- Home

- Peter S. Beagle

The Folk Of The Air Page 6

The Folk Of The Air Read online

Page 6

“Does this bus go to Inverness?” he asked. “I need a glass of water.” Julie hit the brakes again, for no apparent reason, and Farrell’s nose smacked hard against the back of her helmet.

She said, “This bus is off-duty, the driver carries only five dollars in change, and the first free moment I get I’m going to pound you into an omelette, Farrell. Jesus Christ, you don’t just do that to someone, who the hell do you think you are?”

“Your old college sweetie,” he answered meekly. “Who hasn’t even known where you were for three years.” Julie snorted, but the motorcycle accelerated a bit more smoothly, slipping past a low-rider convertible which was blocking traffic like a mauve kidney stone. Farrell said, “Who was so glad to see you that he got a little, as you might say, transported.” He paused, and then added, “As someone was pretty damn transported to see him one time. In Lima, was it?”

Julie made a sharp and very sudden right turn, canting the BSA almost onto its side, like a racer, and gunning it uphill for two blocks as Farrell shut his eyes and clutched her. Handling the great machine as deftly as a feather duster, she whisked it to the curb in front of a fraternity house and cut the engine, pulling off her helmet as she turned toward him. “In Lima,” she said quietly. “In the market.” Farrell dismounted to let her haul the BSA up on its stand, and they stood the bike’s length apart, wary and uncomfortable, staring at each other. He saw that she had let her black hair grow below her shoulders again, the way she wore it in college.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I was just grateful, you don’t know.” Julie studied him a moment longer; then blinked, shrugged, smiled like water breaking in the moonlight, and lunged silently into his arms. She almost knocked him off his feet—Julie was a strong woman and quite as tall as Farrell—and that was entirely proper, that was the only tradition they had ever had time to establish, unless you counted their habit of meeting one another in strange places, always unprepared. Farrell had thought often in the last ten years—though never when he was with her—that, of all the generous things that had happened to him with women, those first thundering embraces from Julie Tanikawa, after a suitable separation, were about the best. Taking everything into consideration, like the fact that we can’t stand each other longer than three days.

“I was just thinking about you,” she said. She leaned back against his arms, resting her own arms stiffly on his shoulders. Farrell nodded smugly. “Of course you were. That’s because I called you here. You weren’t even in Avicenna until maybe five minutes ago.”

Julie raised one eyebrow, and Farrell recalled a long, tipsily innocent spring night she had spent in trying to teach him to do that. “Well, somebody’s been feeding a cat on Brendan Way for the last two years.” Farrell began an indignant growl, but she interrupted him calmly. “I’m no good about letters, you know that. Anyway, I knew you’d show sooner or later. One of us always conjures up the other.”

He stood peering at her, frowning with the effort of relearning her face, as students ambled by, pushing bicycles and laughing through sandwiches. A dishy, merry, barn-owl face, every feature too large for conventional Western beauty, except the nose, which was too small. But her skin remained as clear and translucent as white wine, and the bones beneath were, at thirty, beginning to keep their old promise of pride and steadfastness. Her face has secrets now, like Ben’s face. I wonder if mine does. Aloud he said, “Nothing changes. You still look like an Eskimo.”

“You still haven’t seen one.” He realized that he had never held her this long before; usually, no matter how joyous the welcome, they let go quickly and stepped away, a single precise pace. This time, both of them trusted their full weight to the strength of the awkward clasp, leaning apart but keeping firm hold. They might have been children playing a street game, swinging each other inside a circle chalked on the sidewalk.

“You didn’t marry old what’s-his-face,” he said. “Alain, the archaeologist.”

Julie giggled. “He was a paleoethnologist. Still is, I guess, back in Geneva. No, I didn’t marry him. Almost, though.”

“I liked him.” Farrell said.

“Oh, he liked you,” Julie said. “They always do. You’re such a nice fellow. They think you’re not a threat, and you know they’re not.”

A couple of fraternity boys were shouting at them from a second-floor window, “Action! We want some action down there!” The night faces were coming on duty now, floating down toward Parnell like Portuguese men-of-war. Pierce/Harlow hurried by—Farrell would have sworn it was Pierce/Harlow—leading two Dobermans; and a woman lugging a huge signboard that likened a local judge, in four colors, to the Horned Beast of the Apocalypse, banged it savagely against Julie’s legs to get past. And still they stood within their invisible circle, both gaping absurdly in growing bewilderment. One of them was shaking, but Farrell could not tell which one.

“That record you were going to make,” she said, “with Abe and that crazy drummer. Danny.”

“It didn’t work out.” Their voices were becoming steadily softer, cracking thinly.

“I looked for it.” A monk shoved a lighted stick of incense between Julie’s fingers, and then asked her in a Bronx accent for a few pennies for Krishna. Farrell heard himself say wonderingly, “Let’s go home.”

Julie did not answer him. Farrell put his hand on the back of her neck. For a moment she closed her eyes and sighed like a child falling asleep; then, as the hooting from the fraternity house redoubled, she turned in his arms, saying angrily, “No, no, damn, that’s absolutely all I need.” Farrell began to speak, but she pulled his hand away, brushing it gently across her cheek before she let it go. She said, “No, Joe, I don’t think so. It would be sweet and happy, but we’d better not.”

“It’s time, Jewel. It’s exactly time, this minute.”

She nodded, still not quite looking at him. “But sometimes you let things go by, even when it’s time. Because you don’t know what you’ll be afterward.”

“Hungry,” Farrell said. “I’ll cook dinner. I’ve never cooked for you.” Two young men wearing mime-white face and Danskins passed them, talking about crampons, carabiners, and prusicking. Across the street, a candidate for something gave a printed flyer to a person dressed as a huge parrot. Julie said, “Joe, damn it, I’m going shopping, I have to pick up some drawing supplies, they close in twenty minutes.”

Farrell sighed and lowered his arms, taking a step backward. “Well,” he said. “Maybe it’s not time.” She looked straight at him then, but he could not tell whether she felt regret, annoyed embarrassment, or a relief as sour and jumbled as his own. He put his hands in this pockets. “Anyway, it’s wonderful to see you,” he said. “Look, I’m staying up on Scotia with a couple of friends. It’s in the book, Sioris, it’s the only one there is. Call me. Will you call me?”

“I will,” Julie said, so softly that Farrell had to read her lips to make out the words. He kept backing away, knowing—even without the whistles and guffaws of the fraternity boys—that he looked ludicrously as if he were withdrawing from the presence of royalty. But he knew also that she would not call, and it seemed to him that he had once again stumbled across something irreplaceable just at the moment of its extinction. He said, “Check the clutch on that monster, Jewel. It might be slipping a little.”

He was striding briskly toward Parnell, shoulders only a little hunched, when she said, “Farrell, come back here,” loudly enough that a baying chorus immediately took it up: “Farrell, you get back there this minute!… You heard her, Farrell!” When he turned, he saw her beckoning forcefully, ignoring the second-floor gallery. He approached her with some hesitation, wary of old of the half smile playing like a kitten with one corner of her mouth. The last time he had seen that particular smile, they had both been in a Malaga jail fairly shortly thereafter.

“Get on,” she said. She pushed the BSA off the kickstand and straddled it, waiting for him. When he only stared, oblivious to highly detailed instructi

ons from their audience, she repeated the command sharply without looking back as she tugged her helmet on.

“Shopping,” Farrell said. “What happened to shopping?” Julie started the engine, and the air around the BSA danced to life, this time enclosing them within a roaring privacy—a momentary country, trembling at the curb. Outside, beyond their borders, the honey-slow twilight was thinning and quickening to a cold, dusty lavender. Skateboarders hurtled past like moths, urgently contorted, one-dimensional in the pale headlights rushing up the hill toward them. Farrell sat down behind Julie again.

“Where are we going?” he asked. The street was beginning to swirl around them, as certain protective inscriptions will do when the magic has been spoken right. Julie turned to face him and stood her stick of incense upright in his hair. “Let’s wait and see where the bike wants to go,” she said. “You know I never argue with my bikes.”

Chapter 5

My,” he said, “what kind of motorcycle is a Tanikawa?”

“A dirt bike. Don’t move, stay with me.” She was propped on his chest, looking at him, her smile lifting as delicately as the corners of her eyes. The pupils were narrowing to normal size again. Farrell said, “You smell so good. I can’t believe your smell.”

Julie kissed his nose. She said, “Joe, you’re thin. I never imagined you’d be so thin.”

“Coyotes are thin. That’s my totem, the coyote.” He put a hand up to touch her cheek, and she let her head rest on it. “I never imagined you imagining me like that. Hussy.”

“Oh, you try people on,” Julie said. “Didn’t you ever wonder about me at all? As much as you wonder?” Now she lowered herself against him, her face cool on his throat, her body surrounding him like water. But when he said nothing, she dug her chin into him and pulled his hair. “Come on, Joe, it’s been ten years, eleven years now. I want to know.”

“I thought about you,” he said quietly. “Mostly wondering where you were, how you were doing.” He caught her hands this time. “I didn’t want to have fantasies, Jewel. You try strangers on like that, friends not so much.”

“But we were always both,” she said. “Or neither. Run into each other every couple of years, pal around for a few days until we fight. That’s not friendship, that’s just nothing. Scratch my back.”

Farrell scratched. “Well, it keeps me hopeful, whatever it is. Even if I’m stranded in Bonn, or Albany, there’s always that chance—turn one more corner and here comes Julie. New job, new language, new clothes, new man, new bike.” He drew his fingernails up and down her hips, shivering with her. “Hell, you’re my role model, I’ve been imitating you for years.”

“And you say you didn’t fantasize.” She slid off him and pulled the coverlet over them, lying on her side with her legs drawn up, and looking suddenly homely and frail. Farrell tried to draw her close again, but her knees held him away.

“Yeah, all my men,” she said. “And you were great buddies with all of them, and you weren’t ever jealous, not once. Never watched me going home with Alain or Larry or Tetsu and thought about me being like this with them, lying and talking—”

“Larry who? Which one was Larry?”

“The lieutenant in Evreux. At the airbase. You used to play chess with him all the time. Joe, I think you’re the biggest hypocrite I’ve ever known. I mean that.”

Farrell lay back, looking around at the room. He had no sense yet of being in Julie’s home with her; it still felt very much as if they had fumbled drunkenly at the first door they came to, found it open, and fallen upon each other in a little free space granted them by an anonymous donor. But now, in the oval of light that the big bed-lamp threw, he began to recognize objects that he had seen with Julie in Evreux and Paris, in Minorca and Pittsburgh and Zagreb. The three rows of copper-bottomed pots, the painting her sister did of her in high school, the stones and seashells she always has around everywhere; the brown, blood-cracked cape that wheezy old fraud of a bullfighter gave her in Oaxaca. Same red chenille bedspread, same stuffed giraffe, same ankle-munching coffee table she bought at a Seattle garage sale. Julie’s a collector. I used to think she traveled light, but it’s that men carry things for her and ship them for nothing. All the same, a sudden spill of half-sorrowful tenderness and comradeship for Julie’s friendly belongings made him shiver and take hold of her hair.

“Why did you call me back?” he asked. “I was walking off just sure I’d messed everything up forever.”

“Maybe you have, I don’t know yet. I wanted to find out what there was to mess up.” She shrugged herself deeper under the covers. “Besides, it was time, you were right about that. One way or the other, we couldn’t go back to being whatever we were. Kittens.”

“Are you glad?” Julie closed her eyes. Farrell licked a sweaty place just below the nape of her neck. He said, “You taste like red clover. Little tiny explosions of honey.”

Julie put her hand on his stomach, just below the ribs. “Thin,” she murmured; and then, “Joe? Do you remember the time we met in Paris when I was in my car?”

“Mmm. I was dragging along Monsieur-he-Prince. You were just sitting there at the curb.”

“I was supposed to take twenty airmen on a tour the next day and I’d forgotten all about it and I hadn’t made any arrangements at all. So I was sitting and thinking about that. Then I saw you. You looked like hell.”

“Felt like hell. That was my bad winter. I’ve never been that down again or in that much trouble. Not at the same time, anyway. Sitting in your car with you, that was the warmest I’d been since I got to France.”

She patted him, still keeping her eyes closed. “Poor Joe, in your New York topcoat.” A large, fluffy, white cat jumped up on the bed and wedged himself inflexibly between them, jacking up his rear and purring like a sewing machine. “This is Mushy,” Julie said. “Old slobby Musheroo. He started out to be Mouche, but it didn’t take. Did it, you fat fiend?” The cat kneaded her arm, but he eyed Farrell.

“You’ve never had a cat,” Farrell said. “I don’t remember you ever having pets at all.”

“Mushy isn’t really mine. He came with the house, sort of.” Her eyes opened a few inches from his own—neither brown nor quite black, but a questioning, elusive darkness that he associated with no one else. “Do you remember that I was counting?”

“What?” he said. “What counting?”

“In the car, writing on the window. One, two, three, four, like that. Remember?”

“No. I mean, I do now, because you tell me, but not really. Move that cat and come see me.”

Julie reached up suddenly and switched off the bed-lamp. Farrell’s retinas, long accustomed to hurry calls, did the best they could, filing away the high contrast of black hair slashing across a shoulder the color of weak tea, the small breast drawn almost flat by her movement, and the shadow of tendons in her armpit. He reached for her.

“Wait,” she said. “Listen, I have to tell you this in the dark. I was counting me. Counting my cycle. I was trying to figure if it would be safe for me to take you back to my room with me. You looked so bad.”

The white cat had fallen asleep, but he was still purring with each breath. There was no other sound in the room. Julie said, “It was a matter of a day, one way or the other. I remember that very clearly. You don’t remember anything?”

The lights of a car slid over the far wall and part of the ceiling of Farrell’s hotel room, making the bidet glow like a pearl and turning the half-empty suitcase at the foot of the bed into a raw grave. Beside him, across the snowdrift of the cat—Paris winters are dirty, the air gets sticky and old—Julie’s round, tumbly-soft Eskimo face came and went again, as Julie herself came and went up and down in the world; as he would learn to come and go lightly too, if he didn’t die, if he made it through this long, dirty winter. He said, “I was twenty-one years old, what did I know?”

For a moment he could not feel Julie’s breath on his face. Then she said, “I just told you that to show y

ou that I did think about you, even that long ago.”

“That’s nice,” he said, “but I wish you hadn’t told me. I don’t remember a damn thing about the counting, or whatever, but I remember that winter. I think you could probably have changed the course of world history by taking me home with you. All that dumb misery would have had to go somewhere.”

“Aw,” she said. “Aw, poor topcoat.” She picked up the cat and poured him gently off the bed. “Well, come here right away,” she said. “This is for then. Officially. Old friend. Old something. This is for then.”

In the morning he woke in bed with a suit of armor. Actually it was chain mail, slumped empty next to him like the gleaming husk of some steel spider’s victim; but the great helm that shared his pillow dominated his waking completely. The helm looked like a large black wastebasket with the bottom reinforced by metal struts and with most of one side cut away and covered by a slotted steel plate, riveted in place. Farrell had his arm over it, and his nose pressed into the face plate—it was the cold, rough, painty smell that had awakened him. He blinked at the helm several times, rubbed his nose, then rolled onto one elbow, looking around for Julie.

She was standing in the doorway, dressed and laughing silently, fingers at her lips in one of the few echoes of classical Japanese manners that he had ever noticed in her. “I wanted to see what you’d do,” she gasped. “You were so sweet to it. Were you scared?”

Farrell sat up, feeling grumpy and ill-used. “Should see some of the artifacts I’ve waked up with, the last ten years.” He lifted a fold of the mail shirt, finding it surprisingly fluid for all its weight. “All right, I’ll say it. What the hell is this?”

Julie came and sat on the bed. She smelled of the shower and of sunlight, and there was still a fuzzy bloom of water on her hair. “Well, this is a hauberk and this is the camail, to guard your throat, and these are for your legs, the chauses. It’s a complete suit, except for the gauntlets and the arming coat, the padding. And the surcoat. Most people generally wear some kind of surcoat over their mail.”

The Unicorn Anthology.indb

The Unicorn Anthology.indb Sleight of Hand

Sleight of Hand Return

Return The Last Unicorn

The Last Unicorn Two Hearts

Two Hearts Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

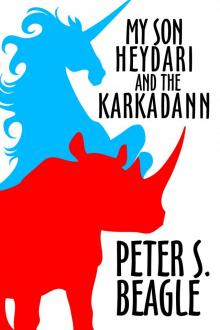

Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle My Son Heydari and the Karkadann

My Son Heydari and the Karkadann The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories

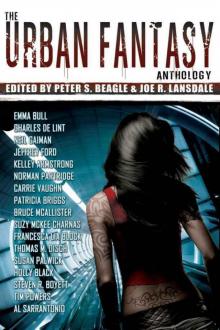

The Magician of Karakosk, and Other Stories The Urban Fantasy Anthology

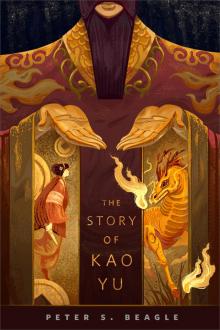

The Urban Fantasy Anthology The Story of Kao Yu

The Story of Kao Yu The Karkadann Triangle

The Karkadann Triangle My Son and the Karkadann

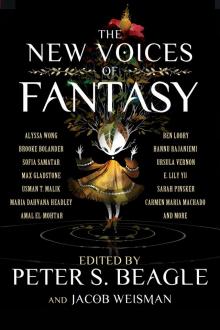

My Son and the Karkadann The New Voices of Fantasy

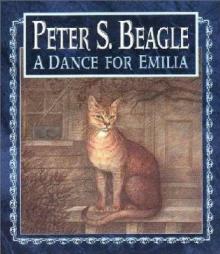

The New Voices of Fantasy A Dance for Emilia

A Dance for Emilia We Never Talk About My Brother

We Never Talk About My Brother The Folk Of The Air

The Folk Of The Air The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World

The Magician of Karakosk: Tales from the Innkeeper's World A Fine and Private Place

A Fine and Private Place Lila The Werewolf

Lila The Werewolf Tamsin

Tamsin Innkeeper's Song

Innkeeper's Song