face any more than you ever could. I had no idea whether or not the charm had succeeded until I stepped out of my unlocked door and approached the guard, who was still yawning in my face and scratching his belly when I laid him gently down to sleep. It is quite a tidy and efficient spell, really.

It also endures no more then a quarter of an hour; seventeen minutes at the outside. Seventeen minutes, paid for with at least three years off your life span, or as many, possibly, as five. But years there will be, and I could only hope that I was sacrificing time during which I’d just as soon have been dead anyway. The man who laughs told me that he himself had used it more than once; but then, of course, he was a wizard. Wizards live a very long time.

The moon was only a pale gray fingernail above me as I limped through the great doors. It seemed to be flickering feebly, like a candle about to fail. There was no turmoil, no noise of discovery and pursuit; none of my poor guards must have wakened yet. But they would, so I made off toward the marshes, exactly as I had done before, determined to be well away before the spell wore off or any alarm was raised. Being no longer the young man who plunged blindly and wildly down a weed-slick slope—cracking his head open on a rock, almost ending his flight right there—I circled cautiously, watching where I put my feet, and went to ground no more than half a mile from that place. By then I was solidly visible again. Finding dry leaves under a shroud of damp ones, as the fox had taught me, I put moons and Hunters out of my mind, and caught what sleep I could.

If they had had dogs…but of course they never did, completely reliant on the Hunters as they were. I woke to voices carried on the wind, too distant to be intelligible, and with no indication that they were drawing closer. I washed and drank at the nearest stream, numbed my hunger with tilgit, which grows wild throughout the marshes; and examined the sky, satisfying myself that the following night would show no moon at all. That would be my night. The Hunters might or might not be waiting for me, but I was coming for the Hunters. And the Tree.

Madness? Bravado? Both, and neither…and all that I had become since that first Hunter made a professional killer out of me. Yes, it was a killing that sent me flying to the shelter of that place as a child, the murder of the man who had so injured my sister—but it was killing the Hunter, seeing those contemptuous eyes widening with the shocked understanding that his pitiful, helpless victim, armed with nothing but the broken haft of a paring knife, had struck him down, had ended him, that truly changed me…it is not a good thing to feel that powerful. It is not. I would unlearn it, if I could.

Between now and tomorrow’s absent moon, I had plans to make and a day to use wisely. The morning was annoyingly bright and clear, but I moved with the sun, taking advantage of every shadow and every fragment of shade as I eased closer to that place. I could make out figures and faces coming and going; compared to its normal somnolent air, the mansion was humming like a nest of those little black miriki bees that do not die when they sting you. I recognized two or three guards, and even the boy who had told me how dishes were returned to the kitchen. But I saw no sign of Master Caldrea, which concerned me a goo

d deal.

Indeed, it concerned me enough that I risked recapture more than once, hoping even to spy him through a window. I knew better than to assume that he had given up on my recapture, nor to imagine that he imagined that I could choose escape over revenge. I slipped back into cool shadow on my belly, and thought hard about Hunters.

Once you have observed Hunters at close range—and presumably survived the encounter—you can never mistake them again. But I had spied none since my arrival, except for the one who had tortured me, and surely they would have been alerted since my escape. As a boy, I had seen them on rare occasions: small to medium in height, lithely built, with light eyes, pale brown skin, and distinctively quick, agile movements. They had nothing I could ever discover to do with the actual workings of that place: we youngest servants generally thought they were a special kind of monk, while the older boys hinted darkly at their real function, and dared us to approach and speak to one. I certainly never did, and I never knew anyone who took up the challenge. The Hunters look like what they are.

But I had seen none during the time I was held captive in the guest wing—nor during any of my escape attempts, either, when one might think Hunters would have been much in evidence. I spent much of that last day roaming the entire area, always returning to that place, chancy as it was, wondering where they were and still hoping for a sight of Master Caldrea.

I finally got my wish late in the afternoon, when he came briskly through the double door, walked into the open, then halted midway to the bushes and to shout this speech to the air. “My dear Soukyan, if you are within the sound of my voice, as I would think you are, may I first heartily praise your determination and your ingenuity—and may I also assure you that these admirable qualities will make no least difference to the outcome of this night. Savor your remaining hours here, since I do not for a moment imagine you will be wise enough to employ them in running for your life. Which would not help, either; if I wished to call them off now, they would pay no slightest heed to me. Take it as a compliment, Soukyan, and do enjoy this beautiful evening. The night will be less so.”

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand Return

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

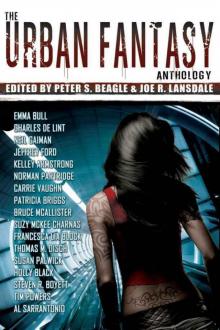

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song